History of Photography

And Edgerton Said, “Let There Be Light.”

The more I learn about the history of photography, the more I come to realize that just about every important advancement since 1850 has its roots in photography. The 8 hour workday, paid vacations, and employee stock options? A photography manufacturer started them. Telegraph? A photographer invented it. Synthetic cloth was just an offshoots of photographic chemicals, and the development of plastics was funded by the sale of a photographic patent. In my last article, we even saw how toy trains owed their start to photography.

“Don’t make me out to be an artist. I am an engineer. I am after the facts, only the facts.” – Harold Edgerton

Today’s subject was the most prolific photo-inventor, ever. He had dozens of patents, and his patents generally were for groundbreaking new technology, not just minor refinements. No one, other than maybe Thomas Edison, worked in such a wide variety of fields. He won the Howard N. Potts and Albert A. Michelson Medals for scientific achievement and the National Medal of Science. He wrote dozens of scientific papers.

Best of all, he was a photographer before he ever invented anything, and remained a photographer his entire life. His images were included in the The Museum of Modern Art’s first photography exhibit, won a Bronze Medal from the Royal Photographic Society, and a short film won an Academy Award. He published books of fine art photographs.

He wasn’t just a great photographer and scientist. He just oozed all-around awesomeness. For example, when asked to provide a picture of himself, he created “Self Portrait with Balloon and Bullet.”

- “Self Portrait with Balloon and Bullet” Edgerton, 1959, Harold E. Edgerton Trust. Notice the seemingly casual pose includes putting his finger in his right ear to protect from the noise of the gun in the foreground firing the bullet seen to the right.

As I wrote this I couldn’t help paraphrasing the old Chuck Norris joke: Harold Edgerton slept with a night light. Not because he was afraid of the dark. Because dark was afraid of Harold Edgerton.

Some of his actual accomplishments sound like Chuck Norris jokes.

- When someone asked Edgerton to take a picture of a bullet passing through a playing card, Edgerton simply asked, “What part of the bullet? Front? Middle?”

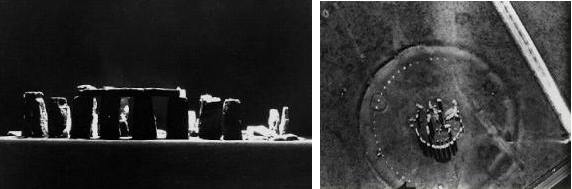

- When British scientists said strobe flashes could not possibly be used for war reconnaissance photos, Harold Edgerton photographed Stonehenge on a moonless night. From 10,000 feet.

- Back when biologists argued about how hummingbirds could possibly fly, Harold Edgerton not only showed how they flew, he showed that their wings beat 70 times per second.

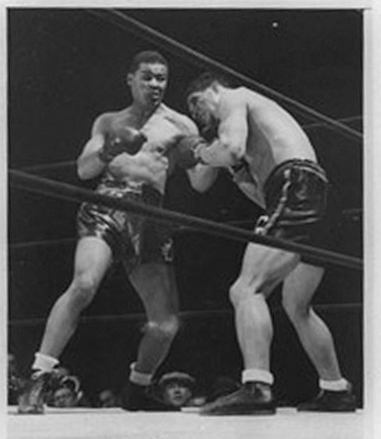

- When Kodak told him there was no practical use for strobes in photography, Harold Edgerton photographed a boxing match at night and wired the photos to every newspaper in the country.

- When Jaques Cousteau wanted a flash to take pictures in deep, dark water, Harold Edgerton made the flash. And then invented side-scan sonar so Cousteau could find things underwater to take pictures of.

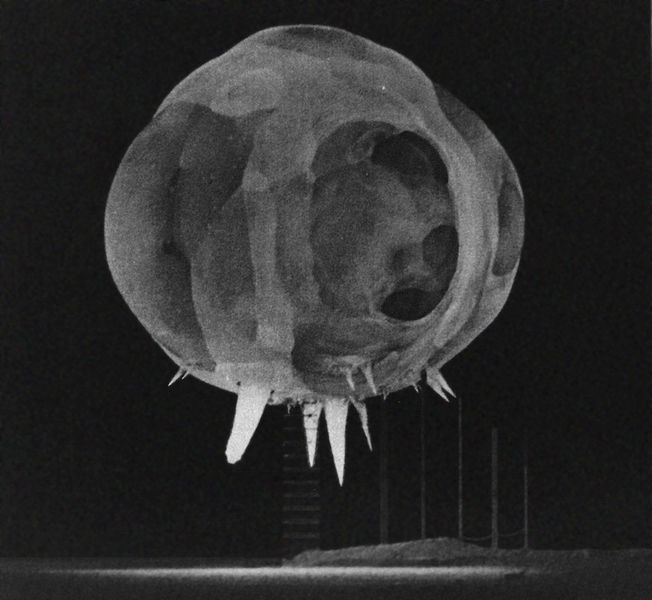

- When the scientists at Los Alamos finished designing the first atomic bomb, they realized they had no electrical capacitors powerful enough to trigger it. Harold Edgerton loaned them some. Then he designed a camera that could take pictures of the explosion before it had spread 100 yards wide, so they could see how it worked.

The number of Edgerton’s accomplishments makes this article rather long. But if you have any Geek-history (is Geekstory a word?) interest at all, I think you’ll enjoy reading about the ultimate photo-inventor.

