Equipment

Canon 35mm f/1.4 Mk II Teardown

As soon as we optically tested the Canon 35mm f/1.4 Mk II lens we couldn’t wait to tear into one for a couple of reasons. One was that Canon has been making a lot of interesting advances in lens mechanics lately, so we’re always excited to look inside their new lenses. Another was that Canon claimed this lens had increased weather resistance and durability. You know I’m pretty cynical about claims like that until I see what’s inside for myself. And finally, well, it’s been really busy all fall and Aaron and I really just haven’t had time to tear apart some new lenses, so we were having withdrawal.

We got a little time this week, so we used it to take apart the new Canon 35mm f/1.4 Mk II. Those of you who like to follow along from home with your own lens go get your #2 JIS screwdriver and a spanner wrench and let’s get to work!

First the makeup decal on the front of the lens has to be peeled off.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

Next we use a spanner wrench to take off the front plastic ring.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

In most lenses rings like this hold the front element in place, but in this case, it seems the entire purpose of this ring is to improve weather resistance. (I refuse to use the term weather seal, and always will. No lens is weather sealed). It fits tightly around the glass and into the front barrel of the lens, and it has a rubber gasket for further sealing internally.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

With the weather resisting ring removed, we can looking into the barrel front and see two sets of 6 screws. The brass ones that are open to view hold on the filter barrel. The partially covered set appear to be holding the front group in place.

Lensrentals.com, 2015

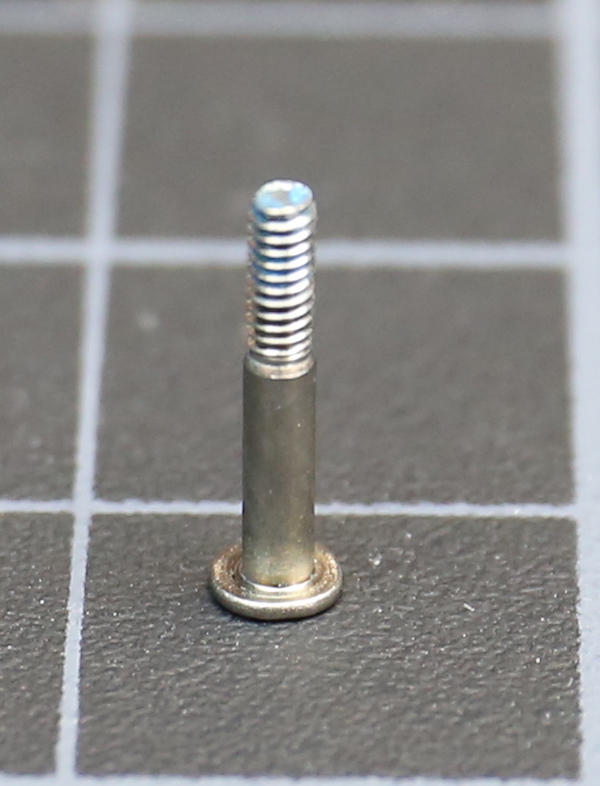

We were impressed with 6 screws to hold onto the filter barrel; most lenses use 3. We were even more impressed when we removed them. Each of the 6 screws is long, strong, and deeply threaded. Not the usual tiny screw assigned to a task like this.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

Lensrentals.com, 2015

And when the screw was removed, we found that each hole contained a brass reinforcing spacer with a spring around it. So basically each of the 6 screws passes through the brass spacer and screws into the front barrel, with a spring maintaining tension. This is an expensive way to do things and obviously serves a purpose. It may be to maintain even tension on the focusing ring (which is right below the filter barrel), to provide a more even stress distribution, or probably is for something else entirely. But just because I don’t know what it’s for doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate the careful attention to detail taken here.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

With the screws taken out the filter ring barrel comes right off. This will be a quick, simple replacement when the inevitable broken filter ring occurs.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

With the filter barrel off, we can see that the front group is attached with 6 screws through 6 thick plastic tabs. It’s not visible in the picture, but there’s also a copious amount of loctite around the screws and silicone glue under the tabs.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

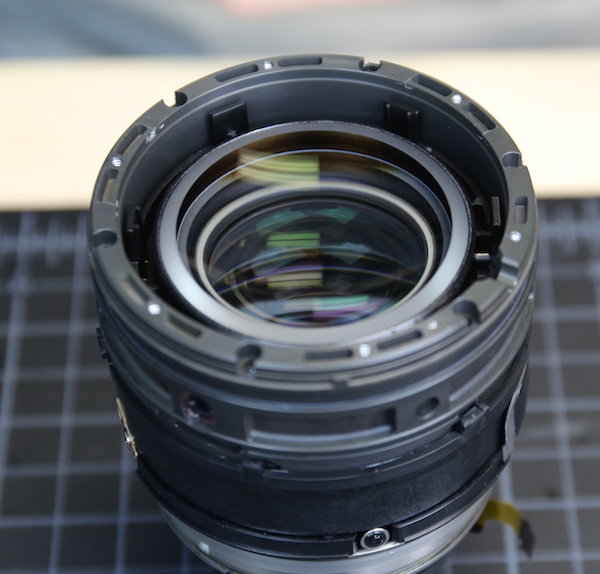

At this point, Aaron decided that the amount of glue on that element meant he might be doing some prying to get it out. Rather than do that blind, he decided to do some back-end disassembly first so we flipped the lens over and removed the bayonet mount.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

