Technical Discussions

Sensor Size Matters – Part 2

Why Sensor Size Matters

Part 1 of this series discussed what the different sensor sizes actually are and encouraged you to think in terms of the surface area of the sensors. It assured you the size of the sensor was important, but really didn’t explain how it was important (other than the crop-factor effect). This article will go into more detail about how sensor size, and its derivative, pixel size, affect our images. For the purists among you, yes, I know “sensel” is the proper term rather than “pixel.” This stuff is confusing enough without using a term 98% of photographers don’t use, so cut me some slack.

I’ve made this an overview for people who aren’t really into the physics and mathematics of quantum electrodynamics. It will cover simply “what happens” and some very basic “why it happens.” I’ve avoided complex mathematics, and don’t mention every possible exception to the general rule (there are plenty). I’ve added an appendix at the end of the article that will go into more detail about “why it happens” for each topic and some references for those who want more depth.

I’ll warn you now that this post is too long – it should have been split into two articles. But I just couldn’t find a logical place to split it. My first literary agent gave me great advice for writing about complex subjects: “Tell them what you’re gonna tell them. Then tell them. And finally, tell them what you told them.” So for those of you who don’t want to tackle 4500 words, here’s what I’m going to tell you about sensor and pixel size:

- Noise and high ISO performance: Smaller pixels are worse. Sensor size doesn’t matter.

- Dynamic Range: Very small pixels (point and shoot size) suffer at higher ISO, sensor size doesn’t matter.

- Depth of field: Is larger for smaller size sensors for an image framed the same way as on a larger sensor. Pixel size doesn’t matter.

- Diffraction effects: Occur at wider apertures for both smaller sensors and for smaller pixels.

- Smaller sensors do offer some advantages, though, and for many types of photography their downside isn’t very important.

If you have other things to do, are in a rush, and trust me to be reasonably accurate, then there’s no need to read further. But if you want to see why those 5 statements are true (most of the time) read on! (Plus, in old-time-gamer-programming style, I’ve left an Easter Egg at the end for those who get all the way to the 42nd level.)

Calculating Pixel Size

Unlike crop factor, which we covered in the first article, some of the effects seen with different sensor sizes are the result of smaller or larger pixels rather than absolute sensor size. Obviously if a smaller sensor has the same number of pixels as a large sensor, the pixel pitch (the distance between the center of two adjacent pixels) must be smaller. But the pixel pitch is less obvious when a smaller sensor has fewer pixels. Quick, which has bigger pixels: a 21 Mpix full-frame or a 12 Mpix 4/3 camera?

Pixel pitch is easy to calculate. We know the size of the camera’s sensor and the size of its image in pixels. Simply dividing the length of the sensor by the number of pixels along that length gives us the pixel pitch. For example, the full-frame Canon 5D Mk II has an image that is 5616 x 3744 pixels in size, and a sensor that is 36mm x 24mm. 36mm / 5616 pixels (or 23mm / 3744 pixels) = 0.0064mm/pixel (or 6.4 microns/pixel). We can usually use either length or width for our calculation since since the vast majority of sensors have square pixels.

To give some examples, I’ve calculated the pixel pitch for a number of popular cameras and put them in the table below.

Table 1: Pixel sizes for various cameras

| Pixel size | Camera |

| (microns) | |

| 8.4 | Nikon D700, D3s |

| 7.3 | Nikon D4 |

| 6.9 | Canon 1D-X |

| 6.4 | Canon 5D Mk II |

| 5.9 | Sony A900, Nikon D3x |

| 5.7 | Canon 1D Mk IV |

| 5.5 | Nikon D300s, Fuji X100 |

| 4.8 | Nikon D7000, D800, Sony NEX 5n, Fuji X Pro 1 |

| 4.4 | Panasonic AG AF100, |

| 4.3 | Canon GX1, 7D; Olympus E-P3 |

| 3.8 | Panasonic GH-2, Sony NEX-7 |

| 3.4 | Nikon J1 / V1 |

| 2.2 | Fuji X10 |

| 2.0 | Canon G12 |

A really small pixel size, like those found in cell phone cameras and tiny point and shoots, would be around 1.4 microns (1). To put that in perspective, if a full-frame camera had 1.4 micron pixels it would give an image of 25,700 x 17,142 pixels, which would be a 440 Megapixel sensor. Makes the D800 look puny, now, doesn’t it? Unless you’ve got some really impressive computing power you probably don’t have much use for a 440 megapixel image, though. Anyway, you don’t have any lenses that would resolve it.

