History of Photography

Six Degrees of Charles Darwin, and Rejlander’s Last Laugh.

Six Degrees of Charles Darwin

Note: For those offended by such things, there is a small photograph reproduced below that has artistic nudity.

You’re probably familiar with the film-buff game, Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon. If not, basically you name any individual who is associated with movies and you should be able to connect that person to Kevin Bacon using no more than six individuals (usually less). It’s even built into Google’s search engine, you simply type “Bacon number” followed by the person’s name. For example, Barack Obama’s Bacon number is two: Obama and Tom Hanks are in The Road We Travelled, Hanks and Bacon were both in Apollo 13.

If you’re a photo history buff, you can do the same thing with Charles Darwin for almost any photographer of significance in 19th century photography. For example, Chevalier, who made the lenses for the original Daguerrotype camera, has a Darwin number of 4: Chevalier made lenses for Daguerre. Sir John Hershel showed Daguerre how to make his images more permanent using sodium thiosulfate. Sir John and Darwin worked together advocating Darwin’s Theory or Evolution and Darwin refers to him in the opening line of The Origin of Species. Similarly, Sir Humphrey Davy has a Darwin number of 2: Darwin’s Uncle was Thomas Wedgewood, who along with Sir Humphrey Davy, made the very first images.

It may seem surprising at first, but really it’s not. Darwin probably had his portrait taken by every well known photographer of the day. He made even more connections to the photography world because it was Darwin who largely legitimized photographs as the documentation and illustration for scientific books. Before that time, a well recognized scientist was expected to provide excellent drawings or engravings for his publications. Photographs were used to document places and scenes, but infrequently for scientific work.

Darwin chose to use photographs for the documentation of his book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals published in 1872. He had many reasons for doing so, but probably first among these were that one of his more respected adversaries, Professor Agassiz, planned to use photographs in a book refuting evolution. Agassiz massively shot himself in the foot on that plan, as we’ll discuss in a bit, but Darwin still liked the idea.

The best part, though, is the story of one photograph in the book, and the photographer who made it. The photographer, oddly enough, was Oscar Rejlander who was quite controversial in the day because he heavily modified his negatives to achieve the artistic effect he sought in his prints. That Darwin would choose him as the primary photographer documenting a scientific book was surprising. That Rejlander played a joke on the photography world while doing so should not have come as a surprise at all.

Darwin’s Antagonist

Darwin’s theories still are criticized by a few people today (Which we aren’t going to do in the comments of this article, OK?). In the 1860s, though, the criticism was constant, personal, and strident. In an era when gentlemen usually politely disagreed with their ‘respected opponents’, the evolution debate was more like a Fanboy argument in an online forum. Critiques were vindictive, pointed, and used facts only when personal insults weren’t available.

One of the main opponents of evolution was Harvard Professor Louis Agassiz. One of the more famous scientists of the time, he was a geologist, paleontologist, and biologist. He had issued the authoritative Nomenclator Zoologicus, a classification of all genus and species, and was the first scientist to recognize the past ice ages of the earth. Despite their difference of opinion, Darwin respected him as a scientist.

Agassiz did not argue that Darwin’s observations regarding differences in species were wrong, he accepted those as fact. He believed, however, that the Creator had formed each species ideally for its environment and this, not evolution, accounted for the differences Darwin had observed. Agassiz had also observed that when animals breed outside their species, the offspring are often either sterile, like mules, or could not find a mate because they looked different. (This happens with various species of butterflies, for example.) For this reason, he felt evolution as theorized by Darwin was impossible.

His arguments were persuasive, and he convinced a wealthy Bostonian businessman, Nathanial Thayer, to fund an expedition to document the thousands of animal species in the Amazon basin. He thought he could demonstrate theses species had not changed over the ages, proving evolution false, and planned to use photography to document his observations.

Agassiz did superb scientific work on the Thayer expedition, cataloging some 34,000 specimens. The photography aspect, though, contained some pretty bizarre stuff. Agassiz took hundreds of pictures, most of native women’s breasts. He then compared these to the breasts of fine Greek and Roman statuary, claiming he could determine race on this basis (1, 2, 3, 4).

Needless to say, his book A Journey in Brazil, was not the evolution killer he had promised. The photographic documentation that had interested Darwin never appeared. The images, apparently lost for decades, are kept locked in Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography today, and few of the images have ever ben released.

Darwin’s Photographs

Darwin had become fascinated by the fact that “…the young and the old of widely different races, both with man and animals, express the same state of mind by the same movements.” He felt the experession of emotions represented instincts, and that these instincts might be similar between humans and various animals. Having heard about Agassiv’s plan to use photographs for documenting his book, Darwin wanted to do the same thing for The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

Darwin spent years collecting and studying photographs and paintings of the various emotions. He corresponded at length with zookeepers, photographers, illustrators, and even the directors of mental institutions (he felt mental patients exhibited ‘unrestrained emotions’ that would make good examples), obtaining photographs and illustrations to use in his book. He did obtain several usable photographs, and, of course, a lot of connections with the photographic community that help make 6 Degrees of Darwin so easy to play.