The First Electric Flash

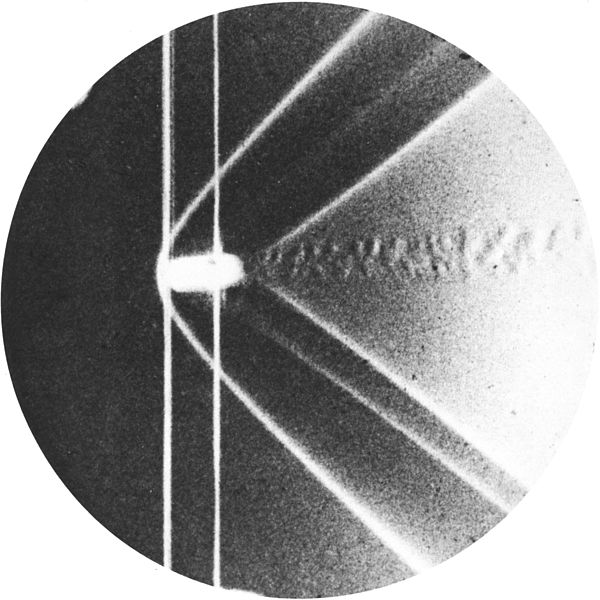

Way back in the 1850s, Fox-Talbott had used an electric arc lamp as a light, and in 1886 Ernest Mach (of Mach number fame – the ratio of an object’s speed to the speed of sound) used a collimated electric arc light powerful enough to let him photograph the shock waves created by a bullet in flight.

- Shock waves from a bullet in flight. Ernest Mach. John D. Anderson, Jr., Modern Compressible Flow: With Historical Perspective, (New York, NY. McGraw Hill, 1990), pp. 92-95.

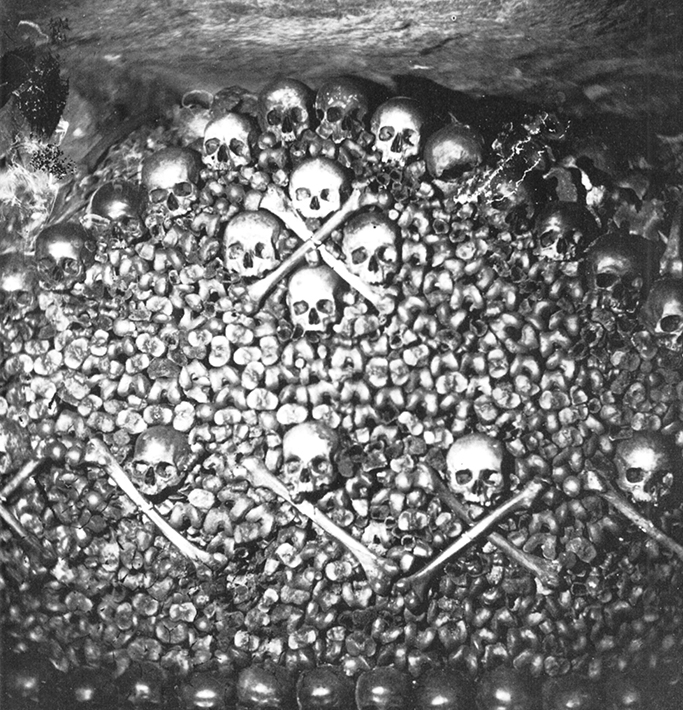

Gaspard-Félix Tournachon (aka Nadar) used battery powered electric arc lights to photograph the underground catacombs of paris in 1863.

- Catacombs of Paris, Felix Nadar, 1861.

Electric arc lights had some major drawbacks: they were huge, expensive, used an enormous amount of electricity, and were incredibly loud (it is said when Mach took his photographs no one could hear the gunshots because of the much louder sound of the arc lights). For all of these reasons they were rarely used for photography. Plus they weren’t nearly as fun as setting off a pile of flash powder.

The Invention of Strobes

“If you don’t wake up at 3:00 AM to start testing your ideas then you are wasting time.” Harold Edgerton

Harold Edgerton grew up in Aurora, Nebraska basically interested in two things: photography and electricity. His uncle Ralph taught him photography. He worked summers for the Nebraska Power and Light Company learning about electricity. He studied electrical engineering at the University of Nebraska and then applied to graduate school at M. I. T. which he’d heard of but knew little about. He knew another Aurora High School graduate had studied at Harvard, so he asked him about M.I.T. The Harvard graduate told somewhat snidely that “MIT only takes smart students.” Edgerton said that from that point on, “I have always disregarded the opinions of Harvard students.”

At MIT, Edgerton wanted to study the effect of current surges, like lighting strikes, on electric motors. Because the motors spun so rapidly, this was nearly impossible to do, but Edgerton noticed that the mercury vapor tubes in the electronic apparatus he used to send current surges to the motors gave off a bright light during each current surge. If he turned off the other lights in the room this ‘strobe effect’ made the motor appear to stand still, since the light flash and motor revolutions were in sync.

Using his photography background he modified the tubes to give brighter flashes that were as short as 10 microseconds (that would be like setting your camera to a 1/100,000 exposure). Photographing the motor by this flash gave such a short exposure time that he was able to freeze the motion of the motor — and just about anything else he was interested in.

Edgerton realized he could also shoot movies this way. Movie cameras of the day shot 24 frames per second, but Edgerton removed the shutters, added special motors and pulled film through at 100 feet per second (2,000 to 6,000 fps), exposing the film simply by the stroboscopic flash. Edgerton’s doctoral thesis consisted partly of a silent film demonstrating the ‘stroboscopic’ technique. You can see it HERE.

Development of Strobes

Edgerton’s initial light was from a mercury-arc rectifier, a tube that was used to convert AC current to DC current. While far better than an arc light, and able to create a flash as short as 10 microseconds, it had some drawbacks. Mercury arc lamps don’t work well when cold and are large, making it difficult to fit a reflector around them.

- Probably the last working mercury-arc rectifier. Blosenbergturm, Switzerland, 2008. I’m told for the last few decades their major use has been as props in science-fiction movies. How cool is that: something designed in the 1920s is used as a prop for movies about the future.