Effects on Noise and ISO Performance

We all know what high ISO noise looks like in our photographs. Pixel size (not sensor size) has a huge effect (although not the only effect) on noise. The reason is pretty simple. Let’s assume every photon that strikes the sensor is converted to an electron for the camera to record. For a given image (same light, aperture, etc.) X number of photons hits each of our Canon G12’s pixels (these are 2 microns on each side, so the pixel is 4 square microns in surface area). If we expose our Canon 5D Mk II to the same image, each pixel (6.4 micron sides, so 41 square microns in surface area) will be struck by 10 times as many photons, sending 10 times the number of electrons to the image processor.

There are other electrons bouncing around in our camera that were not created by photons striking the image sensor (see appendix). These random electrons create background noise – the image processor doesn’t know if the electron came from the image on the sensor or from random noise.

Just for an example, let’s pretend in our original image one photon strikes every square micron of our sensor, and both cameras have a background noise equivalent to one electron per pixel. The smaller pixels of the G12 will receive 4 electrons from light rays reaching each pixel of the sensor (4 square microns) for each pixel of noise (4:1 signal-to-noise ratio) while the 5DII will receive 41 electrons from each pixel (41:1 signal-to-noise ratio). The electronic wizardry built into our camera may be able to make 4:1 and 41:1 look pretty similar.

But let’s then cut the amount of light in half, so only half as many photons strike each sensor. Now the SNR ratios are 2:1 and 20:1. Maybe both images will look OK. Of course we can amplify the signal (increase ISO) but that also increases the amount of noise in the camera. And if we cut the light in half again and the SNR is now 1:1 and 10:1. The 5DII still has a better SNR ratio at this lower light than the G12 had in the original image. But the G12 has no image at all: the signal (image) strength is no greater than the noise.

That’s an exaggerated example, the difference isn’t actually that dramatic. The sensor absorbs far more than 40 photons per pixel and there are several other factors that influence how well a given camera handles high ISO and noise. If you want more detail and facts, there’s plenty in the appendix and the references. But the takeaway message is smaller pixels have lower signal to noise ratios than larger pixels.

Newer cameras are better than older cameras, but . . . .

It is very obvious that newer cameras handle high ISO noise better than cameras from 3 years ago. And just as obvious is that some manufacturers do a better job handling high ISO than others (Some of them cheat a lot to do it, with in-camera noise reduction even in RAW images that can cause loss of detail – but that’s another article someday).

People often get carried away with this, thinking newer cameras have overcome the laws of physics and can shoot at any ISO you would please. They are better, there’s no question about it, but the improvements are incremental and steady. DxO optics has tested a lot of sensors for a pretty long time and has graphed the improvement they’ve seen in signal to noise ratio, normalized for pixel size. The improvement over the last few years is obvious, but on the order of 20% or so, not a doubling or tripling for pixels of the same size.