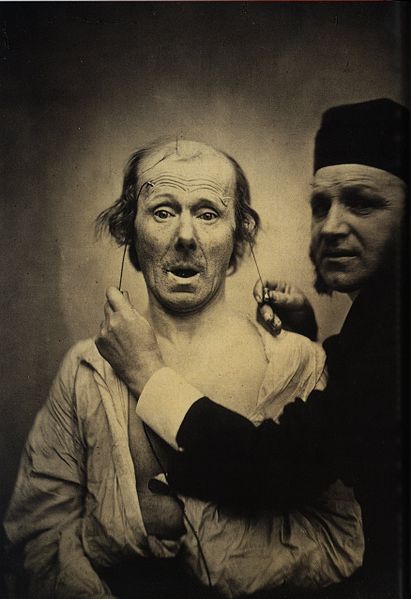

Among the most interesting were photographs taken by French neurologist Guillaume Benjamin Amand Duchenne (who discovered among many other things the type of muscular dystrophy named after him). Duchenne had discovered that by applying small electrical currents over the muscles of the face, he could create any type of facial expression.

While this type of human experimentation would be rather unnaceptable today, Duchenne assures us the subjects felt ‘only the slightest discomfort.’ Duchenne’s method, in addition to obtaining whatever expression one wished to reproduce, would maintain that expression for as long as the current was applied. This was an important benefit in an era when taking a photograph required several seconds of exposure.

- Guillame Duchenne applying ‘Faraday current’ to create an expression in an experimental subject. Courtesy Wikepedia commons.

- A more complex application of electrodes. This is perhaps the ‘slight discomfort’ of which Duchenne spoke. Wikepedia commons

Darwin was quite pleased to have such good photographs of emotion, but felt that, even in his day, people might just be just a bit distracted by the electrodes and wires in the photographs. After all, the book was discussing the expression of spontaneous emotions and the photos above don’t look all that spontaneous. Darwin finally decided it might be better to make them engravings and leave out the electrodes and stuff.

- The above images as used in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

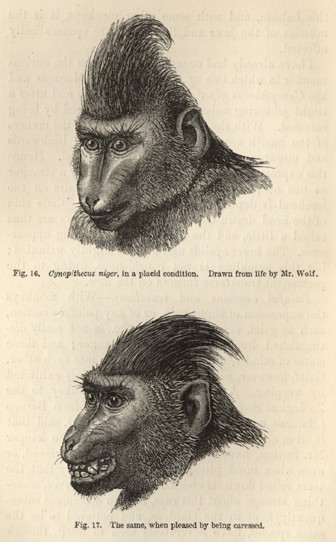

Darwin also used engravings for most of the animal expressions in the book. That’s understandable since trying to get an animal to hold an expression for a 2 or 3 second exposure isn’t too likely. Unless the expression is ‘asleep.’

I suppose he could have asked Duchenne to do his electrode thing with some animals. I get tickled just thinking what the lab would have looked like, oh, about 30 seconds after he decided to apply that current to a gorilla.

- Illustrations from The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Engravings by Wolf.

But less than a year before publication, Darwin still did not have what he felt were acceptable photographs to illustrate most human emotions. He discussed the project with a number of the day’s photographers, but they weren’t able to deliver the results he wanted.

Thence Came Rejlander

In 1871 Darwin settled on the well-known photographer, Oscar Rejlander, to obtain photographs for the remaining illustrations. The connection between Darwin and Rejlander was obvious. Darwin often visited photographer Julia Margaret Cameron and considered her a good friend. Cameron was a student of Rejlander’s and recommended him.

The choice, though, seems rather odd because Rejlander was known as an ‘artistic’ photographer who posed and modified his images. Critics of the day felt photographic images should be ‘straight from the camera.’ Rejlander strongly disagreed. He felt photography was art and any means that allowed artistic expression was fair.

His most widely known photograph,Two Ways of Life, had been denied exhibition at the Photographic Society of Scotland because they considered it a false photograph — the print was made by superimposing around 30 negatives. The draperies, for example, are actually the edges of a tablecloth in his studio.

- Two Ways of Life. Rejlander, 1857

His best selling photograph, Poor Jo, seemed to be a spontaneous photograph of a homeless child in London. It actually was a staged photo of a model taken on the stairs in Rejlander’s studio.

- Poor Jo. Rejlander, 1864.

By the late 1860s, Rejlander’s reputation had suffered under the constant criticism. He maintained good cheer and worked diligently, but his images no longer sold well and he was struggling financially.