In 1930, Edgerton created an entirely new type of lamp using Argon gas instead of Mercury vapor. This was much smaller and more efficient, worked fine when cold, and could easily be mounted in front of a reflector. A decade later he created flashtubes using Xenon gas, which gave a more ‘white’ light spectrum. Xenon tubes are what you are using in your flash today.

The electronic flashtube is a simple thing. It consists of a glass tube (the type of glass is chosen to pass certain wavelengths of light better than others, which is why some flashes appear ‘warmer’ of ‘cooler’ than others) filled with Xenon gas with an electrode at each end. Outside the lamp a capacitor charges from the lower current supplied by the batteries (this is what you are waiting on between flashes), then sends current through a transformer that jumps the voltage up, sending a pulse of several thousand volts through the flash. This converts the gas to an ionized plasma which gives of photons (light) as it returns to a nonionized gas phase. Flashtubes are amazingly efficient, converting as much as 50% of the electricity that enters them into visible light.

By 1935, General Electric had licensed Edgerton’s patents to produce the Strobotac, a portable plug in strobe that is actually still used today for industrial applications. He approached Kodak about the potential of electronic strobes in photography but they weren’t interested, saying they doubted that there would be a market for more than 50 units. Edgerton didn’t argue, he simply took his equipment to several major sporting events and used his strobes to capture action shots that weren’t possible with any other type of lighting — try igniting your flash powder to catch the moment a punch impacts.

- Louis vs Conn, 1941, Edgerton. http://webmuseum.mit.edu/ This was the first photograph of a night sporting event ever ‘wired’ to papers across the country.

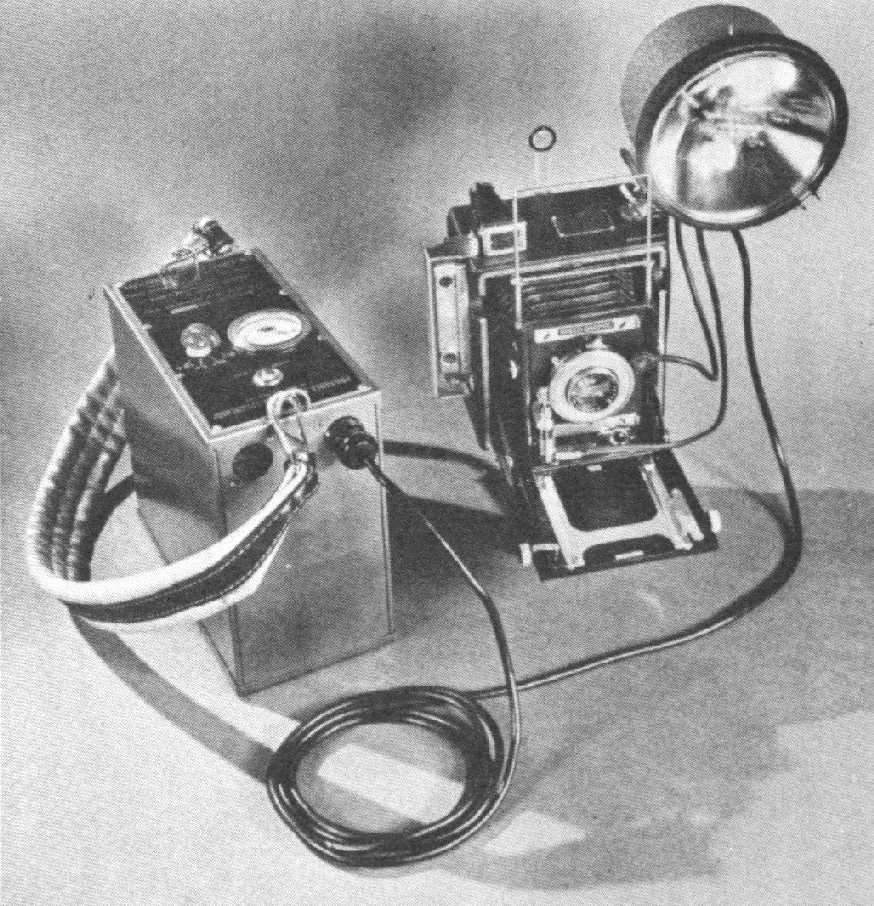

As I’m sure Edgerton knew it would, the Kodatron Electronic Flash Unit became available in fairly short order. Electronic flash was being used in professional photography by the 1950s, but it really wasn’t until the 1970s that it began replacing flash bulbs and flash cubes for widespread use. Today, flashtubes come in all shapes and sizes, from the small, straight tubes in your on-camera flash, to larger circular tubes in most strobes, to 6-foot long tubes used to ignite industrial lasers.

- Kodatron Flash Unit, circa 1941. MIT.edu

Even if Edgerton did nothing but invent the electronic flash, his place in the history of photography would be secure. But he did a lot more than that.

Photography

Edgerton, like Muybridge before him, became fascinated in using his new toys to freeze fast motion. He made a lot of Muybridge-like images, although his extremely short exposure times showed things that would never have been visible to Muybridge.

