Lenses and Optics

There Is No Free Lunch, Episode 763: Lens Adapters

Lens adapters can be useful things sometimes, letting you mount one brand of lens on another brand of camera.

One thing that has always bothered me, though, is the idea of doubling the number of lens-mount interfaces. When you look at the thick metal pieces on the front of the camera and the back of the lens, and then consider that they have to be lined up exactly parallel to the image sensor, it’s kind of amazing it works.

Although it doesn’t always work. Lloyd Chambers first reported years ago that with high-quality, wide-angle lenses you could detect very small misalignments in the camera-lens mount. Misalignment of 10 microns from side-to-side was enough to cause blur on the sides of the image. Since then a lot of other people have confirmed the same thing.

So when I hear people cavalierly talking about putting an adapter on their camera I tend to cringe. When a single camera-lens interface has enough variability to sometimes be visible, adding another large piece of metal with another mount interface seems a recipe for problems.

Don’t get me wrong. Generally, they’re acceptable or people wouldn’t use them. But I always am curious about what acceptable looks like in the lab.

Optical Bench Testing

We’ve been working a lot with our optical bench, testing large enough quantities of each lens to develop our acceptable ranges, since we plan to start adding this testing to the Imatest testing we currently use for quality assurance. An optical bench isn’t necessarily better than image-based testing programs like Imatest, but it has some specific advantages.

One big difference is that an optical bench tests at infinity (on wide-angle lenses, Imatest or DxOAnalytics may be testing at 4-6 feet focusing distance). Another is it tests the lens directly; the variability of a camera body is eliminated from the loop. There are some things a bench doesn’t do as well, too. For example you don’t get a full picture of the entire lens in one run; you get a line of data from one side to the other. You have to rotate the lens in its mount and do several lines to get a complete picture of the entire lens surface.

Since the information from our optical bench is different from the Imatest graphs I usually use for illustrations, let me go over one quickly.

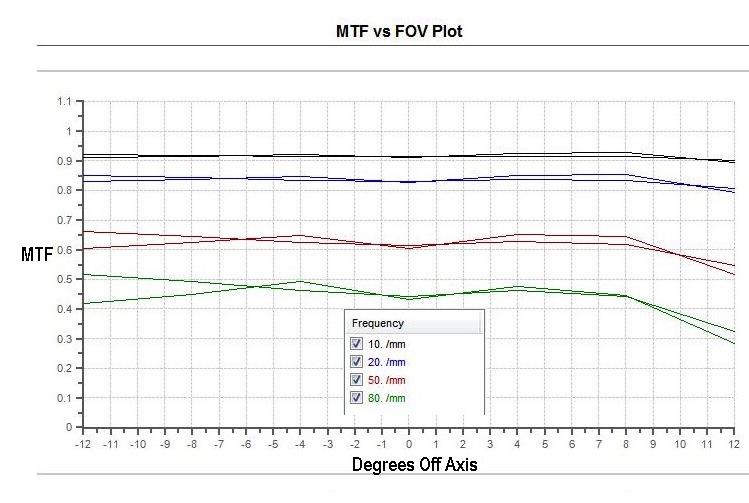

The horizontal axis shows degrees off-center, with “0” the center of the lens. The vertical axis is the MTF reading (“1” being theoretical perfection and “0” being gray mush).

The charted colors show various frequencies. For this graph we chose to show the MTF at 10, 20, 50, and 80 line pairs per mm. Most manufacturers’ MTF graphs limit themselves to 10 and 30 or 10, 20, and 40 as frequencies. We’re including some higher frequencies just because we’re still learning about using this tool to identify bad lenses.

There are two charted lines at each frequency, one representing tangential and the other sagittal lines. When the two lines of the same color are separated, there is some astigmatism. (You don’t have to worry about the terms – just that if the two lines of the same color are widely separated, that’s not good, close together is good.)

The graph above is of a good copy of a good lens, the Zeiss 35mm f/2.0. There are some slight differences away from center with one side having a bit more astigmatism and the other a bit lower MTF at higher frequencies, but this is really minor stuff that wouldn’t show up in photograph.

