Geek Articles

Stopping Down Some Bargain Primes and Zooms

In my last post, we looked at how the field curvature of some really excellent 35mm f/1.4 primes affected what happens when we stop down the lens. The takeaway message is that as you stop down, things change a bit differently with the different lenses, but by f/5.6 they were similar. Still slightly different, but pretty similar.

The real purpose of these articles though, was to look at generalization that is often made; ‘all lenses are the same at f/8’. These days f/8 generally means you’re starting to get diffraction softening. That’s not a bad thing and it’s reasonably easy to overcome in post, but it does tend to level the playing field, since diffraction softening don’t care what lens you use.

I thought we should compare a couple of reasonably priced, but pretty good 35mm lenses for the next step. If you’re shooting stopped down, is there any reason to spend the big bucks on an f/1.4 lens? And for those people who still like to say things about ‘this zoom is as good as a prime’ I thought we’d look at a couple of good 24-70mm f2.8 zooms at 35mm for the same reason.

I will mention that you probably should read the last post, since I’m not going to repeat any background on what these MTF vs Field vs Focus plots (AKA field curvature plots) are in this article.

Smaller 35mm Primes

Let’s look at two very popular 35mm lenses; the Canon 35mm f/2 IS and the Tamron 35mm f1.8 SP Di VC. These are both really excellent lenses that, if you don’t need an f/1.4 aperture, offer an excellent alternative to the bigger, more expensive lenses and as a bonus have image stabilization which most f/1.4 primes don’t offer.

Just for a reference, I’m going to repost the graphs of the Tamron 35mm f1.4 SP from the previous article. Notice it starts off with pretty good side-to-side sharpness, although the sagittal and tangential fields are of different shape, so they don’t quite overlap. As it stops down it gets sharper and the increased depth of field results in better overlap.

Lensrentals.com, 2019

By f/5.6 it is maximally sharp, although there is some area in the tangential field that’s not quite as sharp as the center. If we average the tangential and sagittal fields, we see at f/5.6 it’s not perfectly sharp edge-to-edge, but it’s close enough for any reasonable purpose.

Lensrentals.com, 2019

Now let’s compare it to the smaller 35mm primes to see how they stack up. Since we stopped the f/1.4 lenses to f/5.6, it seems fair that we stop these down through f/8.

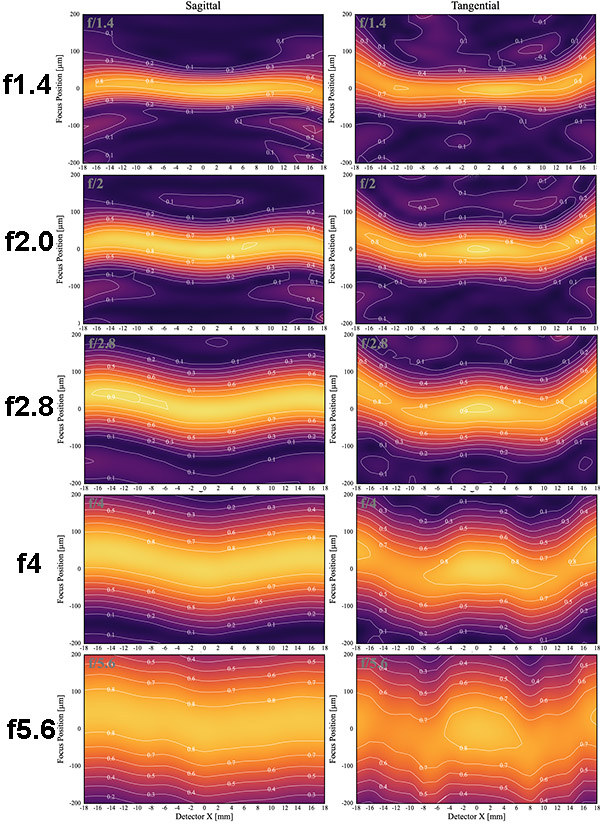

Canon 35mm f/2.0 IS

At f/2, it’s apparent the Canon isn’t as sharp away from center as the f/1.4 lenses were at f/1.4.