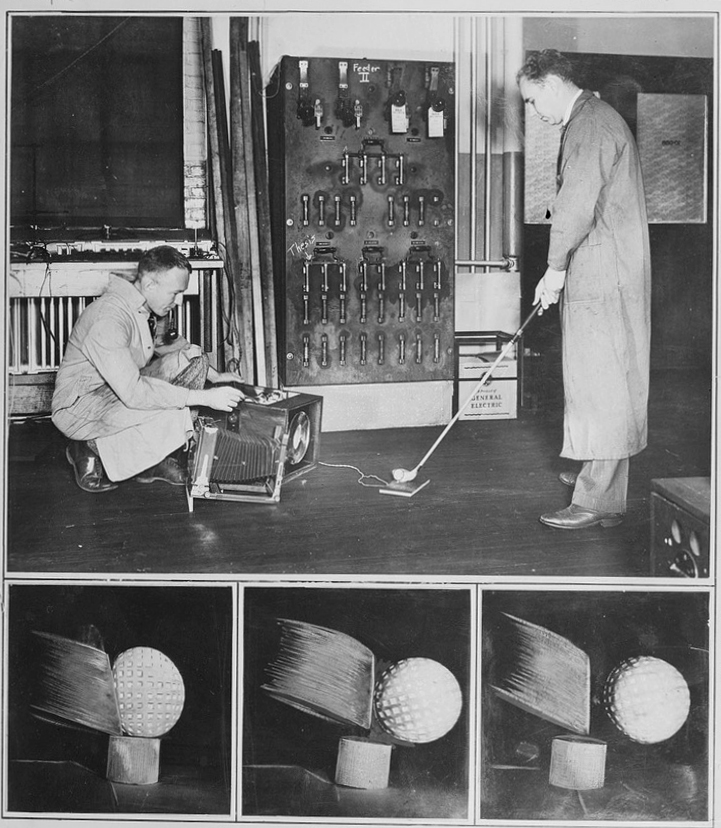

- Image showing Edgerton’s setup for images of striking a golf ball, and several images at the moment of impact.