But he had worked for some years capturing emotional expressions, especially of children, so he had a large number of stock photos already available as examples. There was also the fact that Rejlander was exceptionally good and Darwin had publication deadlines approaching.

The bottom line is Rejlander delivered and the book contains a number of is images, demonstrating exactly the emotions Darwin wanted demonstrated. In fact, 19 of the 30 photographs in the book are by Rejlander. Several of them are actually self-portraits of Rejlander acting out various emotions.

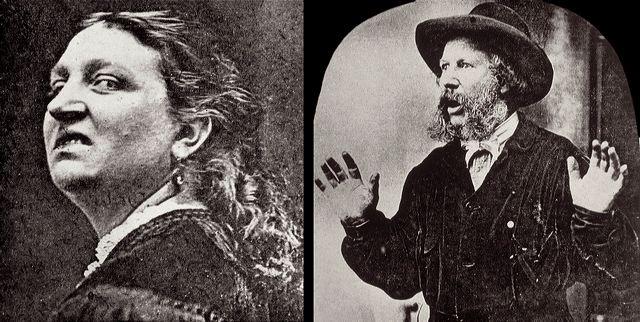

- Images from The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals. Rejlander, 1872. Rejlander is actually the subject on the right, his wife Mary on the left.

Rejlander’s images were critically acclaimed and the publicity the book brought him helped him stay solvent in his few remaining years (he died in 1875). Actually, the images were more successful than the book. Rejlander sold over 100,000 prints of the images he made for the book, compared to the 7,000 books sold in the first edition.

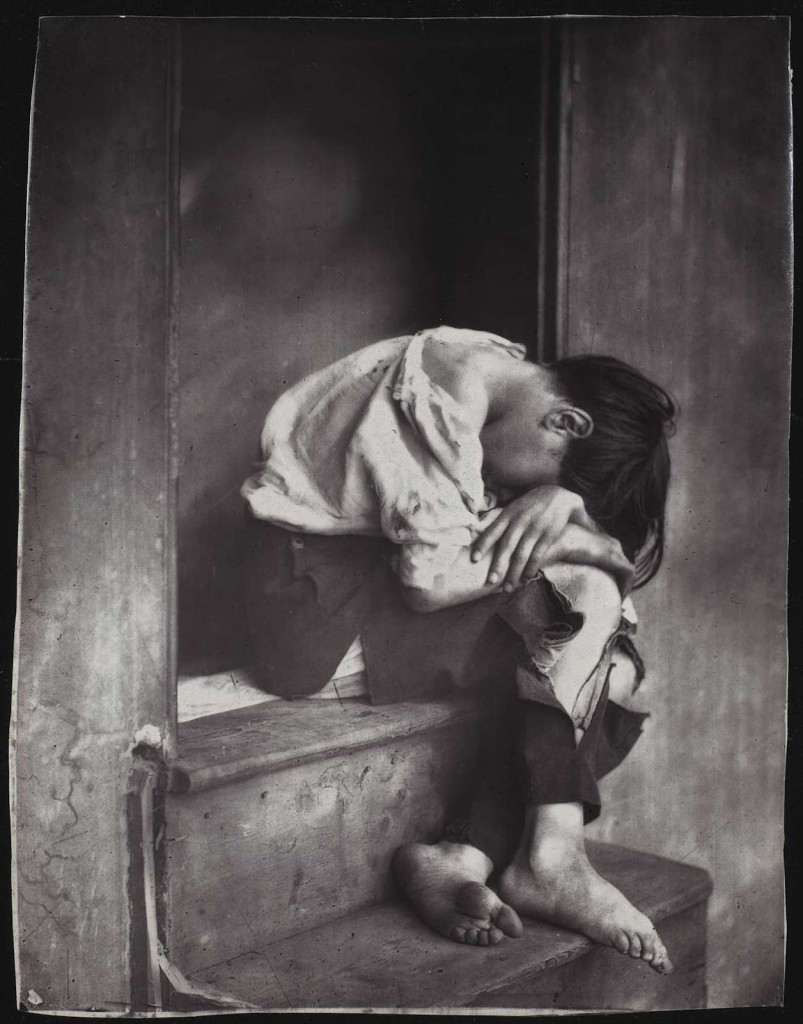

Ginx’s Baby

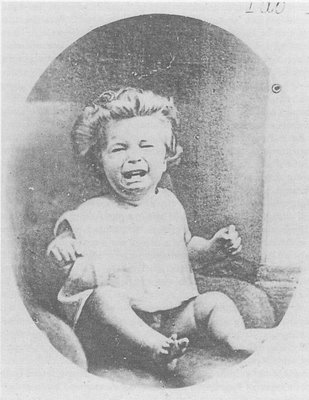

On of Rejlander’s images, in particular, generated rave reviews. It illustrates a crying child and was hailed as one of the first “momentary” images ever made. Critics, including many who had been unkind about Rejlander’s work, raved about the amazing quality of this image.

