Equipment

Six Future Techs We Hope to See Become the Industry Standard in Photography and Videography

With WPPI, NAB, and the dozen other photo and videography shows going on over the last few months, we’ve been busy engulfed in new cameras, new technology, and new workflows for the coming year and beyond. We’ve certainly done our fair share of coverage on these shows, and we’ll know more when the products are actually released and tested. But the excitement got us thinking, what are some of the tech teased in recent years that we hope to see implemented into the standard? Various brands are all releasing their densely developed concepts, and we decided we wanted to take a moment and discuss the most innovative, and what we hope to see become a standard in the industry.

While the obvious always stands true. Everyone wants faster frame rates, more focus points, better dynamic range and longer battery life. So we’re using this as an opportunity to spotlight the tools that have been shown off but are different from the usual requests we want out of camera systems.

Canon 5d Mark IV’s Dual-Pixel RAW [photo]

At the launch of the Canon 5d Mark IV, they teased a focusing tool that teetered on the gimmicks put out by Lytro, where you could adjust focusing after the shot, making sure all of your photos are always in focus. The technology, admittedly, fell flat. Its failure was the result of no one really implementing it, on the software side. Still, at the time of writing this piece, the only way to take advantage of this technology is to use Canon’s awful imaging software. Those who are working with Photoshop, Lightroom or Capture One aren’t able to play with this tool, which was never fully adapted.

How it works is simple. It works by taking two photos using the right and left half of a single pixel, then filters out the information. Since this is capturing different data from each half of the pixel, such as flare, and sharpness, and then allows you to adjust them accordingly, while still maintaining the 30MP image size. The adjustments of this tool are admittingly subtle but could help considerably when you’ve taken a fantastic shot, only to see your subject is ever so slightly out of focus. While this isn’t as in-depth or as impressive at the Lytro Cameras from years past, it does have a practical purpose that we’d like to see implemented further.

Electronic Shutter of the Canon 1D [photo]

While not new tech, the original Canon 1D had an impressive piece of technology in it, that was quickly abandoned. And that technology was known as the electronic shutter. Whereas most cameras use a series of shutter blades to expose the sensor to light, the original Canon 1D did it by shutting off the electricity to the sensor, when exposing the sensor. It still had a mechanical shutter, but it was only used in the readout process. All of this was achieved because the Canon 1D used a CCD sensor, as opposed to the CMOS sensors typically found on modern systems. While as of right now, it seems impossible to get the same type of technology in a CMOS sensor, but we’d love to see developments to be made to give us the electronic shutter in a CMOS system.

A visualization of how your traditional shutter works, and why your flash sync speed has a maximum theoretical speed.

So what makes this special? For one, general reliability. The Canon 1D, through the use of an electronic shutter, had a shutter actuation rated for around 500K, nearly four times what most cameras promise. Secondly, for flash sync speed. Most cameras allow sync speeds anywhere from 1/160th of a second to 1/250th, where the Canon 1D had a flash sync speed of 1/500th of a second. This was because most cameras sync speeds are dependent on how quickly the shutter can fully open, trigger the light, and the begin the closing process. The theoretical limit to this is at 1/200th of a second for a full frame sensor and 1/250th on a crop sensor. Additionally, the Canon 1D allowed for shutter speeds as high as 1/16,000 of a second. Impractical, maybe, but impressive? Definitely. Of the technologies mentioned in this piece, this one seems likely to make a comeback, with it being shown off in many of the Fujifilm systems, such as the FujiFilm X-T1.

Pixel Shift Technology [photo]

Technology originally developed for the Pentax K-1, pixel shift technology is finally making its rounds to the mainstream, with it most notably being introduced to the Hasselblad H5D-200c MS and the Sony a7RIII. What pixel shifting does is essentially take multiple frames, with the sensor shifting a pixel with each shot. This allows for up to 4 times the resolutions and sharpness in your photos.

Multiple RAW Sizes [photo]

At this point, I expect to get some criticisms that I’m a Canon fanboy, though I certainly have my list of complaints with their platform. But there is one thing that they do right, that virtually no other brand does; multiple Raw sizes. What has seemingly been on Canon systems forever now (seriously, I had cameras ten years ago with this functionality), it’s still lacking on both the Nikon and Sony systems. Traditionally, Canon DSLRs are equipped with multiple Raw formats – sRaw, which is about 1/3rd the resolution of full Raw, mRaw, at around 2/3rds the resolution and Raw, which is, of course, the full file size.

So why is this useful? Well simply because you generally don’t need a full resolution all the time. With camera systems pushing 50mp, it’s rare that you actually need that resolution for every scenario. By implementing a smaller resolution, you’re able to create a faster workflow, save card and hard drive space, and churn out the images to your client faster. The image size I’d need for a 2-page advertising campaign is not the same resolution needed for my nephews birthday party, the having the ability to adjust the resolution as you shoot is a huge advantage, and it’s surprising to not see it on other platforms.