Signal to noise ratio, normalized for pixel size. (DxO optics)

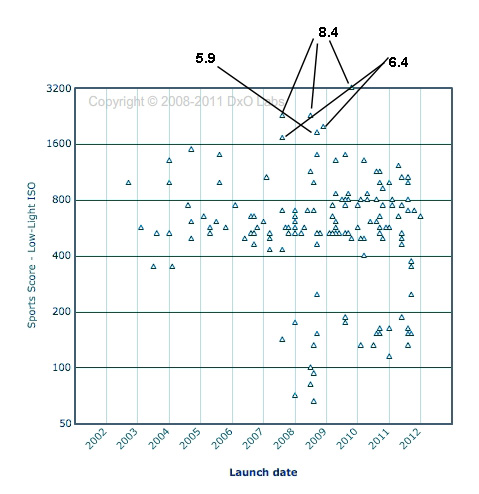

Other things being equal (same manufacturer, similar time since release), a camera with bigger pixels has less noise than one with smaller pixels. DxO graphs ISO performance for all the cameras they test. If you look at the cameras with the best ISO performance (top of the graph) they aren’t the newest cameras, they’re the ones with the largest pixels. In fact, most of them were released several years ago.

DxO Mark score for high ISO performance, with pixel size of the best cameras added.

The “miracle” increase in high ISO performance isn’t just about increased technology. It’s largely about decisions by designers at Canon, Nikon, and Sony in 2008 and 2009 to make cameras with large sensors containing large pixels. There is a simple mathematical formula for comparing the signal-to-noise ratio for different pixel sizes: the signal to noise ratio is proportional to the square root of the pixel pitch. There is more detail about it in the appendix.

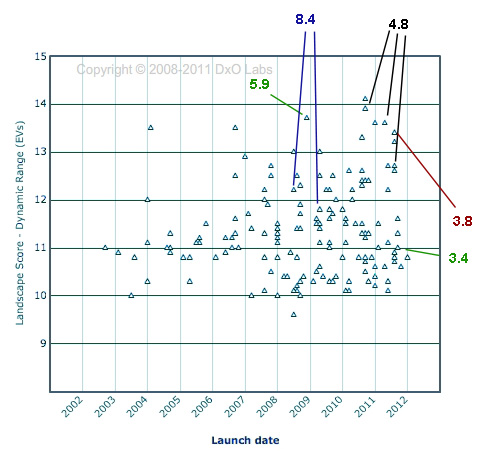

Effects on Dynamic Range

You might think the effects of pixel size on dynamic range should be similar to that of noise, discussed above. However, dynamic range seems to be the area where manufacturers are making the greatest strides – at least with reasonably sized pixels. When measured at ideal ISO (ISO 200 for most cameras) dynamic range varies more by how recently the camera was produced than by how large the pixels are (at least until the pixels get quite small). If you look at DxO Mark’s data for sensor dynamic range the cameras with the best dynamic range are basically newer cameras, not those with the largest pixels.

DxO Dynamic range scores with pixel sizes added for certain cameras. Recent release date seems much more important than pixel size.

There is no simple formula for calculating the effect of pixel size on dynamic range, but in general both large and medium size pixel sensors do well at low ISOs, but dynamic range falls more dramatically at higher ISOs for smaller pixels.

Effects on Depth of Field

Depth of field is a complex subject and takes some complex math to calculate. But the principles behind it are simple. To put it in words, rather than math, every lens is sharpest at the exact distance where it is focused. It gets a bit less sharp nearer and further from that plane. For some distance nearer and further from the plane of focus, however, our equipment and eyes can’t detect the difference in sharpness and for all practical purposes everything within that range appears to be at sharpest focus.

The depth of field is affected by 4 factors: the circle of confusion, lens focal length, lens aperture, and distance of the subject from the camera. Pixel size has no effect on depth of field, but sensor size has a direct effect on the circle of confusion, and the crop factor may also affect our choice of focal length and shooting distance. Depending on how you look at things, the sensor size can make the depth of field larger, shallower, or not change it at all. Let’s try to clarify things a bit.

Circle of Confusion

The circle of confusion causes a lot of confusion. But basically it is a measure of how large of a circle appears, to our vision, to be just a point (rather than a circle). It is determined (with a lot of argument about the specifics) from its size on a print. Obviously to make a print of a given size, you have to magnify a small sensor more than a large sensor. That means a smaller circle on the smaller sensor would be the limits of our vision, hence the circle of confusion is smaller for smaller sensor sizes.