- Crying child. Rejlander. Later known as “Ginx’s Baby”.

The picture became so famous that Rejlander sold thousands of prints in different formats, making it his most profitable photograph, ever. Part of the reason for the fame was another book, Ginx’s Baby. His Birth and other Misfortunes: A Satire by Edward Jenkins. The book was immensely popular at the time and Rejlander’s photograph appeared on the cover of some versions of it.

Rejlander, ever the jokester, later mimicked the picture showing that really laughing and crying were very little different. He even made a stereoscopic card of himself next to the picture, making a similar expression of either laughing or crying, which he sent to Darwin.

- Rejlander laughing and crying beside “Ginx’s baby”. Stero card, 1872 or 1873.

Rejlander made another double print near the end of his life, Rejlander Introducing Mr. Rejlander. The images show him on the right standing in front of an easel pointing to himself on the left dressed in the uniform of the Artist’s Rifles, a volunteer military brigade of which he was a proud member (he asked to be buried in his uniform).

- Rejlander Introducing Rejlander. 1873.

But there’s a bit more to it. The Rejlander standing on the right is wearing the same clothing he did when posing for some of the images in The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. The easel behind him is displaying Ginx’s Baby. If you look carefully, you’ll notice ‘military’ Rejlander is standing on the same steps used in his posed photograph Poor Jo.

Rejlander seems to be celebrating his two best selling images. But it turns out there was a bit more to it than that. Just as Poor Jo was an image supposedly showing a homeless child in London, it turns out Ginx’s child is an image supposedly showing a photograph.

The original photograph, maintained in Darwin’s archives, was taken from a further distance and the child is much smaller in proportion to the image. In all likelihood, Rejlander had to use a fairly wide angle lens to get a short enough exposure time. Cropping the image for the Heliotype process used for the book would have left it lacking significant detail.

- Original photo of Ginx’s Baby. Rejlander. 1871?

Rejlander was a trained artist and draftsman. He apparently used a technique he’d used several times in the past: he taped the image to an otherwise blacked out window, put his view camera in front of it, and used the camera’s lens to project the image on a paper. He then outlined the projected photograph, filled in the outline with chalk, and finally took a close-up photograph of the resulting painting.

The image remains true to life, although Rejlander added a chair rather than the toddler-holder-on-a-table seen in the original photograph. Darwin’s notes show clearly that Rejlander had sent the final image labelled ‘photograph of chalk drawing.’ A few early copies of the book contained the original unretouched photograph, but the vast majority have the photograph of the drawing. It has been speculated that the original image reproduced so badly that the photo-drawing was substituted for it very quickly. In either case, however, the text in the book labels the image as a photograph.

This may have been an accident oversight following the change, or simply Darwin’s judgement call (he felt the drawing was faithful to the photograph), or the publisher not wanting to reprint the text associated with the photograph. But whatever the reason, the image was clearly labeled as a photograph in the book and neither Darwin nor Rejlander corrected any of the many rave reviews of the image that occurred after the book’s release.

Certainly Rejlander, who had received so much criticism for his ‘obviously retouched and staged’ photographs probably loved the fact that the critics didn’t have any questions of the authenticity of this image. And it was also incredibly well done. The original chalk drawing was in the collection of the Royal Photographic Society for years and was labelled as a hand-coloured photograph. If not for the original image and final images labelled as ‘photograph of chalk drawing’ being found in Darwin’s archives, it might never have been discovered.

It should also be noted that Rejlander became ill soon after the book was published and died just a few years later. Being unable to work and making significant money for the first time in his life, one can understand he was not too eager to correct the public’s perception that it was an actual photograph.

I wonder, though, if his Rejlander introducing Rejlander photograph was his way of leaving a message for the critics when they finally discovered the truth.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

November, 2012

Note: If you don’t mind reading some 1860s prose, Rejlander’s article linked below is a marvelous defense of art in photography.

Other References:

Rejlander, Oscar: An Apology for Art Photography. Read at a meeting of the South London Photographic Society, 1863.

http://www.psiquifotos.com/2009/04/56-el-ginxs-baby-de-reijlander-y-darwin.html

Prodger, P. Darwin’s Camera. Art and Photography in the Theory of Evolution.Oxford University Press. 2008

Lenoir, Timothy: Scientific Texts and the Materiality of Communication. Stanford University Press. 1998.

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Johne593

-

Ricardo

-

winsor

-

simon

-

Shawn

-

Nikhil Ramkarran

-

Joel Dowling

-

Nqina Dlamini

-

A

-

Siegfried