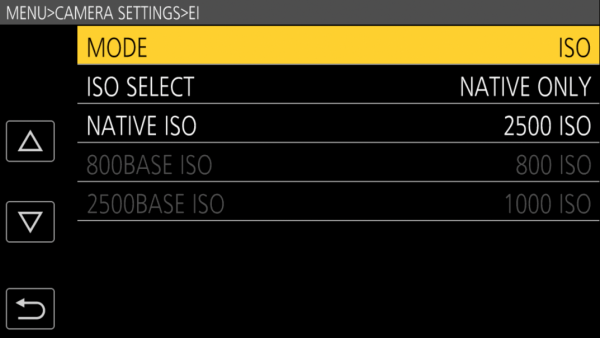

Dual Native ISO

Typically, a video camera has a single native ISO at which the sensor performs at its best. Cranking the ISO higher than the native setting will introduce more camera noise, and lowering the ISO below the native setting affects dynamic range. Cameras with dual native ISOs have two analog circuits per photo site, enabling an equal signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range at two different ISO levels. Panasonic debuted this technology back in 2014 with the Varicam 35. Since then, it’s also been a feature of their Varicam LT, EVA-1, and GH5S. Recently, we’ve also seen other manufacturers adopt this design. RED’s new 5K Gemini sensor has dual native ISOs of 800 and 3200, and Blackmagic’s upcoming 4K pocket camera has dual native ISOs of 400 and 2500.

The flexibility afforded by dual native ISOs makes these cameras much more attractive to customers who frequently have to work in low-light fields such as documentary, news, weddings, or basically anything that isn’t a traditional studio shoot. Based on the popularity and quick adoption of this feature, we wouldn’t be surprised if it’s as common as internal ND filters in the next five years or so.

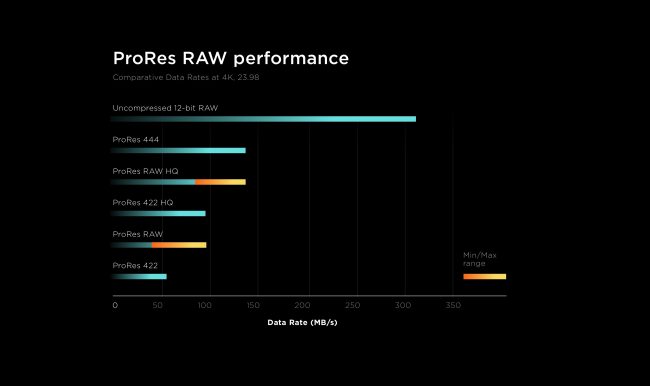

ProRes RAW

A joint venture between Apple and Atomos, ProRes RAW is being advertised as “The flexibility of RAW, with the simplicity of ProRes.” I don’t have the page space to talk about it in too much detail (you can read Apple’s white paper if you’re especially interested), the whole idea basically boils down to a compressed RAW format that puts off debayering until post-production. Since uncompressed RAW data rates are so high, and RAW transcoding is so processor-intensive, the RAW workflow isn’t really an option for shooters without exceptionally deep pockets and forgiving deadlines. ProRes RAW, on the other hand, takes up far less drive space than uncompressed RAW and should play back reliably on most recent computers, at least in applications that support it. While some manufacturers, like RED and Blackmagic, have introduced compressed RAW recording, but those are still proprietary formats limited to in-camera recording. Atomos and Apple are hoping that ProRes RAW becomes an industry-standard solution for external recording.

This is very promising technology that unfortunately has a good chance of being ruined by video industry infighting. If things go well, we could see ProRes RAW become an open format that allows more people to reap the benefits of a RAW workflow. If things go poorly, we could see Apple and Atomos close walls around the format and force out customers who aren’t a part of their specific ecosystems. Currently, Final Cut Pro X is the only NLE that supports ProRes RAW and Atomos recorders are the only ones that will record it. Here’s hoping that changes soon.

Certainly, with the various brands, we’ve missed an interesting piece of technology in the mix. Have something you think is worth talking about? Feel free to share your thoughts and opinions below in the comments.

Zach Sutton & Ryan Hill

Author: Zach Sutton

I’m Zach and I’m the editor and a frequent writer here at Lensrentals.com. I’m also a commercial beauty photographer in Los Angeles, CA, and offer educational workshops on photography and lighting all over North America.

-

Gosh1

-

Y.A.

-

DrJon

-

Phanter

-

Phanter

-

Steven Wray

-

Athanasius Kirchner

-

Fritz Rutz

-

Athanasius Kirchner

-

baron

-

baron

-

T N Args

-

Ryan Hill

-

Nemo Niemann

-

Fritz Rutz

-

T N Args

-

CheshireCat

-

Ryan Hill

-

David Bateman

-

mohammad mehrzad

-

CheshireCat

-

Paul Trantow

-

grubernd

-

Franck Mée

-

mohammad mehrzad

-

TinusVerdino

-

Miguel Ángel Roldán

-

Miguel Ángel Roldán

-

DrJon

-

Franck Mée