There is more depth to the discussion in the appendix (and it’s actually rather interesting). But if you don’t want to read all that, below is a table of the circle of confusion (CoC = d/1500) size for various sensors.

Table 2: Circle of Confusion for Various Sensor Sizes

| Sensor Size | CoC |

| Full Frame | 0.029 mm |

| APS-C | 0.018 mm |

| 1.5″ | 0.016 mm |

| 4/3 | 0.015 mm |

| Nikon CX | 0.011 mm |

| 1/1.7″ | 0.006 mm |

The bottom line is that the smaller the sensor size, the smaller the circle of confusion. The smaller the circle of confusion, the shallower the depth of field – IF we’re shooting the same focal length at the same distance. For example, let’s assume I take a picture with a 100mm lens at f/4 of an object 100 feet away. On a 4/3 sensor camera the depth of field would be 37.7 feet. On a full frame camera it would be 80.4 feet. The smaller sensor would have the shallower depth of field. Of course, the images would be entirely different – the one shot on the 4/3 camera would only have an angle of view half as large as the full frame.

That’s all well and good for the pure technical aspect, but usually we want to compare a picture of a given composition between cameras. In that case we have to consider changes in focal length or shooting distance and the effects those have on depth of field.

Lens Focal Length and Shooting Distance

In order to frame a shot the same way (have the same angle of view), with a smaller sensor camera we must either use a wider focal length, step back further from the subject, or a bit of both. If we use either a wider focal length, or shoot at a greater distance from the subject, keeping the same angle of view, then the depth of field will be increased. This increase more than offsets the decreased depth of field you get from the smaller circle of confusion.

In the above example, I take a picture with a full-frame camera using a 100mm lens at a subject 100 feet distant at f/4. The depth of field was 80.4 feet. If I want to frame the picture the same way on a 4/3 camera I could use a 50mm lens (same distance and aperture). The depth of field would then be 313 feet. If instead I kept the 100mm lens but backed up to 200 feet distance to keep the same angle of view, the depth of field would be 168 feet. Either way, the depth of field for an image framed the same way will be much greater for the smaller sensor size than for the larger one.

So if we compare a similar image made with a small sensor or a large sensor, the smaller sensor will have the larger depth of field.

Compensating with a Larger Aperture

Since increasing the aperture narrows the depth of field, can’t we just open the aperture up to get the same depth of field with a smaller sensor as with a larger one? Well, to some degree, yes. In the example above the best depth of field I could get with a 4/3 sensor was 168 feet by keeping the 100mm lens and moving back to 200 feet. If I additionally opened the aperture to f/2.8 and then f/2.0 it would decrease the depth of field to 141 feet and 84 feet respectively. So in this case I’d need to open the aperture two stops to get a similar depth of field as I would using a full frame camera.

The relationships between shooting distance, focal length and aperture are complex and no one I know can keep it all in their head. If you move back and forth between formats a depth of field calculator is a must. And just to be clear: the effects on depth of field have nothing to do with pixel size, it’s simply about sensor size, whether the pixels on the sensor are large or small.

Effects on Diffraction

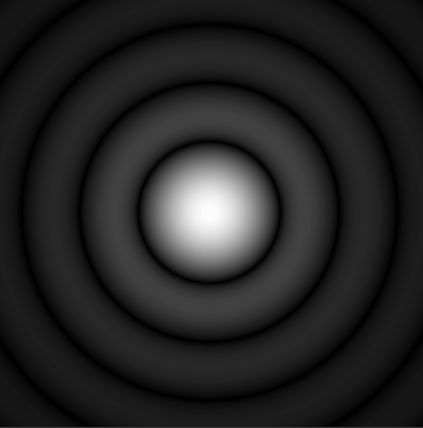

Everyone knows that when we stop a lens down too far the image begins to get soft from diffraction effects. Most of us understand roughly what diffraction is (light rays passing through an opening begin to spread out and interfere with each other). A few have gone past that and enjoy stimulating after-dinner discussions about Airy disc angular diameter calculations and determing Raleigh Criteria. A very few.