Lensrentals.com, 2018

As we stop down, it becomes apparent that the sagittal field curvature is more pronounced with this lens, too. Still, by f/5.6 and f/8 we can see that the lens is getting good side-to-side sharpness although it looks like the fields still don’t quite overlap.

If we look at the f/8 average, though, things look pretty good. The edges are nearly as good as the Tamron was at f/5.6, although there’s a bit more field curvature. You could pixel-peep the difference and see the Tamron at f/5.6 was a bit better away from the center than the Canon at f/8, but it would take a lot of effort.

Lensrentals.com, 2019

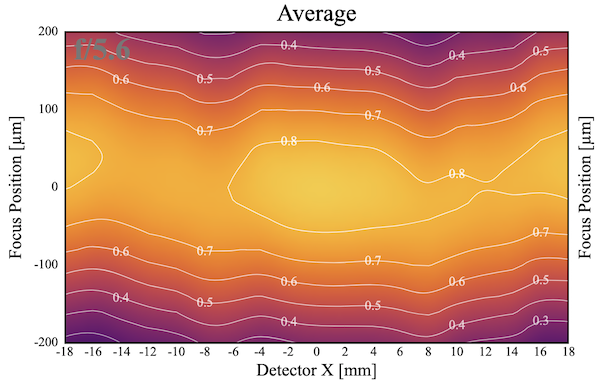

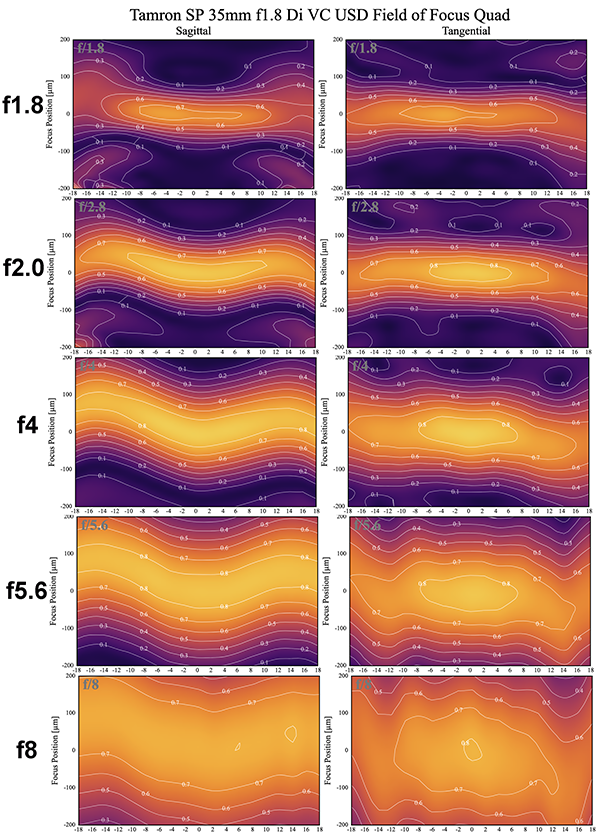

Tamron 35mm f/1.8 SP VC

As with the Canon, the Tamron isn’t as sharp wide open as the more expensive lenses were at f/1.4.

Lensrentals.com, 2019

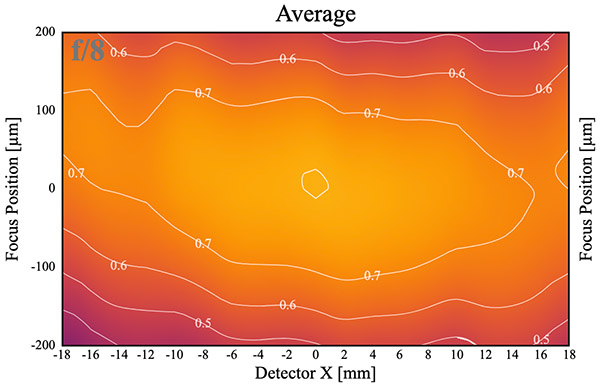

While the sagittal field curvature isn’t as pronounced as the Canon was, the tangential plane doesn’t sharpen up quite as well as the Canon. At f/8 our overall field, though, is still pretty good; it would require some pixel peeping to see the difference between the f/1.4 primes and these if they were all shot at f/8.