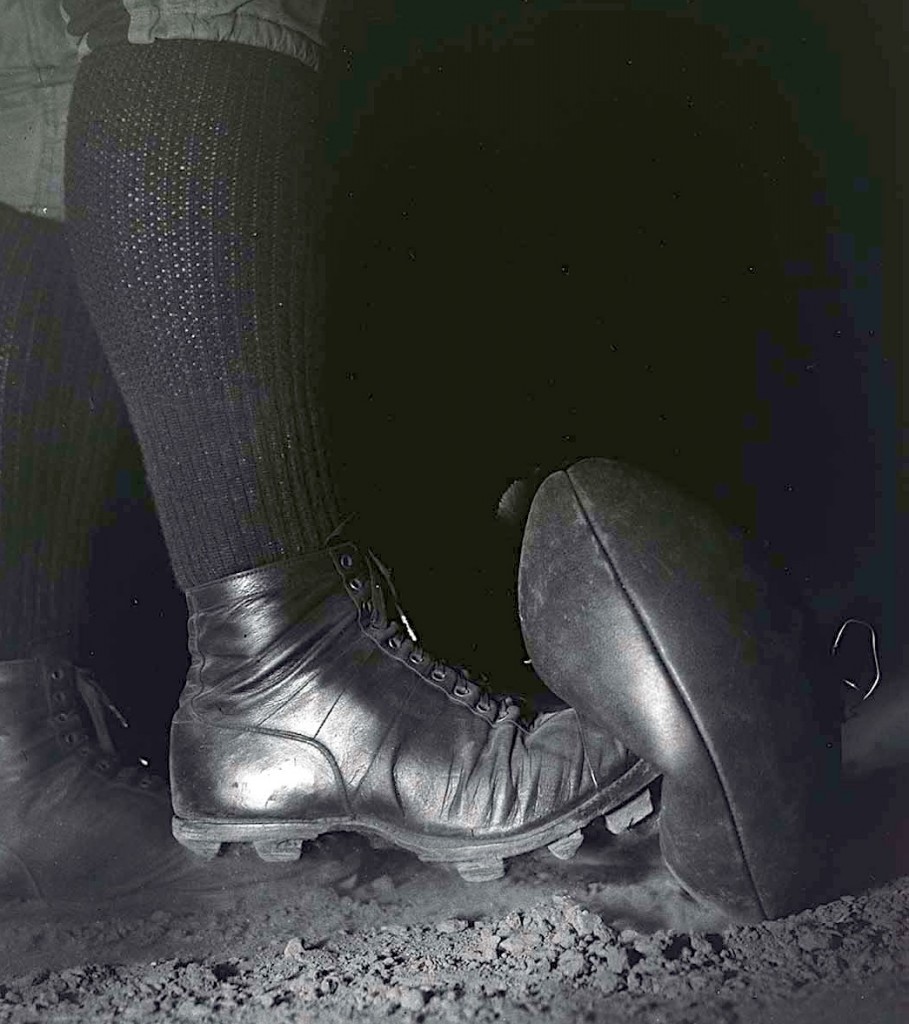

- “Football Kick” by Harold E. Edgerton, 1934, Smithsonian Museum

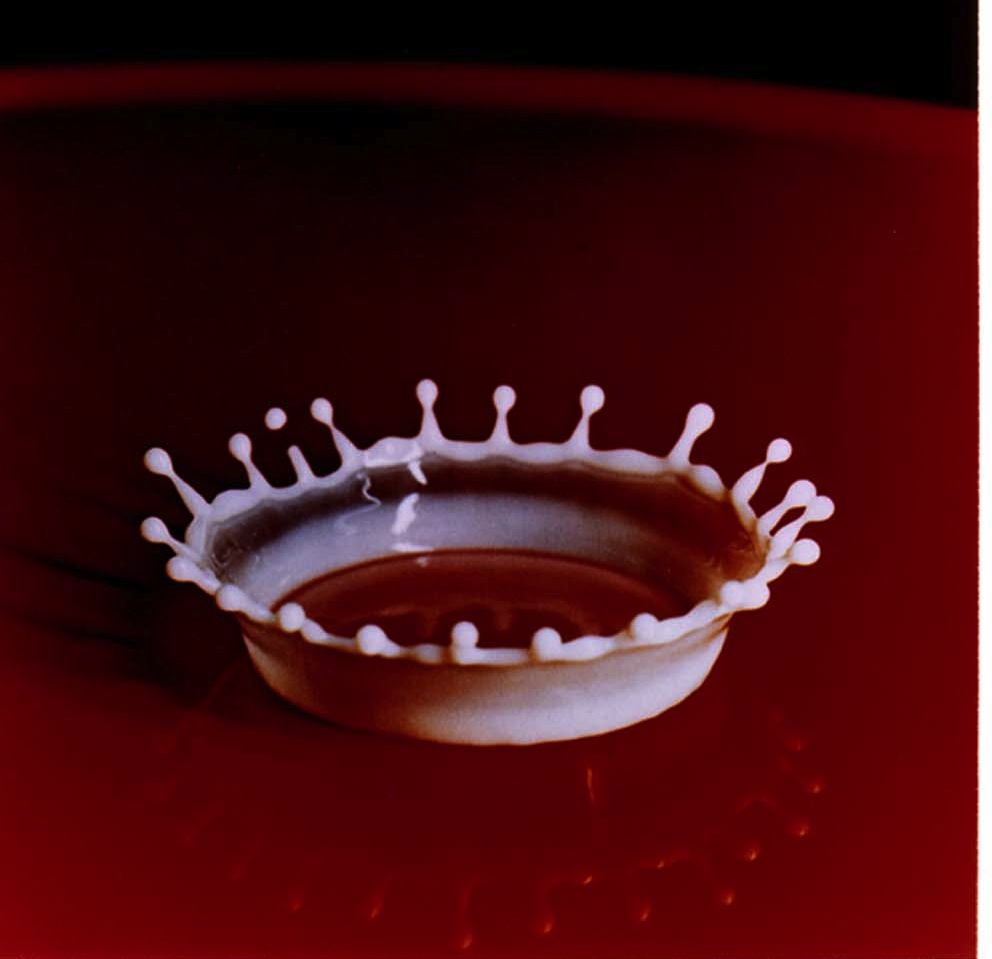

He photographed mundane things, like the milk drop below, in incredibly slow motion or short exposures. He ended up not only with pertinent scientific information, but with thousands of beautiful photographs. They were exhibited everywhere from the Museum of Modern Art to the Smithsonian and published in several books.

- Milk Drop Coronet, Edgerton, 1956. One his favorite subjects, he photographed them repeatedly from 1937 to the 1970s.

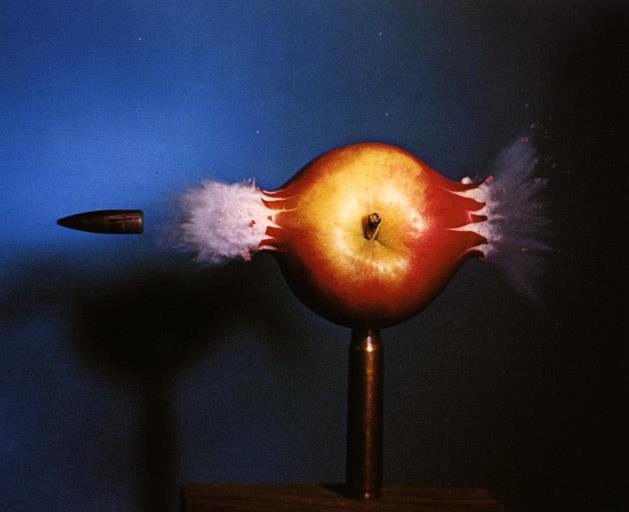

- Bullet and Apple. Edgerton, 1964. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Note that the apple’s stand is a shell casing from the type of round used.

Of course, the camera he developed that could shoot 100 feet of film per minute led to amazing slow-motion video footage. He was shooting video like this in the 1930s, slowing the wing motion of a hummingbird so much that it finally answered the question of how fast a hummingbird’s wings flapped. (Up to 80 times a second — I knew you’d want to know.) Or this one, showing a bubble popping at 2400 frames per second. Or one that demonstrated a cat’s tail is critical to its ability to always land on it’s feet. In 1940, Edgerton won an Oscar for his short documentary, “Quicker’n a Wink.” It’s about 10 minutes long, but worth a view if you have the time.

If he had done nothing but invent the strobe and make amazing stop-action pictures, his place in the history of photography would be secure. And his slow motion videos would have secured his place in cinematography history. But he did a lot more than that.

World War II

“We worked and worked, but didn’t get anywhere. That’s how you know you’re doing research.” Harold Edgerton

Night Reconnaissance

In 1939 America was publicly avoiding involvement in World War II, but quietly preparing for it. Lt. Col. George Goddard, who was in charge of U. S. Aerial Reconnaissance Photography was unhappy with the state of night reconnaissance photography. The state of the art at the time was for a reconnaissance plane to drop a bomb loaded with 500 pounds of flash powder which would be set off in mid-air by a timing fuse. The flash lit the ground and allowed the plane to get photographs.

As we discussed in the last post, flash powder isn’t the most stable substance, plus carrying flash bombs limited the night reconnaissance aircraft to one or two pictures. Goddard visited Edgerton asking if he could help design a better method, which Edgerton readily agreed to. As the meeting ended, Goddard then asked Edgerton to get his strobes and revealed his real motives: Goddard was a photographer and he wanted to go to the circus that night, shooting with Edgerton’s strobe lenses.

