Resolution Tests

Why Aren’t the Damn Numbers the Same????

I get asked a simple question almost every day: Why do your results say this, Joe’s results say that, and Bill’s results say something different? The questions surprised me at first; I grew up in biological and medical research and took it for granted everyone expected different tests to have slightly different results.

But different numbers makes things complicated. Everyone would like it if 5 reviewers all said the new Ultrazooma has an MTF50 of 816.5. That would be that. But obviously it’s not that simple. So why does Roger say 800, Joe says 1642, and Bill says 656? Plus, Roger says 800 is great, Joe says 1642 sucks, and Bill says 650 is average?

I’m going to talk about that, but fair warning: This is a geeky article. If you aren’t into this kind of thing you might want to save 15 minutes and go chat on a forum.

Image Analysis MTF Numbers

A lot of people evaluating lenses use Imatest, DxO Analyzer, or some similar computerized resolution tool. They all work roughly the same way: a controlled image of slanted lines or circles is taken and computer analyzed to determine the resolution of the camera and lens. The data can be presented in several ways. Imatest users commonly present MTF50 numbers but have several other options. DxO uses a ‘blur factor’ measurement that is proprietary.

Computerized Image Analysis is a big improvement on “It looks really sharp to me” versus “I didn’t think it was all that great.” But it also has several limitations:

- It tests a combination of lens and camera, not just lens.

- Testing is done at fairly short distances (10 – 50 feet) so it may differ significantly from values at infinite focusing distance.

- Each lab varies a bit. Lighting, testing distance, test charts used, etc. can make numbers slightly different between testers

- The same value may be reported in different numbers.

So why does everyone use image analsyis MTF? Because it’s accurate within its limitations and it’s reasonably priced. A good Imatest setup costs around $10,000 and gives reproducible numeric results that are more accurate than shooting a test chart. A good optical bench capable of measuring MTF across the entire lens costs 10 times as much.

An optical bench, though, has several advantages: it’s testing the lens at infinity, the variables of the camera are eliminated, and it provides greater accuracy. On the other hand, most can only measure the lens at infinity. Sometimes you want to know how a lens does at 20 feet rather than at 250 feet.

If you’re interested in the specifics of testing, I’ll go into some more specifics below. If not, those are the main points. Move on down to ‘The Single Copy Phenomenon” below.

The Range Chosen for Numbers

Even when presenting MTF 50 results, different testers will present their numbers differently. For example, I use line pairs / image height. Others might use lines / image height (so their number would be exactly double mine). They might also present lines (or line pairs) per mm instead of per image height. This is pretty simple, though. You can get out your calculator and compare line pairs per image height to lines per mm.

Were the Test Images RAW or JPG?

The Imatest results from an in-camera JPG will be significantly higher than if the test is run on a RAW image. How much higher varies depending upon the camera, but 20 to 40% higher is common.

Some testers use in-camera JPGs because they believe the results are more likely to approximate what people will actually see. Others use raw images to eliminate, as much as possible, any in-camera sharpening and reduce the chance of spurious resolution. Even different raw converters may give different results. Luckily most Imatest testers use the included DCraw converter so their results should be similar.

What Targets Were Measured from What Distance?

This is one area where most testers let you down — myself included. I know that few people want to read this stuff in an article, but I should have put it up somewhere before now. Other testers should too. But this is the kind of thing that has a lot to do with why Joe’s numbers and Bill’s numbers are still different after you convert them.

We’re taking pictures of special test targets. They come in various sizes, but they’re expensive (the largest charts are over $1,000 each). I use 6 sizes, ranging from 2″ X 3″ backlit photographic film (for macro testing) up to 42″ X 72″ factory-made prints. Since the chart must always completely fill the image, you can only shoot at certain distances. For example, even with our largest chart, a 16mm lens on a full frame camera is shot at about 8 feet distance.

Even with all the sizes, though, since the target must always fill the frame of the image, there are fixed distances you can shoot at. There can be significant differences on standard range distances. If I shoot a 70mm lens on our second largest chart, I’m shooting at about 14 feet. On the largest I’m back to 19 feet. On a smaller chart, I may be at 7 feet. The same lens, on the same camera, will give slightly different results shot at different distances.