Lensrentals.com, 2019

The more expensive f/1.4 primes, then, are better than the less expensive primes at wide apertures. They’re ‘laboratory’ better even stopped down, but at f/8 the difference is fairly small. If I was shooting stopped down, I’d personally prefer the lighter weight and lower costs. If I was shooting at, say, f/2.8 and wider much of the time, I’d have to seriously consider the better image quality of the f/1.4 lenses.

Now for Some Zooms

Let’s explore the other thing I hear a fair amount; “I don’t need primes because I shoot everything stopped down.” We’ll look at two 24-70mm f/2.8 zooms at 35mm for this comparison, the Sigma 24-70mm f/2.8 DG OS Art and the Canon 24-70mm f/2.8L USM Mk II. The Sigma is a good zoom at a price lower than the Canon or Zeiss 35mm f1.4 primes. The Canon is a really good zoom at a higher price.

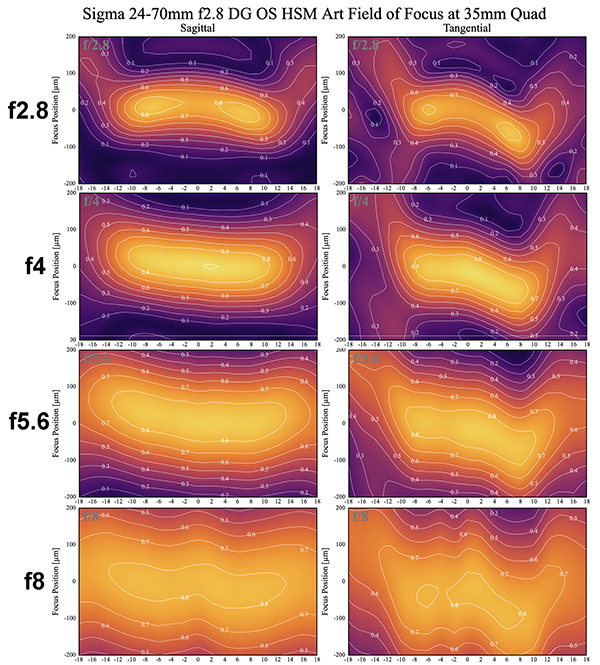

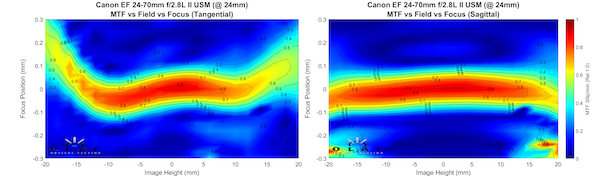

Sigma 24-70mm f2.8

A couple of things to note. First, compared to the primes, the field curvature on the tangential field is more dramatic than what we saw for primes. The edges aren’t as sharp wide open. There’s also more field tilt than the primes had. All of this is pretty much typical zoom; we’ll talk about the fields more in the last section of the article.

Lensrentals.com, 2019

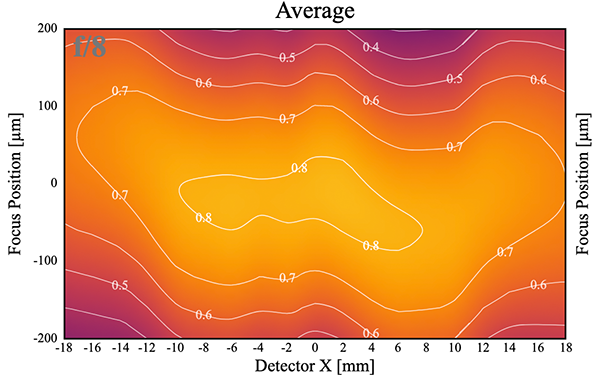

You really need to be at least f5.6 to get reasonable edge sharpness with this lens, but by f/8 it’s resolving fairly well. The tilt is enough that you’d notice it if you checked carefully, but again, that’s zooms for you. And yes, I know many of you can’t wait to tell me that you have perfect zooms. You don’t but I won’t ruin your fantasy for you just yet. I’ll just say, as we do in the South, “how nice!”