The problem, as Edgerton worded it, was like moving from candlelight to sunlight, but during the course of the war he designed and supervised production of 6 different types of in-plane strobe units. These were truly amazing devices with banks of capacitors, self-cooling systems, and multiple tubes and reflectors. The largest of them, the D3, weighed 5,400 pounds, had an output of 43,200 watt-seconds (compare that to a reasonably powered studio strobe with 500 watt-seconds of power). The D3 could illuminate the ground sufficiently to take a photograph from 20,000 feet. (In other words, it could brightly illuminate an object nearly 4 miles (6 kilometers) away.)

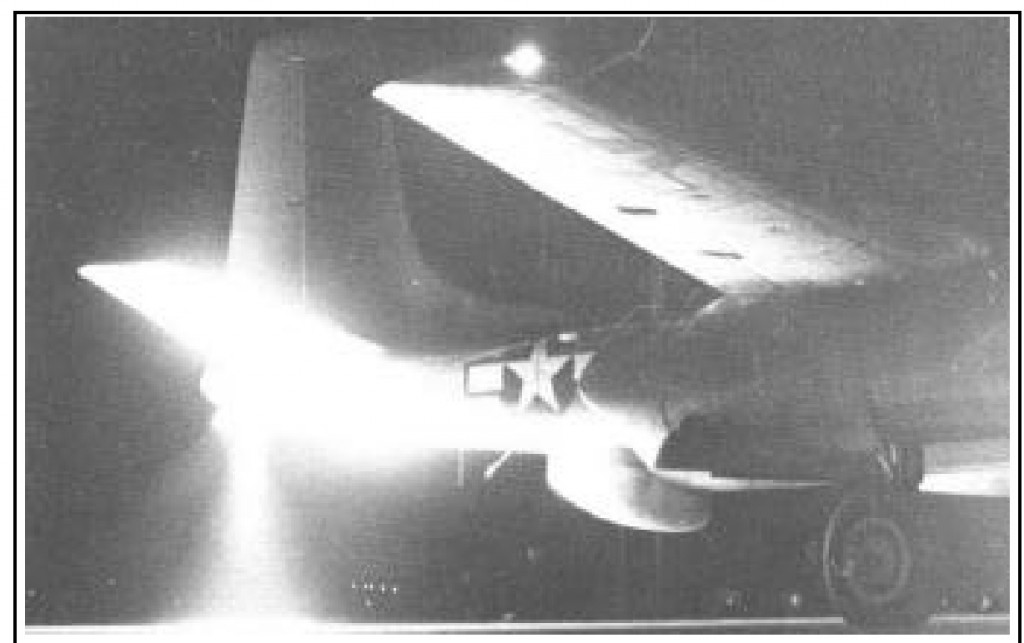

- Strobe light in A-26 photoreconnaissance plane tested before takeoff. These planes used the much less powerful D2 units, which could illuminate to about 5,000 feet.

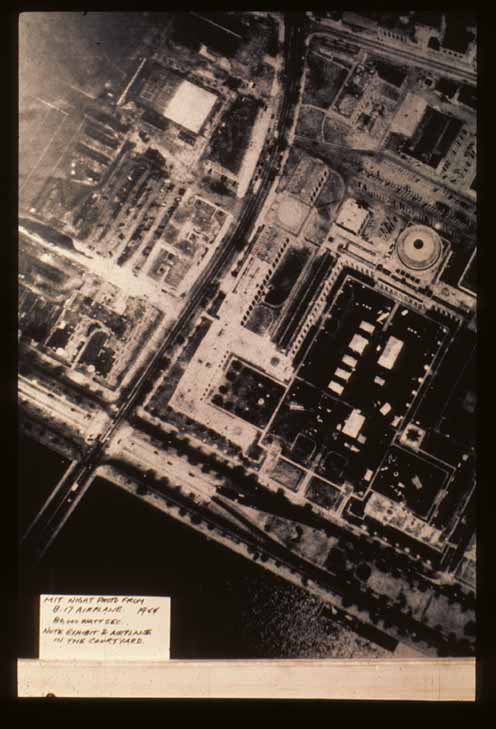

- Night time photograph of MIT taken during testing of aerial strobes. MIT.edu

Edgerton was very hand’s-on during the war, staying at airfields in England and Italy while his equipment was being installed in planes and instructing pilots and airmen in its use. Two anecdotes during this time tell a lot about how he approached problems. When he first came to England, the British Air Force was not at all interested in his techniques, claiming that they couldn’t possibly work. He took a few English officers to Stonehenge in the middle of the night and had an American plane fly over, illuminating the area with a strobe. After seeing the aerial photograph and experiencing the power of the light at ground level, the English were all in.

- Stonehenge, lit by aerial strobes. Ground level image (left) and aerial reconnaissance image (right). MIT.edu

When he arrived at Chalgrove air base, which was very short on space, the base commander was quite irritated and told Edgerton there was absolutely no space for his team to work in. Edgerton and his crew simply went around to the base garbage dump, ‘liberating’ a number of huge wooden crates that airplanes and gliders had been shipped in and other cast-off equipment. Within a couple of days his team was working in comfortably equipped offices with desks, chairs, and filing cabinets – conditions actually much better than the base officers had.

The last line of resistance to Edgerton’s reconnaissance strobes was the pilots themselves. Most of them really didn’t want to fly air recon; they’d rather be fighting and bombing. Some did a purposely bad job during reconnaissance training, hoping to get transferred to other assignments. Edgerton had no trouble overcoming this last obstacle either. He had the coordinates of Britain’s largest nudist colony and would only give out the coordinates for ‘reconnaissance training missions’. He found it provided superb motivation for both pilots and ground crew to obtain the sharpest possible photographs.

