History of Photography

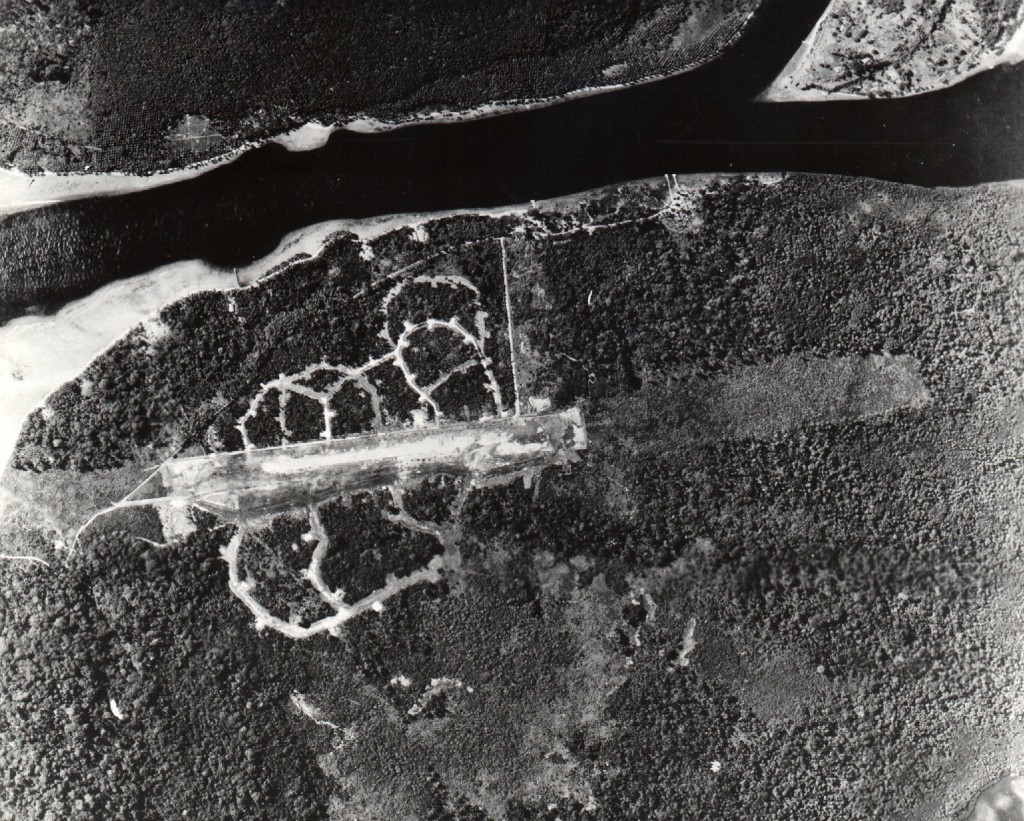

The Most Honored Photograph

- Photograph in public domain, this copy from Naval Aviation Museum

Doesn’t look like much, does it? But, depending upon your definition, this photograph, a team effort by 9 men, is the most honored picture in U. S. History. If you want to find out about it, read on. It’s an interesting tale about how people sometimes rise beyond all expectations. It takes place in the early days of World War II, in the South Pacific, and if you’re a World War II history buff, you may already know about it.

The Screwed Up Pilot

First, let’s get this out of the way. Jay Zeamer wasn’t a photographer by trade. He was mostly a wanna-be pilot. He looked good on paper, having graduated with a degree in civil engineering from MIT, joining the Army Air Corps, and receiving his wings in March, 1941. He was a B-26 bomber co-pilot when World War II started.

His classmates all rapidly became lead pilots and squadron leaders, but not Jay. He couldn’t pass the pilot check tests despite trying numerous times. He was a good pilot, but just couldn’t seem to land the B-26. Landing, from what I’ve read, was considered one of the more important qualifications for a pilot. Stuck as a co-pilot while his classmates and then those from the classes behind him were promoted, he got bored and lost all motivation.

Things came to a head when co-pilot Zeamer fell asleep while his plane was in flight. Not just in flight, but in flight through heavy anti-aircraft fire during a bombing run. He only woke when the pilot beat him on the chest because he needed help. His squadron commander had him transferred to a B-17 squadron in Port Moresby, New Guinea where he was allowed to fly as a fill-in navigator and occasionally as a co-pilot. He was well liked and popular — on the ground. But no one wanted to fly with him.

Zeamer finally managed to get into the pilot’s seat by volunteering for a photoreconnaissance mission when the scheduled pilot became ill. The mission, an extremely dangerous one over the Japanese stronghold at Rabual, won Zeamer a Silver Star — despite the fact that he still hadn’t qualified to pilot a B-17.