Lensrentals.com, 2019

The bottom line is this zoom, stopped down to f/8 is probably good enough for most people to use for a landscape image. It’s going to have more astigmatism and field curvature out at the edges than the f/1.8 primes did, but it would still be just fine for most people most of the time. I don’t think most people would want to do architectural photos with it, though. The combination of slight edge softness, field curvature, and tilt would be a bit more than most (not all) of you would like.

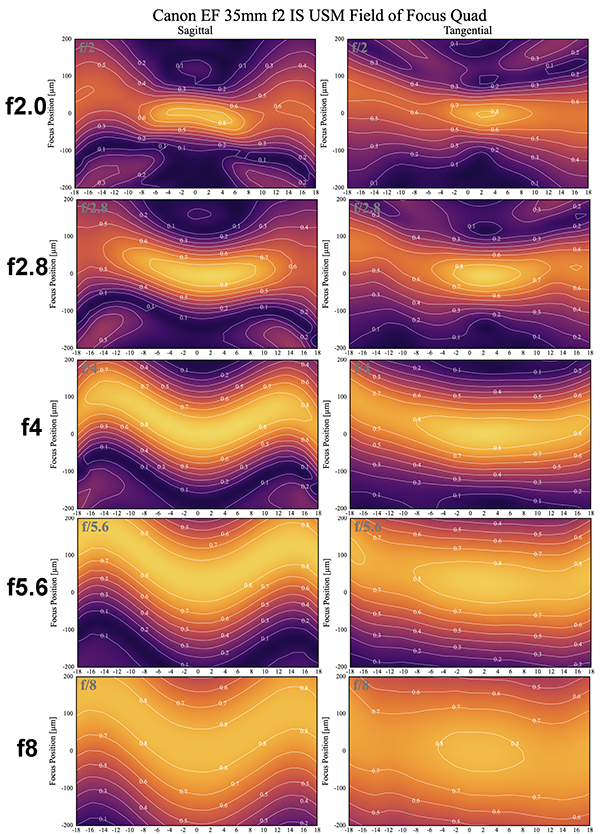

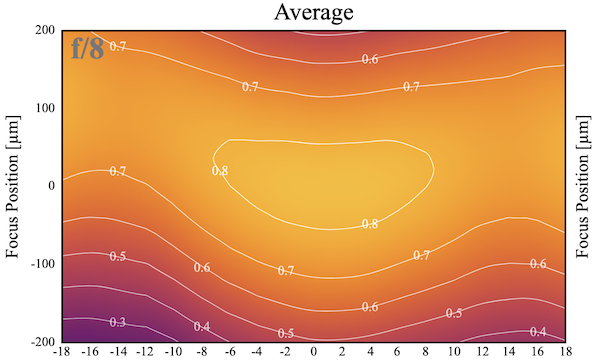

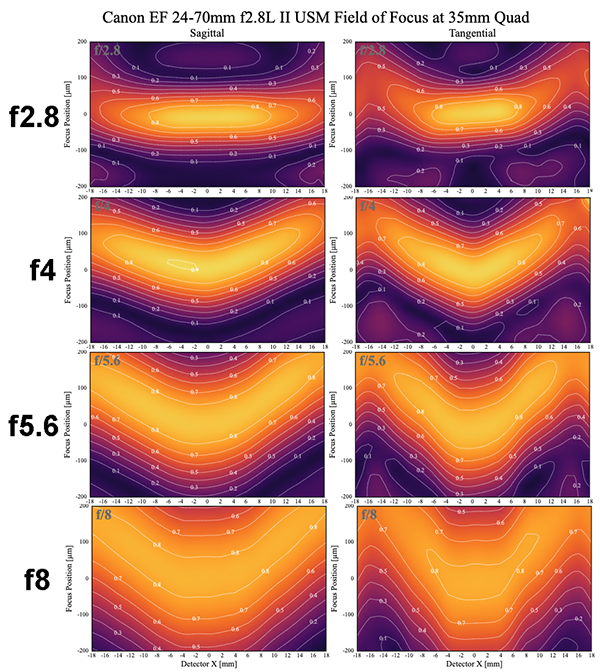

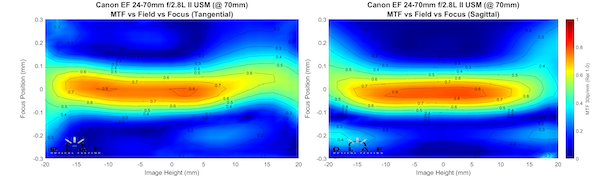

Canon 24-70 f2.8L Mk II

This gets a little interesting and also demonstrates a bit about why when someone asks if zoom X is better than zoom Y, my usual response is at what focal length and for what purposes? The Canon has better edge sharpness than the Sigma did. And the fields tend to overlap well; there’s not a ton of astigmatism.