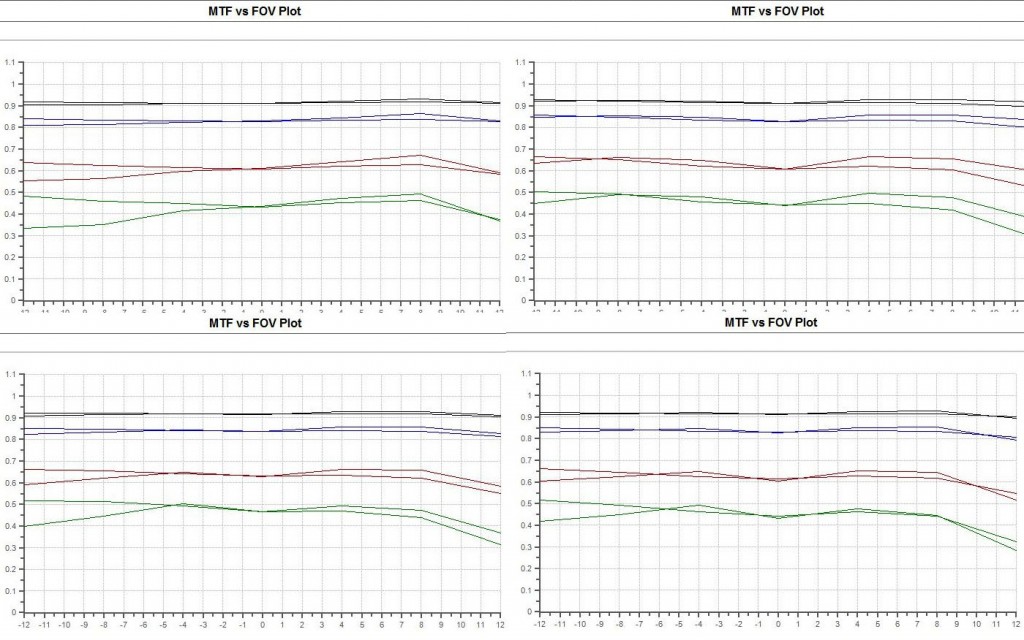

To give you a bit more experience with this kind of graph, below are printouts from 4 other Zeiss 35mm f/2.0 lenses – all of which are optically excellent as determined by Imatest and careful pixel-peeping.

Again, let me emphasize that what you’re seeing is normal (actually less than normal) copy-to-copy variation in good copies of the lens. Actual bench testing is almost like fingerprinting. No two copies are exactly the same. Notice the similarities. There is nearly no astigmatism right at the center and similar MTF values, particularly at the 10 and 20 /mm frequencies that are most critical.

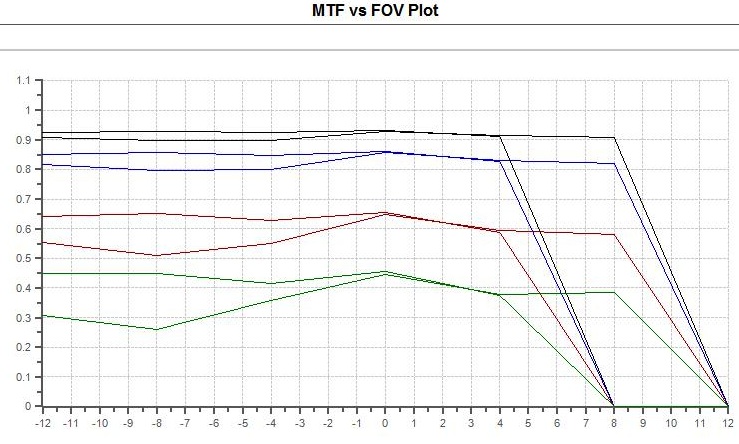

To give you some idea of what a not-so-good lens looks like on the same set of parameters, here’s one that’s not so good.

Notice this one is still quite good in the center, but has some major problems developing on the right side. The settings on the optical bench we used for this series make it look much worse than it really is. While the graph makes it look like the MTF drops to zero, that’s simply because the settings we’re using report zero if focusing distance changes greatly or vignetting become severe. That makes a nice warning signal for ‘some human needs to come check this lens’.

Our parameters are pretty tight: the awful looking graph above actually is a lens that looks a little softer on the right side, but certainly not horrible. An online sized jpg would look perfectly fine, at 50% pixel-peeping or in a large print you’d notice it. I’ll go into more detail about what we can do with the optical bench in some later posts; I just wanted to give you a quick overview for now.

Using Adapters on the Optical Bench

One thing you probably haven’t thought about is that lenses have to be mounted on the bench in order to do these tests. That requires a separate, fairly expensive mount for each brand of lens. Obviously we had to pony up to get mounts for Canon, Nikon, NEX, and Micro 4/3 lenses. But, since I was already pretty unpopular in the accounting department, I hoped to avoid spending a few thousand more dollars to buy Leica, PL, and other mounts for lenses that we have a lower number of copies of.