The Eager Beavers

Zeamer become the Operations Officer (a ground position) at the 43rd Air Group. Despite his lack of qualification, he still managed to fly as a B-17 fill-in pilot fairly often. He had discovered that he loved to fly B-17s on photoreconnaissance missions, and he wanted to do it full-time. There were only three things standing in his way: he didn’t have a crew, he didn’t have an airplane, and oh, yeah, he still wasn’t a qualified pilot.

He solved the first problem by gravitating to every misfit and ne’er-do-well in the 43rd Air Group. As another pilot, Walt Krell, recalled, “He recruited a crew of renegades and screwoffs. They were the worst — men nobody else wanted. But they gravitated toward one another and made a hell of a team.”

The plane came later. An old, beat-up B-17, serial number 41-2666, that had seen better days was flown into their field to be scavenged for spare parts. Captain Zeamer had other ideas. He and his crew decided to rebuild the plane in their spare time since they weren’t going to get to fly any other way. Exactly how they managed to accomplish their task is the subject of some debate. Remember, there were so few spare parts available that their ‘plane’ was actually brought in originally to be a parts donor.

But rebuild it they did. Once it was in flying shape the base commander congratulated them and said he’d find a new crew to fly it. Not surprisingly, Zeamer and his crew took exception to this idea, and according Walt Krell the crew slept in their airplane, having loudly announced that the 50 caliber machine guns were kept loaded in case anyone came around to ‘borrow’ it. There was a severe shortage of planes, so the base commander ignored the mutiny and let the crew fly – but generally expected them to take on missions that no one else wanted.

The misfit crew thrived on it. They hung around the base operations center, volunteering for every mission no one else wanted. That earned them the nickname The Eager Beavers, and their patched up B-17 was called Old 666.

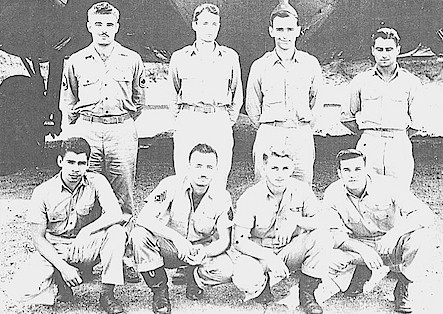

- The Eager Beavers:(Back Row) Bud Thues, Zeamer, Hank Dominski, Sarnoski (Front Row) Vaughn, Kendrick, Able, Pugh. http://www.homeofheroes.com/wings/part2/07_zeamer_sarnoski.html

Once they started flying their plane on difficult photoreconnaissance missions, they made some modifications. Even among the men of a combat air station, the Eager Beavers became known as gun nuts. They replaced all of the light 30 caliber machine guns in the plane with heavier 50 caliber weapons. Then the 50 caliber machine guns were replaced with double 50 caliber guns. Zeamer had another pair of machine guns mounted to the front of the plane so he could remotely fire them like a fighter pilot. And the crew kept extra machine guns stored in the plane, just in case one of their other guns jammed or malfunctioned.

As odd as all this sounds, the South Pacific theatre in the early days of World War II was a chaotic area scattered over thousands of miles with very little equipment. Having a plane with an apparently nutty crew who volunteered for every awful mission not surprisingly made the commanding officers look the other way.

Buka

In June, 1943, the U. S. had secured Guadalcanal in the southern Solomon Islands. They knew the Japanese had a huge base at Rabaul, but were certain there were other airfields being built in the Northern Solomon Islands. They asked for a volunteer crew to take photographs of Bougainville Island to plan for an eventual invasion, and of Buka airfield on the north side of the island to assess for increased activity there. It was considered a near-suicide mission — flying hundreds of miles over enemy airspace in a single, slow bomber. Not to mention photoreconnaissance meant staying in level flight and taking no evasive action even if they were attacked.

- Credit: World Factbook

The only crew that volunteered, of course, was Jay Zeamer and the Eager Beavers. One of the crew, bombardier Joseph Sarnoski, had absolutely no reason to volunteer. He’d already been in combat for 18 months and was scheduled to go home in 3 days. Being a photo mission, there was no need for a bombardier. But if his friends were going, he wanted to go, and one of the bombardier’s battle stations was to man the forward machine guns. They might need him, so he went.

They suspected the airstrip at Buka had been expanded and reinforced, but weren’t sure until they got close. As soon as the airfield came in sight, they saw numerous fighters taking off and heading their way. The logical thing to do would have been to turn right and head for home. They would be able to tell the intelligence officers about the increased number of planes at Buka even if they didn’t get photos.