For the rest of us, here’s the simple version: When light passes through an opening (even a big opening), the rays bend a bit at the edges of the opening (diffraction). This diffraction causes what was originally a point of light (like a star, for example) to impact on our sensor as a small disc or circle of light with fainter concentric rings around it. This is known as the Airy disc (first described by George Airy in the mid 1800s).

A computer generated Airy Disc (courtesy Wikepedia Commons)

The formula for calculating the diameter of the Airy disc is (don’t be afraid, I have a simple point here, I’m not going all mathematical on you):

The point of the formula is to show you that the diameter of the airy disc is determined entirely by ? (the wavelength of light) and d (the diameter of the aperture). We can ignore the wavelength of light and just say in words that the Airy disc gets larger as the aperture gets smaller. At some point, obviously, the Airy disc gets large enough to cause diffraction softening.

At what point? Well, using the formula we can calculate the size of the Airy disc for every aperture (we have to choose one wavelength so we’ll use green light).

Table 3: Airy disc size for various apertures

| Airy disc | |

| Aperture | (Microns) |

| f/1.2 | 1.6 |

| f/1.4 | 1.9 |

| f/1.8 | 2.4 |

| f/2 | 2.7 |

| f/2.8 | 3.7 |

| f/4 | 5.3 |

| f/5.6 | 7.5 |

| f/8 | 10.7 |

| f/11 | 14.7 |

| f/13 | 17.3 |

| f/16 | 21.3 |

| f/22 | 29.3 |

Remember the circle of confusion we spoke of earlier? If the Airy disc is larger than the circle of confusion then we have reached the diffraction limit – the point at which making the aperture smaller is actually softening the image. In Table 2 I listed the size of the CoC for various sensor sizes. A smaller sensor means a smaller CoC so the diffraction limit occurs at a smaller aperture. Comparing the CoC (Table 2) with Airy disc size (Table 3) it’s apparent that a 4/3 sensor is becoming diffraction limited by f/11, a nikon J1 by f/8, and a 1/1.7″ crop sensor camera between f/4 and f/5.6.

But the size of the sensor gives us the highest possible f-number we can use before diffraction softening sets in. If the pixels are small they may cause diffraction softening at an even larger aperture (smaller f-number). If the Airy disc diameter is greater than 2 (or 2.5 or 3 – it’s arguable) pixel widths then diffraction softening can occur. If we calculate when the Airy disc is larger than 2.5 x the pixel pitch rather than when it is larger than the sensor’s circle of confusion things look a bit different.

Table 4: Diffraction limit for various pixel pitches

| Pixel Pitch | 2.5 * PP | Example camera | Diffraction at |

| 8.4 | 21 | Nikon D700, D3s | f/16 |

| 7.3 | 18.3 | Nikon D4 | f/13 |

| 6.9 | 17.3 | Canon 1D-X | f/13 |

| 6.4 | 16.0 | Canon 5D Mk II | f/12 |

| 5.9 | 14.8 | Sony A900, Nikon D3x | f/11 |

| 5.7 | 14.3 | Canon 1D Mk IV | f/11 |

| 5.5 | 13.8 | Nikon D300s, Fuji X100 | f/10 |

| 4.8 | 12.0 | Nikon D7000, D800, Sony NEX 5n, Fuji X Pro 1 | f/9 |

| 4.4 | 11.0 | Panasonic AG AF100, | f/8 |

| 4.3 | 10.8 | Canon GX1, 7D; Olympus E-P3 | f/8 |

| 3.8 | 9.5 | Panasonic GH-2, Sony NEX-7 | f/8 |

| 3.4 | 8.5 | Nikon J1 / V1 | f/6.3 |

| 2.2 | 5.5 | Fuji X10 | f/4.5 |

| 2 | 5.0 | Canon G12 | f/3.5 |

Let me emphasize that neither of the tables above are absolute values. There are a lot of variables that go into determining where diffraction softening starts. But whatever variables you choose, the relationship between diffraction values and sensor or pixel size remains: smaller sensors and smaller pixels suffer diffraction softening at lower apertures than do larger sensors with larger pixels.