Other Wartime Inventions

Developing a night-time aerial photoreconnaissance illumination system would have been a sufficient war contribution for any scientist, but Edgerton was just getting started. The army also wanted his expertise to help them test ballistic systems. Edgerton’s high-speed photographs demonstrated that the recoil of a rifle did not affect accuracy (at least not directly) since the bullet had left the barrel before the recoil raised it. He developed a sound triggering system for his strobes, where microphones picked up the sound of the shell before impact, allowing high-speed photographs that helped the development of armor penetrating shells and shaped charges in bombs.

While working for the Army in England, Edgerton became aware that pilots returning after dark from long missions had trouble finding their airfields because the lighting was inadequate. He spent some time modifying his strobe lights to become landing beacons which pilots could see for miles, even in bad weather. These are the same aerial beacons still used today at every airport and atop any high tower or building today. I’ve no idea how many millions of them are placed around the world, but they started as a Harold Edgerton off-the-cuff idea.

How to Photograph an Atomic Bomb

(This heading shamelessly stolen from Peter Kuran’s superb book title )

While Edgerton wasn’t directly involved in developing the atomic bomb (probably just because he was too busy doing other cool stuff), he was still a part of it. The Los Alamos scientists realized they needed a powerful electronic pulse to detonate the bomb. The only source they could find were the capacitors Edgerton had developed for aerial reconnaissance, so Edgerton was consulted by them.

After World War II ended, the United States embarked on some serious (and to us today seriously crazy) atomic bomb testing.

The 'VIP' section for a Pacific atomic bomb test. Looking quite safe in their goggles.

The Atomic Energy Commission needed very high-speed photographs of things like implosion charges exploding and actual atomic bomb explosions, so naturally they turned to Edgerton.

Edgerton had become famous for short-exposure photographs using a shutterless camera and exposing the film by short, powerful strobe flashes. With these techniques he could routinely shoot at exposure times of 1/50,000 and even 1/100,000 of a second. The good news was an atomic blast wasn’t going to require any outside illumination, so he could leave his strobes and capacitors at home. The bad news was exposure times would need to be on the order of 1/1,000,000 of a second and an actual shutter would be required. This was in an era when a shutter speed of 1/1,500 of a second was considered fast.