But Zeamer and photographer William Kendrick knew that photos would be invaluable for subsequent planes attacking the base, and for Marines who were planning to invade the island later. Zeamer held the plane level (tilting the wings even one degree at that altitude could put the photograph half a mile off target) and Kendrick took his photos, which gave plenty of time for over 20 enemy fighters to get up to the altitude Old 666 was flying at.

The fighter group, commanded by Chief Petty Officer Yoshio Ooki, was experienced and professional. They carefully set up their attack, forming a semi-circle all around the B-17 and then attacking from all directions at once. Ooki didn’t know about the extra weapons the Eager Beavers had mounted to their plane, but it wouldn’t matter if he had; there was no way for a single B-17 to survive those odds.

During the first fighter pass the plane was hit by hundreds of machine gun bullets and cannon shells. Five crewman of the B-17 were wounded and the plane badly damaged. All of the wounded men stayed at their stations and were still firing when the fighters came in for a second pass, which caused just as much damage as the first. Hydraulic cables were cut, holes the size of footballs appeared in the wings, and the front plexiglas canopy of the plane was shattered.

Zeamer was wounded during the second fighter pass, but kept the plane flying level and took no evasive action until Kendrick called over the intercom that the photography was completed. Only then did he begin to move the plane from side-t0-side allowing his gunners better shots, just as the fighters came in for a third wave of attacks. The third pass blew out the oxygen system of the plane, which was flying at 28,000 feet. Despite the obvious structural damage Zeamer put the plane in an emergency dive to get down to a level where there was enough oxygen for them men to survive.

During the dive, a 20mm cannon shell exploded in the navigator’s compartment. Sarnoski, who was already wounded, was blown out of his compartment and landed on a catwalk beneath the cockpit. Another crewman reached him and saw there was a huge wound in his side. Despite his obviously mortal wound, Sarnoski said, “Don’t worry about me, I’m all right” and crawled back to his gun which was now exposed to 300 mile an hour winds since the plexiglass front of the plane was now gone. He shot down one more fighter before he died a minute or two later.

The battle continued for over 40 minutes. The Eager Beavers shot down several fighters and badly damaged several others. The B-17 was so heavily damaged, however, that they didn’t expect to make the several hundred miles long flight back home. Sarnoski had already died from his wounds. Zeamer had continued piloting the plane despite multiple wounds. Five other men were seriously wounded.

Flight Officer Ooki’s squadron returned to Buka out of ammunition and fuel. They understandably reported the B-17 was destroyed and about to crash in the ocean when they last saw it.

The B-17 didn’t quite crash, though. Zeamer had lost consciousness from loss of blood, but regained it when he was removed from the pilot seat and lay on the floor of the plane. The copilot, Lt. Britton, was the most qualified to care for the wounded and was needed in the back of the plane. One of the gunners, Sergeant Able, had liked to sit in the cockpit behind the pilots and watch them fly. That made him the most qualified of the crewman, so he flew the plane with Zeamer advising him from the floor while Britton cared for the wounded.

The plane made it back to base. (Britton did return to the cockpit for the landing.) After the landing, the medical triage team had Zeamer removed from the plane last, because they considered his wounds mortal. Amazingly, the one thing on the plane not damaged was the cameras. The photos in them were considered invaluable in planning the invasion of Bougainville.

Epilogue

All of the wounded men recovered, although it was a close thing for Captain Zeamer. In fact, a death notification was sent to his parents somewhat prematurely. He spent the next year in hospitals recovering from his wounds, but lived a long and happy life, passing away at age 88.

Both Zeamer and Sarnoski were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for the mission, the only time in World War II that two men from one plane ever received America’s highest medal for valor in combat. The other members of the crew were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor as an award for bravery.

So, somewhat surprisingly, the most decorated combat flight in U. S. history didn’t take place in a major battle. It was the flight of Old 666.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

October, 2013

REFERENCES:

Caidin, Martin: B17: The Flying Forts. 1968.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jay_Zeamer,_Jr.

http://jhnwriter.wordpress.com/2011/02/18/jay-zeamer-pilot-of-the-old-666-who-flew-straight/

The Greatest Air Battle of World War II

Authors note: This is inspired by, and dedicated to, all the photographers and videographers who have (and still do) put themselves in harm’s way to get the shot.

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Andrew W Hall

-

Clint Hayes

-

Mike

-

Clint

-

Dave Armstrong

-

Brad

-

Tim R

-

Kevin Purcell

-

Bill Harshaw

-

Tuan

-

David Shell

-

David Shell

-

Matt

-

Fletch

-

Nqina Dlamini

-

Dummey

-

NancyP

-

Kevin Purcell

-

Bob

-

Raimo K

-

miejoe

-

Alan Fairley

-

Tom Alicoate

-

intrnst

-

Brian Chambers

-

Eric Larsen