Advantages of Smaller Sensors (yes, there are some)

There are several advantages that smaller sensors and even smaller pixels bring to the table. All of us realize the crop factor can be useful in telephoto work (and please don’t start a 30 post discussion on crop factor vs magnification vs cropping). The practical reality is many people can use a smaller or less expensive lens for sports or wildlife photography on a crop-sensor camera than they could on a full-frame.

One positive of smaller pixels is increased resolution. This seems self-evident, of course, since more resolution is generally a good thing. One thing that is often ignored, particularly when considering noise, is that noise from small pixels is often less objectionable and easier to remove than noise from larger pixels. It may not be quite as good as it sounds in some cases, however, especially if the lens in front of the small pixels can’t resolve sufficient detail to let those pixels be effective.

An increased depth-of-field can also be a positive. While we often wax poetic about narrow depth of field and dreamy bokeh for portraiture, a huge depth of field with nearly everything in focus is a definite advantage with landscape and architectural work. And there are simple practical considerations: smaller sensors can use smaller and less expensive lenses, or use only the ‘sweet spot’ – the best performing center of larger lenses.

Like everything in photography: a different tool gives us different advantages and disadvantages. Good photographers use those differences to their benefit.

Summary:

The summary of this overlong article is pretty simple:

- Very small pixels reduce dynamic range at higher ISO.

- Smaller sensor size give an increased depth of field for images framed the same way (same angle of view).

- Smaler sensor sizes have diffraction softening at wider apertures compared to larger sensors.

- Smaller pixels have increased noise at higher ISOs and can cause diffraction softening at wider apertures compared to larger sensors.

- Depending on what your style of photography these things may be disadvantages, advantages, or matter not at all.

Given the current state of technology, a lot of people way smarter than me have done calculations that indicate what pixel size is ideal – large enough to retain the best image quality but small enough to give high resolution. Surprisingly they usually come up with similar numbers: between 5.4 and 6.5 microns (Ferrel, Chen). When pixels are smaller than this the signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range starts to drop, and the final resolution (what you can actually see in a print) is not as high as the number of pixels should theoretically deliver.

Does that mean you shouldn’t buy a camera with pixel sizes smaller than 5.4 microns? No, not at all. There’s a lot more that goes into the choice of a camera than that. And this seems to be the pixel size where disadvantages start to occur. It’s not like a switch is suddenly thrown and everything goes south immediately. But it is a number to be aware of. With smaller pixels than this you will see some compromises in performance – at least in large prints and for certain types of photography. It’s probably no coincidence that so many manufacturers have chosen the 4.8 micron pixel pitch as the smallest pixel size in their better cameras.

APPENDIX AND AMPLIFICATIONS

Effects on Noise and ISO Performance

A camera’s electronic noise comes from 3 major sources. Read noise is generated by the camera’s electronic circuitry and is fairly random (for a given camera – some cameras have better shielding than others). Fixed pattern noise comes from the amplification within the sensor circuitry (so the more we amplify the signal, which is what we’re doing when we increase ISO, the more noise is generated). Dark currents or thermal noise are electrons that are generated from the sensor (not from the rest of the camera or the amplifiers) without any photons impacting it. Dark current is temperature dependent to some degree so is more likely with long exposures or high ambient temperatures.

The example I used in this section is very simplistic and the electron and photon numbers are far smaller than reality. The actual SNR (or Photon/Noise ratio) is P/(P + r2 + t2)1/2 where P = photons, r= read noise and t= thermal noise. The photon Full Well Capacity (how many photons completely saturate the pixel’s ability to convert them to electrons), read noise and dark noise can all be measured and the actual data for a sensor or pixel calculated at different ISOs. The Reference Articles by Clark listed below present this in an in-depth yet readable manner and also present some actual data samples for several cameras.