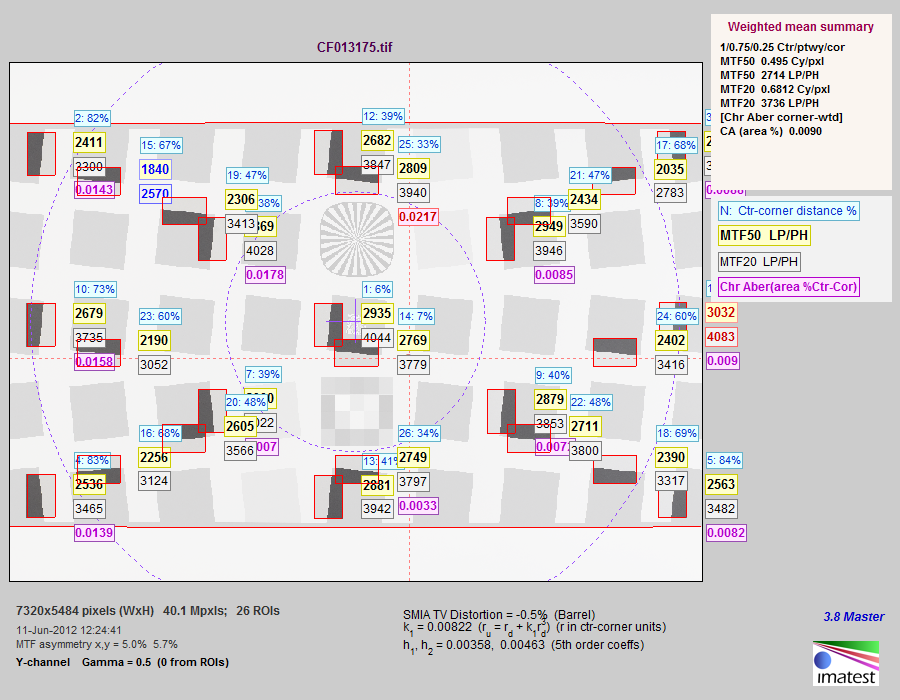

It also matters what part of the chart I take my measurements from. A typical Imatest image looks like the one below.

- An Imatest print out, showing which edges were measured (dark edges) and the measured numbers for each.

The edges of the light gray squares are what the computer actually measures. In this printout the computer has shown (by darker areas in red boxes) the parts of the chart used for calculations. This is the typical 13-point measurement I use when I give average results across the entire lens.

I could actually calculate over 30 points, but the calculations take a loooong time. But another reviewer might use 9 points or 24 or 32 to get his overall results. We should pretty well agree on the center value, but depending on the number of points used for calculations we might differ a bit on the average value.

One other thing can cause significant differences. In the example above I’ve measured both horizontal and vertical lines. Because of astigmatism they’re usually slightly different (look at the center yellow numbers – in the center this camera-lens measured 2935 on vertical lines and 2769 on horizontal. You can make an argument for reporting vertical or horizontal resolution only, just the higher of the two, or the average of the two. We use the average, but I’m not sure what everyone else does, so vertical versus horizontal resolution can be another source of variation.

The final argument concerns what is the corner value. Notice the corner horizontal and vertical resolution measurement areas are different in this example because this chart isn’t set up perfectly (it’s from a medium format camera with the wrong format size for this chart). My takeaway point is you can’t always measure the absolute furthest corner with this method. The measurement is some distance from the corner and that may vary between testers slightly, depending on which chart they use.

These Systems Test Camera-Lens Combinations

I think everyone knows this, but maybe not. You can’t compare a two-year-old-test done with a Nikon D700 (or Canon 5D) with a newer test of the same lens done on a Nikon D800 (or Canon 5DIII). Change in camera resolution equals change in system resolution equals different numbers. Even if resolution is about the same, different microlenses on the sensor might make a difference in edge and corner readings.

Every Lab is a Bit Different

One day we started testing and 12 lenses in a row failed to meet expected resolution. We figured maybe something odd was going on and investigated. It turns out people at the other end of our building were tearing up concrete floors. We couldn’t hear them, but the vibrations were screwing up our tests.

We were doing quality control checks on lenses we already had numbers for, so we knew something was wrong. But if that was the first day we were testing that lens, or if I was a reviewer testing my only copy of the lens, I might have just decided the lens sucked.

We had a similar phenomenon occur when we changed lighting systems from fluorescent to tungsten. It changed our values slightly.

The takeaway message is everyone’s lab is slightly different. Even with the exact same camera and lens they will have slightly different results. But no two testers ever have the same copy of the camera and lens. Which brings up the second source of variation. (Nice segue, isn’t it?)

The Single Copy Phenomenon

If you’ve ever read anything I wrote, you probably already know this. If not, here’s an absolute reality you need to digest. Every copy of lens X is just a little bit different from every other copy. Every copy of camera Z is just a little bit different from every other copy. There are manufacturing tolerances for such complex devices that are unavoidable at any price.

If you can’t accept it, you definitely need to stop pixel peeping. You’ll go insane. If you want to say, “For $2,000 every lens should be perfect” then you are very naive. We have $50,000 cinema zooms and they are all slightly different, too. In fact, at the very highest levels, technicians will hand calibrate each $50,000 lens to the $100,000 camera because there is still variation.