Lensrentals.com. 2019

However, if you look at the field curvature, that edge sharpness is not in the same zip code as the best center sharpness. You can stop down to f/16 and you’re still not going to compensate for that curvature. (Before you Canon 24-70 owners start screaming about your copy not having field curvature like this, read the last sentence. Or I shall mock you.)

Does it matter? It depends on how you use the lens, what you use it for, and at what focal length. If it’s a landscape with a field of flowers, you might not care if the maximum flower sharpness is in an arc, not a line. If you’re doing architectural photography or a skyline, you would. For other purposes, you might prefer the better subject isolation the field curvature gives. If you take a group portrait, putting the group in an arc would keep everyone in focus, but a straight line of people would result in blurry ones at the edge.

My point is this tool would be quite different to use than the other 35mm lenses we’ve looked at. Great photographers know their tool well and use it to best effect. Many of them would be perfectly happy with this lens for most 35mm work.

One Other Thing About Zooms. Well, Several Things, Really.

A Roger’s Rule for you: All Zooms have multiple personalities.

You’re probably aware that zooms are sharper at some focal lengths than they are at others. This is both on average and for specific copies. For example, the Canon 24-70mm f/2.8 we just looked at is, on average sharpest at 24mm, less sharp at 50mm, and really a bit soft at 70mm. There are a few copies, though that are sharpest at around 50mm. I’ve seen one or two that were sharpest at 70mm.

You may not be aware that the field curvature also changes at different focal lengths. The Canon has a wicked field curve at 35mm we showed you above. At 70mm, though, it’s almost perfectly flat (although less sharp).

Lensrentals.com, 2017

At 24mm the fields no longer match, with a “W” curve in the tangential field, and a sagittal curve that’s slight, but in the opposite direction. So it has significant astigmatism at 24mm, less at 35mm very little at 70mm.

Does this really matter? Only if you want to make best use of your tool. You can frame a shot to make field curvature complement it. But you have to know what the field curvature looks like at different focal lengths to do that. I will add, this is one of the reasons I chose 24-70mm lenses for this comparison, they almost all have significant changes in field curvature from one end to the other. In general, 70-200mm have less dramatic change, zooms greater than 4X more dramatic change, and wide-angle zooms are a bit more random.