If you want to compare how much difference pixel size makes for camera noise, you can do so pretty simply: the signal to noise ratio is proportional to the square root of the pixel pitch. For example, it should be a pretty fair to compare the Nikon D700 (8.4 micron pixel pitch, SqRt = 2.9) with the D3X (5.9 micron PP, SqRt = 2.4) and say the D3X should have a signal to noise ratio that is 2.4/2.9 = 83% of the D700. The J1/V1 cameras with its 3.4 micron pixels (SqRt = 1.84) should have a signal-to-noise ratio that is 63% of the D700. If, in reality, the J1 performs better than that when actually measured, we can assume Nikon made some technical advances between the release of the D700 and the release of the J1.

Effects on Dynamic Range

At their best ISO (usually about ISO 200) most cameras, no matter how small the sensor size, have an excellent dynamic range of 12 stops or more. As ISO increases, larger pixel cameras retain much of their initial dynamic range, but smaller pixels loose dynamic range steadily. Some of the improvement in dynamic range in more recent cameras come from improved Analogue to Digital (A/D) converters using 14 bits rather than 12 bits, but there are certainly other improvements going on.

Effects on Depth of Field

The formulas for determining depth of field are complex and varied: different formulas are required for near distance (near the focal length of the lens) such as in macro work and for normal to far distances. Depth of field even varies by the wavelength of light in question. Even then, calculations are basically for light rays entering from near the optical axis. In certain circumstances off-axis (wide angle) rays may behave differently. And after the calculations are made, practical photography considerations like diffraction blurring must be taken into account.

For an excellent and thorough discussion I recommend the Paul van Walree’s (Toothwalker) article listed in the references. For the two people who want to know all the formulas involved, the wikepedia reference contains them all, as well as their derivation.

Circle of Confusion

Way back when, it was decided that if we looked at an 8 X 10 inch image viewed at 10 inches distance (this size and distance were chosen since 8 X 10 prints were common and 10 inches distance placed it at the normal human viewing angle of 60 degrees) a circle of 0.2mm or less appeared to be a point. Make the circle 0.25mm and most people perceive a circle; but 0.2mm, 0.15mm, 0.1mm, etc. all appear to be just a tiny point to our vision (until it gets so small that we can’t see it at all).

Even if a photograph is blurred slightly, as long as the blur is less than the circle of confusion, we can’t tell the difference just by looking at it. For example in the image below the middle circle is actually smaller and sharper than the two on either side of the middle, but your eyes and viewing screen resolution prevent you from noticing any difference. If the dots represent a photograph from near (left side) to far (right side) we would say the depth of field covers the 3 central dots: the blur is less than the circle of confusion and they look equally sharp. The dots on either side of the central 3 are blurred enough that we can notice it. They would be outside the depth of field.

To determine the Circle of Confusion on a camera’s sensor we have to magnify the sensor up to the size of an 8 X 10 image. A small sensor will have to be magnified more than a large sensor to reach that size, obviously.

There is a simple formula for determining the Circle of Confusion for any sensor size: CoC = d / 1500 where d = diameter of the sensor. (Some authorities use 1730 or another number in place of 1500 because they define the minimum point we can visualize differently, but the formula is otherwise unchanged.) But whatever is used, the smaller the diameter of the sensor, the smaller the circle of confusion.

Effects on Diffraction

Discussing diffraction means either gross simplification (like I did above) or pages of equations. Frighteningly (for me at least) Airy caclulations are the least of it. There also is either Fraunhofer diffraction or Fresnel diffraction depending on the aperture and distance from the aperture in question, and a whole host of other equations with Germanic and old English names. If you’re into it, you already know all this stuff. If not, I’d start with Richard Feynman’s book QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter before tackling the references below.