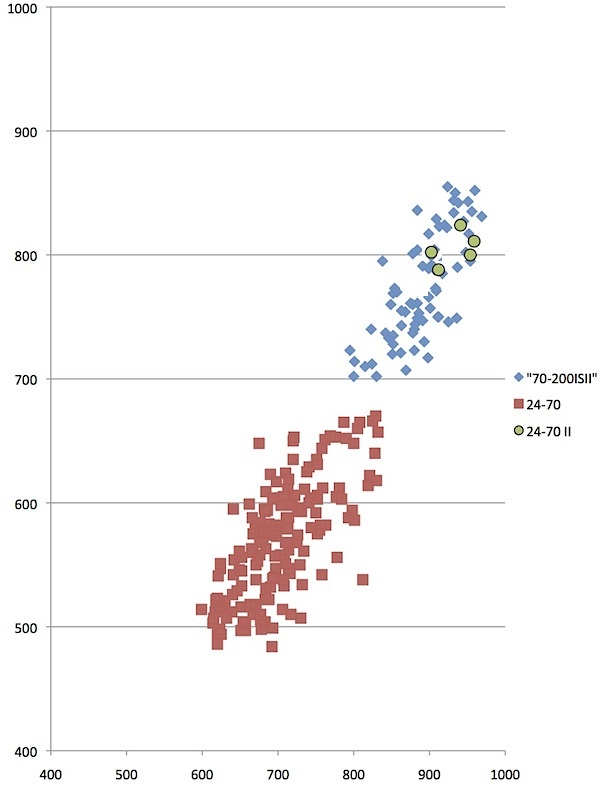

But let’s look at how much this variation affects numbers with some real-world samples. Here’s a chart I used in another article about the Canon 24-70 f/2.8 Mk II shot at 70mm and compared to the original version and the 70-200 f/2.8 IS II. The table presents the average (mean) Imatest results for peak value and overall value (average MTF50 at 13 points). It looks nice and simple, doesn’t it? That’s why I presented it that way, because that’s what people want.

Ctr MTF50 Avg MTF50

70-200 f2.8 IS II 885 765

24-70 f/2.8 705 570

24-70 f/2.8 Mk II 950 809

Below is the actual data used to obtain those numbers (well most of it, this graph only has a subset of the 70-200 and 24-70 numbers). These are the individual Imatest measurements for around 75 copies of the Canon 70-200 f/2.8 IS II, around 120 copies of the Canon 24-70 f/2.8, and exactly 5 copies of the Canon 24-70 f/2.8 Mk II.

The horizontal axis is MTF50 at the center point, while the vertical axis shows average MTF50 measure at 13 points like the illustration above. It’s not nearly as simple, clean, or easy-to-read as the table of average (mean) numbers. What can I say with absolute certainty? At 70mm you’re never going to find a 24-70 Mk I that’s as good as either a 70-200 f/2.8 IS II or a 24-70 f/2.8 Mk II.

The number in my table says the 24-70 Mk II is ‘better’ than the 70-200 IS II, because the mean value is slightly higher. It should be pretty obvious, though, that if a reviewer tests one copy of each, there’s a good chance his 70-200 IS II may be better than the 24-70 Mk II he has. I’ve certainly got some 70-200 IS II lenses in stock that are a bit sharper (at least with numerical measurebating) than any of the 24-70 Mk IIs we have. Most of them aren’t, though.

It doesn’t take much imagination to understand that when we test another 50 copies of the 24-70 Mk II the average (mean value) might be different than the first 5 copies. Until I test a lot more 24-70 Mk II samples, though, I won’t have a really accurate idea of the range of that lens.

Early reports from reviewers seem to indicate there might be a lot more variation in the 24-70 f/2.8 Mk I than I thought at first. Since all 5 of my samples were very close in serial number, it might have given me a false sense of security about low variation between copies.