Lensrentals.com, 2017

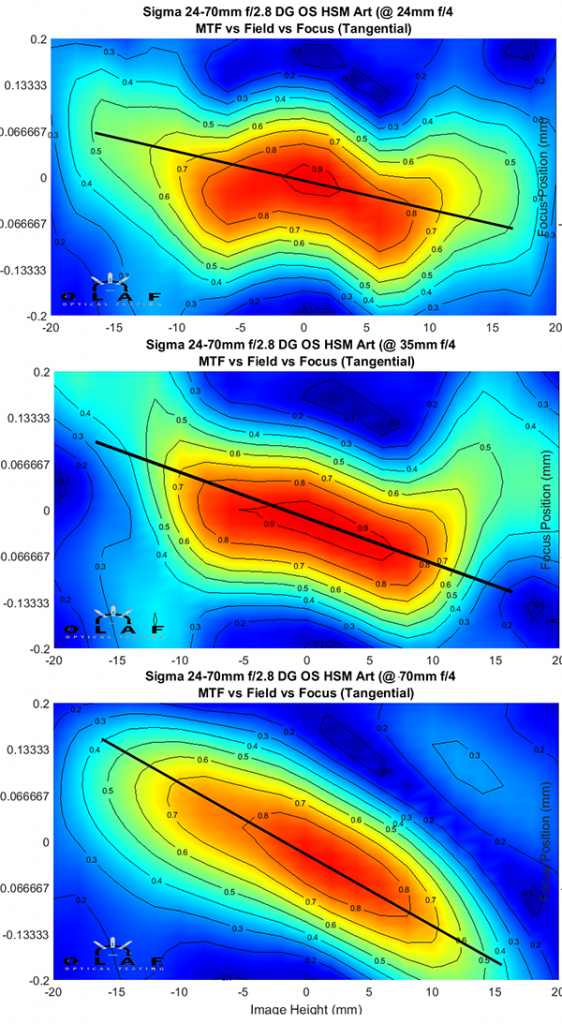

The other thing that happens with zooms, almost always, is the tilt varies at different focal lengths in each copy. In the Canon lens above there’s a bit of field tilt at 24m that goes away at 35mm, to be replaced by a bit of decentering at 70mm.

You may remember the Sigma 24-70mm we did above had more significant tilt. Here it is at 3 focal lengths, and I’ve added the line of tilt in an overlay. You can see the tilt increases as you move from 24mm to 70mm.

Lensrentals.com, 2019

The main takeaway from this is that zooms are less interchangeable than primes, copy variation is much more noticeable. If you make a general statement about zooms (like I did above for the Canon 24-70s sharpness) be very aware there will be a lot of copies that behave differently.

This is how zooms are. If you ask me to find a zoom that has no field tilt or centering change throughout the range, I’d tell you it’s not worth me testing a hundred copies in the faint hope of finding one.

Conclusions:

I think it’s pretty obvious, at least for lenses shot at 35mm. If you plan on shooting stopped down, a good f/1.8 or f/2 prime is nearly, but not absolutely, as good as the more expensive f/1.4 primes. A good zoom lens, even stopped down, is not as good as the inexpensive prime, at least at the edges of the image, but it will be close enough for most people most of the time. Depending on their copy. The zoom is going to be less predictable and have more variation, so that answer is a bit more copy specific.

That doesn’t mean you can’t take nice landscapes and other images with a zoom; lots of people do. It does mean it’s worth taking a little time to learn the field curvature and stop-down behavior of your zoom at various focal lengths if you want to use it to best effect.

Zooms have other advantages, of course. You don’t have to carry as many lenses or change them as frequently, you can often frame the image better.

A zoom is often the best choice of lens. But it’s never the best lens.

Roger Cicala and Aaron Closz

Lensrentals.com

November, 2019

Addendum: So How Do You Check Your Field Curvature.

Yes, I agree it will be nice if I put out field curvatures for every lens. I may do that for some of the more popular lenses, but I’m not going to do them all, and I’m not going to do all the focal lengths of every zoom. But it is something you could, if you want, check for at home. You can even check more than I can, since I’m just testing at infinity.

My personal favorite way to do this is to find a fairly large area with lots of regular small shapes in it. A field of grass, gravel, mulch, etc. works well. I put something in the center I can focus on and take an image at a shallow angle. For example, if I’m shooting a fair distance (10 or more meters) away I can stand up and take the image of a field of grass. If I’m shooting at close distances (a meter or two) I want the camera close to ground level.

I take the images and run them through something like Photoshop’s Find Edges filter, which will identify the areas that are in best focus and gives me a pretty nice printout of the field curvature.

Roger Cicala, 2016

This article has some more examples of this technique in the last section. As a bonus, if your lens is badly tilted, that will show up when you do this.

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Tord55

-

Tord55

-

Sator Photo

-

Thinkinginpictures

-

SpecialMan

-

Astro Landscapes

-

Astro Landscapes

-

Chris Newman

-

Athanasius Kirchner

-

Bob Locher

-

Roger Cicala

-

Roger Cicala

-

Lee Wooten

-

Brandon Dube

-

numbertwo

-

Roger Cicala

-

Athanasius Kirchner

-

Bob Locher

-

Roger Cicala

-

Ra Ho

-

David Bateman

-

Roger Cicala

-

Roger Cicala

-

Kers

-

El Aura

-

David Bateman

-

Marcello Mura

-

Federico Ferreres

-

Dave Hachey

-

Jeremy Wright