If you want just a little more information, though, written in exceptionally understandable English with nice illustrations, I recommend Sean McHugh’s article from Camridge in Colour listed in the references. He not only covers it in far more detail than I do, he includes great illustrations and handy calculators in his articles.

One expansion on the text in the article. You may wonder why an Airy disc larger than 1 pixel doesn’t cause diffraction softening, why we choose 2, 2.5 or 3 pixels instead. It’s because the Bayer array and AA filter mean one pixel on the sensor is not the same as one pixel in the print (damn, that’s the first time ever I’ve thought that ‘sensel’ would be a better word than ‘pixel’). The effects of Bayer filters and AA filters are complex and vary from camera to camera, so there is endless argument about which number of pixels is correct. It’s over my head – every one of the arguments makes sense to me so I’m just repeating them.

Oh, Yeah, the Easter Egg

If you’ve made it this far, here’s something you might find interesting.

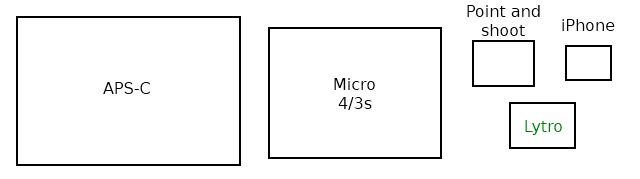

You’ve probably heard of the Lytro Light-Field Camera that supposedly lets you take a picture and then decide where to focus later. Lytro is being very careful not to release any meaningful specifications (probably because of skeptics like me who are already bashing the hype). But Devin Coldewey at TechCrunch.com has looked at the FCC photos of the insides of the camera and found the sensor is really quite small.

Sensor size of the Lytro Light Field Camera, courtesy TechCrunch.com

Lytros has published photos all over the place showing razor-sharp, narrow depth of field obtained with this tiny sensor. Buuuuutttt, given this tiny sensor, as Shakespeare would say, “I do smelleth the odor of strong fertilizer issuing forth from yon marketing department.” Focus on one part of the image after the shot? Even with an f/2.0 lens in front of it, at that sensor size the whole image should be in focus. Perhaps blur everywhere else after the shot? Why, wait a minute . . . you could just do that in software, now couldn’t you?

REFERENCES:

R. N. Clark: The Signal-to-Noise of Digital Camera Images and Comparison to Film

R. N. Clark: Digital Camera Sensor Performance Summary

R. N. Clark: Procedure for Evaluating Digital Camera Sensor Noise, Dynamic Range, and Full Well Capacities.

P. H. Davies: Circles of Confusion. Pixiq

R. Fischer and B. Tadic-Galeb: Optical System Design, 2000, McGraw-Hill

E. Hecht: Optics, 2002, Addison Wesley

S. McHugh: Lens Diffraction and Photography. Cambridge in Colour.

P. Padley: Diffraction from a Circular Aperture.

J. Farrell, F. Xiao, and S. Kavusi: Resolution and Light Sensitivity Tradeoff with Pixel Size.

P. van Walree: Depth of Field

Depth of Field – An Insider’s LookBehind The Scenes Zeiss Camera Lens News #1, 1997

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circle_of_confusion

Depth of Field Formulas: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Depth_of_field#DOF_formulas

R. Osuna and E. García: Do Sensors Outresolve Lenses?

T. Chen, et al.: How Small Should Pixel Size Be? SPIE

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

February, 2012

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Bob Newman

-

bobkoure

-

Raul Rodriguez

-

Jon

-

john wewege

-

Nqina Dlamini

-

seo companies in miami

-

Carl

-

Tom Cavanaugh

-

Carl

-

Carl

-

Carl

-

Tom Cavanaugh

-

Carl

-

Tom Cavanaugh

-

Carl

-

Tom Cavanaugh

-

Tom Cavanaugh

-

Carl

-

Tom Cavanaugh

-

David Rosenstein

-

Carl

-

Carl

-

Carl

-

Frank LLoyd

-

Knickerhawk