There is the usual thick Canon rear weather gasket around the bayonet.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

Underneath the bayonet is a black plastic spacing ring. The fact that it’s numbered suggests it comes in different thicknesses to adjust infinity focusing distance. Canon tends to use various-thickness bayonets or spacers like this rather than shims.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

A fairly standard Canon PCB with lots of flex connections is underneath the spacing ring.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

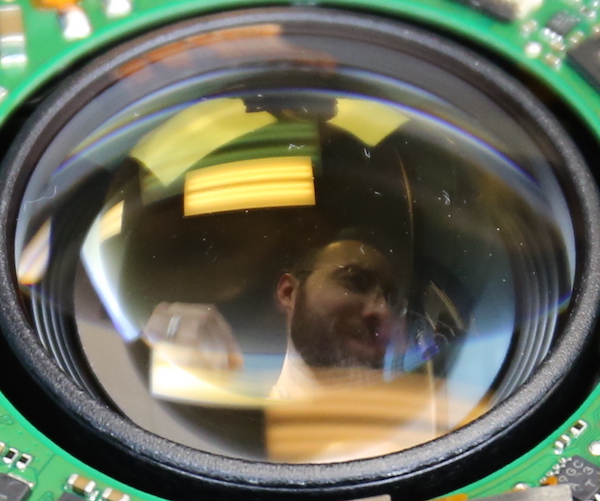

The rear glass does make a nice Selfie-Cam for Aaron.

With the PCB off, the screws holding the rear barrel in place are evident – again, multiple robust screws are used, not the minimal 3 screws we usually see.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

Removing those let us slide the rear barrel off and reveals the more interesting stuff; primarily at this point the rear group and focusing motor.

Lensrentals.com, 2015

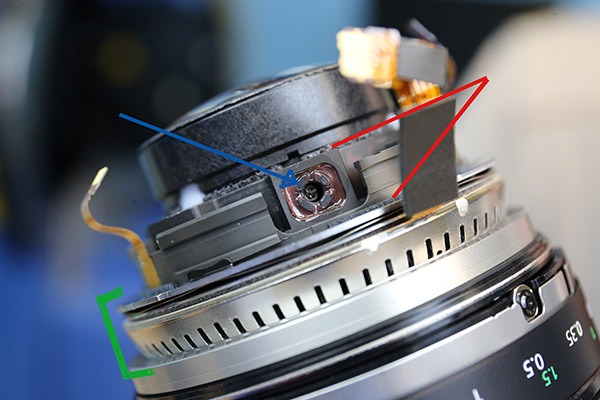

A closer look shows a couple of nice details. First there are two more layers of rubber felt sealing gaskets (red lines) between the rear of the lens and the AF Motor (green brackets). There’s also a very, very robust eccentric collar set (blue arrow) used to optically adjust the rear group. We consider thick nylon collars robust, brass collars very robust, but these massive heavy collars with a center locking screw are beyond anything we’ve seen outside of super telephoto lenses and the 70-200 f/2.8 IS II.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

You can also see that once adjusted into position, Canon has sealed the adjustment collars in plastic cement to prevent them from moving. For you that means they’re not likely to get moved during the life of the lens. For us that means we’ll have to pick the plastic cement out when we do adjustments. That’s OK, the pink cement isn’t too hard to get out.

Rather than take out those adjustment collars we went back to the front of the lens and removed the focusing rubber. Underneath that the ring is completely sealed in tough tape, covering all the holes (you’d be amazed how many supposedly ‘weather resistant’ lenses have huge gaping holes under the rubber).

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

With the tape off, the three plastic keys (white and round in the picture below) that hold the focus ring in place are exposed.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

These are large and require a special tool to remove properly, but once they’re out the focus ring slides off the front of the lens. Notice the part of the lens in Aaron’s left hand still contains all of the optical elements. Basically, all we’ve done so far is remove the mount and coverings.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

With the focus ring off, we can see another set of robust optical adjustment collars that adjust group 2. (Later experimentation hinted that these were primarily centering collars, with the rear collars primarily adjusting tilt.)

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

Turning the focus mechanism exposed the stays that the inner barrel rotates on. They aren’t the usual nylon bushings over screws, they are very large brass posts held in place by oversize screws. Again it’s something we’d expect to find in a large telephoto zoom, not a standard range prime.