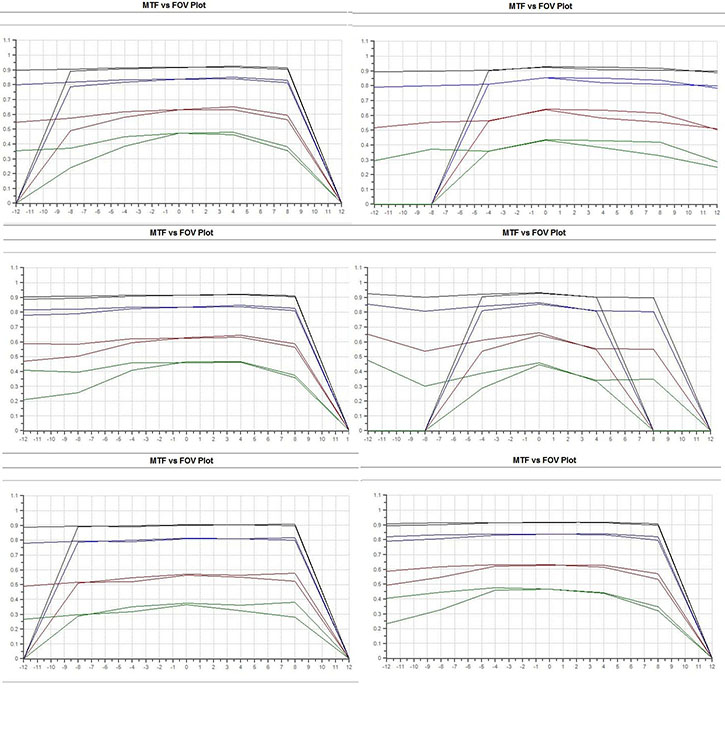

I knew adapters might cause a problem, but thought, since we carry so many copies of various high-quality adapters, I could certainly find a few that were accurate enough to use. Once again, Roger’s assumptions were way off base. I won’t bore you with dozens and dozens of test results. But I’ll show you a good example. In this case, we took the lens in the upper right of the 4 examples at the top of the page and tested it on a number of Nikon to NEX adapters. Here are 6 examples.

I won’t bore you with another 20 graphs that look pretty much like these. We tried Leica to NEX and Leica to Micro 4/3 adapters, Canon to NEX, etc. We tried different lenses on one adapter. It didn’t really matter. None of them would be acceptable for testing. Not one.

I won’t bore you with another 20 graphs that look pretty much like these. We tried Leica to NEX and Leica to Micro 4/3 adapters, Canon to NEX, etc. We tried different lenses on one adapter. It didn’t really matter. None of them would be acceptable for testing. Not one.

I’ll point out that we carry only name-brand, fairly expensive adapters, not eBay $29 adapters. All of them are tested frequently and used frequently and none of the ones I tested today had any problems. Still, not one of them would be acceptable for testing, so I guess I’m going to have to order those expensive lens mounts after all.

What Does It Mean in the Real World?

Like a lot of laboratory testing, probably not a lot. Adapters couldn’t all stink or people wouldn’t use them. Like a lot of tests, you can detect a very real difference in the lab that doesn’t make much difference at all in the real world.

Videographers are the primary users of adapters, and probably won’t notice the problems at all. Video and cinema cameras shoot at lower resolution (even 4K video) than photography and tend to concentrate on center-frame so they’re unlikely to see a problem.

Even photographers who use adapters are often adapting a larger format lens to a smaller format camera (Leica full-frame lens to Micro 4/3 or APS-C camera, for example). Assuming the lens is higher quality than a native lens they would otherwise be shooting, they might be perfectly happy. Still, I should point out that I only tested these 35mm lenses out to +/- 12 degrees (their field of view is actually +/- 30 degrees). Even on a Micro 4/3 camera, the lens would have a field of view of +/- 15 degrees what we see here at 12 degrees should be noticeable.

In the examples above, though, center resolution is pretty much unchanged, it’s only when you get away from center that you start to see issues. So someone shooting portraits and centered subjects is unlikely to notice an issue. A landscape photographer, though, would likely see some problems along the edges of the image.

Putting a great lens on your camera via an adapter might still be better than an average native-mount lens. On the other hand, that great lens certainly wouldn’t be as good as it would be on its native-mount camera.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

September, 2013

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Gianluca Gianferrari

-

KWNJr

-

Scott Kennelly

-

Mosawr Team

-

Terry

-

CarVac

-

Zos Xavius

-

Cane C.

-

John Hansen

-

Thomas

-

Douglas Anthony Cooper

-

Tord S Eriksson

-

Mike Sandman

-

tjshot

-

Tim Parkin

-

e17paul

-

Sem Svizec