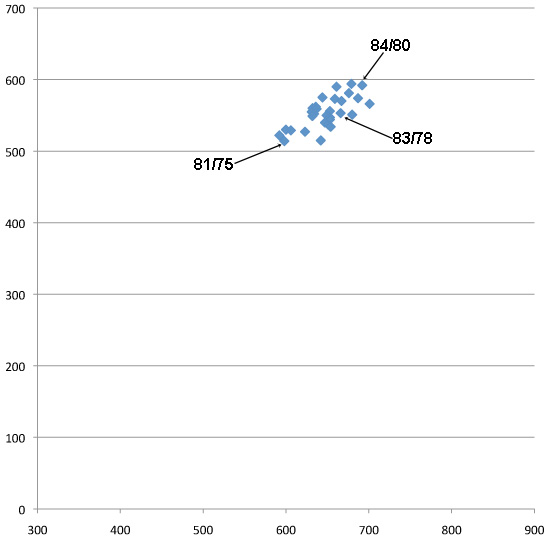

MeasureBating

The lenses in the graph below are all ‘within normal range’. (This is a prime lens, so the variation is smaller than with a zoom.) The numbers pointing to the best, worst, and one of the middle copies are SQF values. If the SQF value is within 5, you probably can’t tell the difference in a photograph. The MTF 50 for the best lens is 690 / 590. For the worst one it’s 585 / 510. That sounds hugely different.

If I used SQF numbers instead (84 / 80 compared to 81 / 75) it doesn’t sound nearly as impressive, although one lens still has better numbers than another. But if I took real-world photographs you probably couldn’t tell the difference.

It doesn’t make the numbers less real. Geeks like me can dance celebrations to the triumph of the lens designer when he hits big numbers. But reality is the difference we’re measuring, while real, may be so small that it can’t make a noticeable difference in pictures.

In the real world the difference in how well the camera hit focus, how correct exposure was, if there was a tiny bit of movement creating blur, and a zillion other things make more difference than the difference between those two lenses.

So Is All this Measurement and Reviewing Entirely Worthless?

No, not at all. But any single reviewer’s or tester’s comments (including mine) must be taken with a grain of salt. When 4 or 5 reviews are all roughly the same, you probably are getting a reasonable overview about the lens.

When 6 reviews say one thing and two say something different, don’t do the internet thing and decide two of them are lying or incompetent. You might miss some important information that way. Look more carefully and you might find the 2 reviewers were looking at something different than the other 6.

The Zeiss 25mm f/2 lens provides a great example. Imatest people, like myself, tend to rave about how well the lens resolves. We are all testing it at 6 to 12 foot shooting distances. People who shoot landscapes talk about the lens having soft corners when focused at infinity. Guess what? Everybody is right. They’re just telling you two different things about the lens.

Of course even the most careful reviewer will make a mistake sometimes. (I’ve certainly made mistakes and I suspect everyone else in this field has, too). They might have gotten a bad copy — it happens and it seems to happen more during the first shipment of a lens or camera.

They might have had very high expectations and the lens didn’t meet them. Or they might have had very low expectations and the lens exceeded them. I did just that back when Nikon released the 24-120 f/4 and 28-300 VR lenses. There’s no question the 24-120 is the sharper lens and had the better MTF numbers when I tested them. But I waxed poetic about how great the 28-300 was because I just I expected it to suck like every other superzoom. When I found it was pretty good, I lost my mind a bit.

For all those reasons, nobody should ever buy a lens based on a single review. But after looking at 5 or 6 you usually get a pretty good idea of how good or bad a lens is.

And let’s face it. We all know early adapters pay a price and are doing some beta testing anyway. If you’re waiting for the first review to come out so you can decide if you want to preorder that lens TODAY, just go ahead and order it. You know you’re going to.

For Those of You Certain THE MAN is Buying Great Reviews!

I love a good paranoid rant as much as the next guy. And I can’t say it never, ever happens because I don’t know everything. But I seriously doubt it happens.

I know a lot of reviewers pretty well. Every single one I know spends hours and hours worrying about the accuracy of their methods, the accuracy of their results, and making sure they don’t say more than they know. They got into this field because they’re geeks, mostly, and they love doing this stuff.

Review sites that give bad information don’t tend to grow very much or survive very long. Most of the successful ones have large websites that generate lots of traffic or subscriptions. It would take a very large payment for them to put their years of work establishing credibility at risk.

Even more than that, I think a camera company would be pretty insane to ever risk someone going public that they received kickbacks or payoffs. Think about it. A company pays Joe $10,000 to write a stellar review. If Joe was really smart and unethical he’d document it, call them back in 6 months and demand 10 times that much to keep him from going public with his documentation.

Are there more subtle influences? Sure. Getting a lens or camera to test before anyone else gives a reviewer a head start and some traffic. But you have eyes the same as I do. The largest sites get the prerelease cameras and lenses and not the smaller guys, usually. The camera makers are going to supply the people with the most readers whether they say nice things or not.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

September 2012

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Mark Blum

-

xrqp

-

xrqp

-

xrqp

-

Max

-

Gert Weber

-

Nikola Runev

-

Bob

-

Randy

-

Jim Thomson

-

Nicholas Condon

-

Dieter

-

Dieter

-

Dieter

-

Joachim

-

Aaron

-

Chas

-

Nate

-

Justin