Lensrentals.com, 2015

Since we discovered that group 2 and not group 1 was an adjustable group, we felt much more comfortable with prying up the glue and removing Group 1. At this point we weren’t at all surprised to find that not only was group 1 held in place by 6 screws (3 is the norm) but that they were some big, long screws at that.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

With the screws removed and a little heat applied to the glue, we were able to pry group one up and remove it. You can see that the top of the front group has a spanner ring holding the first element in place, so a scratched front element can be replaced separately without having to replace the entire front group. That’s a good thing. While I don’t know the cost of a front element yet, front groups like this are expensive, costing as much as $700. Being able to replace just the front element is a good thing, it will be less expensive and the front group doesn’t have to be removed to do it.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

Here’s a view inside the barrel with the front group removed. There are two points to make here. The first is minor, and hard to see from the photo, but the front of group 2 is really different and unusual. It’s a concave element with a large band of ground glass around the edge. It’s not important; just different, looks cool, and when one of these comes back dead from water damage I’m making a Christmas ornament out of it.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

The more important part the thick gray barrel of this lens. That’s heavy gauge metal. All the pieces of lenses we’ve removed attach to this heavy metal center barrel. This is unusual, but it’s so logical I want to weep with joy just for having seen it. I have rolled my eyes for years when people say a lens is “Built like a tank” because it has a heavy metal shell. Then we open it up and see the insides are tiny little screws and weak nylon collars set in thin sheet metal helicoids. That kind of ‘built like a tank’ is probably useful if you want your lens to stop a bullet, but doesn’t make the lens reliable.

This is my kind of built like a tank. There is a flexible polycarbonate shell over a very solid metal core with really heavy-duty rollers, screws, and bearings. That’s a logical way to build things; make the core the strongest part, not the shell. It sounds so simple, but like I said, this is the first time we’ve ever seen this kind of construction in a prime lens of standard focal length. We take apart A LOT of lenses (we passed 20,000 in-house repairs some time ago) and this is the most impressively built prime I’ve seen. This is an engineer’s lens.

At this point we had to decide whether we wanted to take apart the optical core of the lens. Doing so meant removing the large adjustment collars for the front group, and having to readjust the lens optically during reassembly. I spoke at length about why we should just stop here and put things back together. Aaron took out the collars and large brass posts we showed you earlier while I was talking, so I guess he didn’t hear me. After that the front half of the optics came right out of the central barrel (it’s being held in a rubber cone which is not part of the lens in the picture below).

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

And rotating it to line things up, the rear group could slide out from the focusing motor and barrel as well.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

With the USM motor and barrel off we can see the focusing helicoids and the heavy metal rollers that move the focusing elements within the helicoid. In almost every lens, these would be small nylon washers over a screw, not the relatively huge metal rollers we see in this lens.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

When you look close up you see these aren’t just sliding posts, there are actually tiny ball bearings inside them. There’s also a spring tensioning system around one of the rollers. I keep repeating myself, but by this point I was really rather awestruck by the amount of careful over-engineering that went into making this lens. Nobody, and I do mean nobody, else is engineering lens mechanics like the newer Canon lenses.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

Of course, we took one the rollers out to get a better look at it. This may look small to you, but the nylon collars used in other lenses are at most 1/4 of this size, aren’t metal, and don’t roll, they just slide.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

I’ll close with another view of the internal barrels in extended position, this time also showing the aperture control motor.

- Lensrentals.com, 2015

OK, this concludes the disassembly portion of our program. Those of you who have been disassembling your own lenses at home, just reverse the steps and it will go right back together, probably. Since someone always freaks out when we do a teardown and thinks we’ve made a sacrifice to the lens gods, I will mention that the lens was fully reassembled, Aaron optically adjusted it back to perfection, it’s been completely retested by our techs, and is working fine. Yes, it’s back in the rental fleet and no, it’s not going to have problems. This is what we do all day long.

Comments

I’m sure you can tell we’re impressed with the Canon 35mm f/1.4 Mk II. The weather resistance appears better than most weather resistant lenses. (As always, I’ll add that weather resistance still means water damage voids the warranty.) The mechanical construction is beyond impressive. This lens is massively over-engineered compared to any other prime we’ve ever disassembled. It’s built like a tank where it counts; on the inside. Moving parts are huge and robust. Six big screws are used in locations where 3 smalls screws are common in other lenses. Heavy roller bearings move the focusing group, it doesn’t slide on little nylon collars.

It’s also designed thoughtfully and logically. Things that will inevitably get damaged on any lens, like the front element and filter ring, are designed to be replaced easily. There are some things inside, particularly with the tensioning screws and springs, that I’m not certain I understand the purpose of, but I am certain there is a purpose. If I had to summarize the mechanical design of this lens, I would say simply that no expense was spared, no corner was cut.

Sometimes things are expensive because they’re worth it. Sometimes they’re heavy because they’re so solidly constructed. This is one of those times.

Roger Cicala and Aaron Closz

Lensrentals.com

December, 2015.

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

burgo

-

Andre

-

Jake Warrington

-

Hernan

-

Enzio Ardesch

-

Hernan

-

Enzio Ardesch

-

A-Sign

-

Dylan Howell

-

asiafish

-

kimH

-

Mark Laing

-

kimH

-

Neil Partridge

-

Brad A.

-

Lynn Allan

-

Riley Escobar

-

MPNavrozjee

-

Michael D. Rubin

-

Jack Zhan

-

LorinDuckman