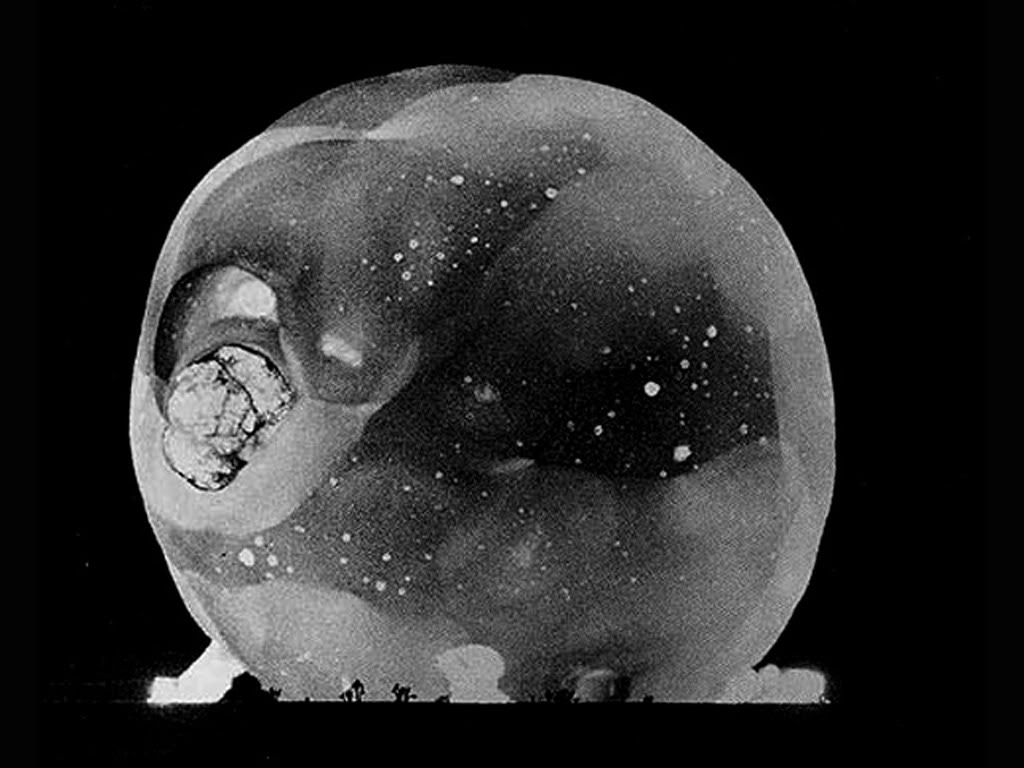

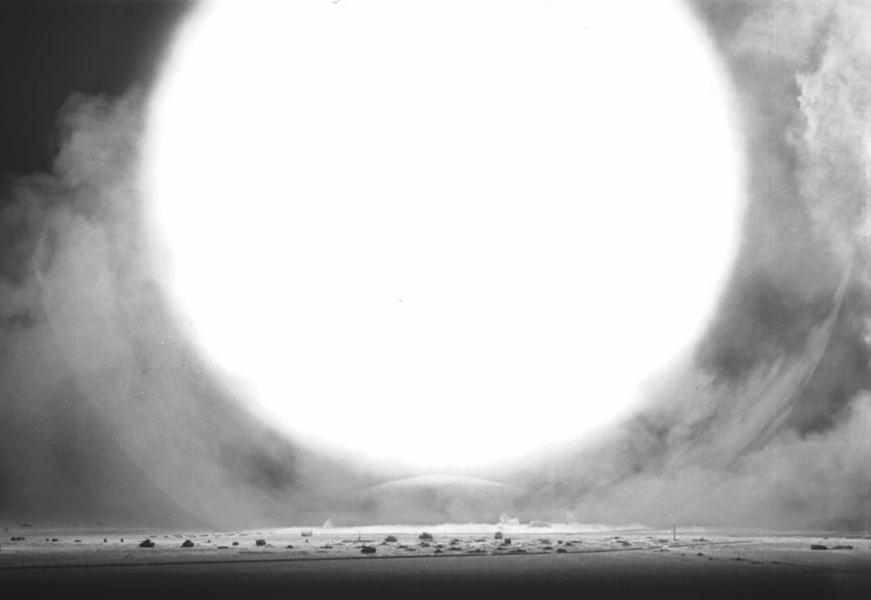

Edgerton took a completely new approach. The Rapatronic Camera he designed used two polarizing filters set at right angles to completely block all light and act as a shutter. An electronic pulse activates a Faraday cell between the two polarizers, changing the polarization and allowing light exposure for the very short duration of the pulse. The Rapatronic Camera could have exposure times as short as 10 billionths of a second, perfect for a little atomic blast photography.

- Nuclear explosion photographed by rapatronic camera less than 1 millisecond after detonation. At this point the explosion is about 20 meters in diameter. From the Tumbler-Snapper test series in Nevada, 1952. Moire artifacts cancelled by Monita and Joe Monk. The ‘legs’ at the bottom are from the explosion travelling along the steel guide wires of the tower.

- Rapatronic image of nuclear explosion. There appears to be some difference of opinion about which test blast this was.

- A bit later in the explosion process, but the exposure is so short you can see the shock waves travelling ahead of the fireball, and underneath the fireball the blast reflecting back from the desert floor.

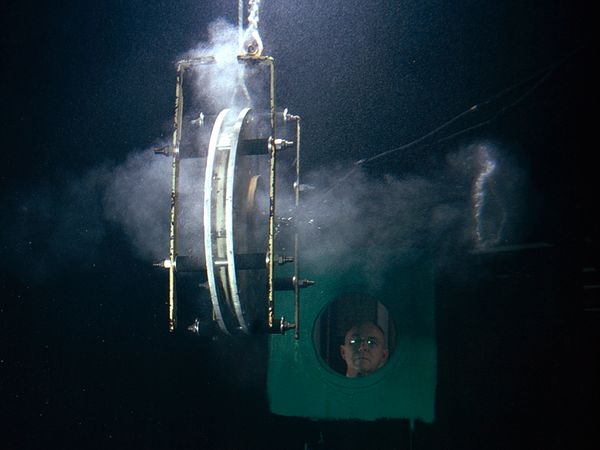

Underwater Photography

In 1952, underwater explorer Jacques Cousteau came to Edgerton, asking his help in improving underwater photography. The two men hit it off and the next summer Edgerton not only furnished equipment to Cousteau, he spent weeks at sea with Cousteau’s crew. He fairly quickly turned the boat’s sonar ‘pinger’ sideways and had it dragged behind the boat, inventing side-scan sonar.

Edgerton and a team of engineers from EG&G perfected commercialized side-scan sonar, which provided accurate, real-time pictures of the ocean floor. From the 1960’s on, virtually every underwater treasure hunter and archeologist invited Edgerton to accompany them on their explorations — and he usually went. These included searches for numerous famous ships and even the Loch Ness monster.

- Harold Edgerton testing a side-scan sonar. National Geographic.

Side-scan sonars are what discovered the remains of the Monitor off of Cap Hatteras, the cabin of the Space Shuttle Challenger in the waters off of Florida, and dozens of undersea wrecks and archeological sites.

And Edgerton saw all that he had made, and it was good.

“Work like hell, tell everyone everything you know, close a deal with a handshake, and have fun.” Harold Edgerton

‘Doc’ Edgerton obviously loved what he did. Every bit of it. In his later years he became an M. I. T. institution and his wing, known as ‘Strobe Alley’ was something of an on-campus tourist attraction. As Kim Vandiver described it:

The other wings of MIT seemed downright sterile. Strobe Alley, the hallway that cut a line between Edgerton’s labs, sucked visitors in and invited them to become part of the action. To make his lair even more inviting Edgerton hung displays all along the hall: photographs, framed bits of equipment, buttons to push. . . . The hallway echoed with the report of gunshots. Flashes jumped across the walls. Boxes spilled wires, capacitors, barnacled wood.

Doc retired in 1968, but apparently no one, including Doc, noticed. He continued to work in Strobe Alley every day, taught classes, and accepted graduate students. He passed away, exactly where he would want to be, I imagine, in the MIT dining hall in 1990.

The legacy he left is almost as amazing as his life. Strobe Alley is now The Edgerton Center at MIT, housing his collections and continuing numerous educational outreach and research projects in high-speed photography. In his hometown of Aurora, Nebraska, the Edgerton Explorit Center provides in-house and outreach educational programs to thousands of people each year. And there are hundreds of his students, assistants, and associates active in research, business, and education today.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

July, 2012

Author’s note: I’ve enjoyed writing this article more than most, largely because of the wonderful material I got to go through in preparing it (if you’re interested in reading more I’ve recommended several books and articles below). In order to keep this article to readable length, though, I’ve had to leave out entire sections of Doc’s life and work, and compress others more than I wanted to. (Really, nothing less than a book could do the man justice.) If I’ve made any errors or misrepresentations in doing so, I would appreciate anyone with first-hand knowledge letting me know, so that I may correct them.

Recommended Reading

Edgerton, Harold: Electronic Flash, Strobe – 3rd Edition. The MIT Press, 1987.

Edgerton, Harold E. and Germeshausen, Kenneth J.: The Mercury ARC as an Actinic Stroboscopic Light Source. The Review Of Scientific Instruments, Volume 3, Number 10, October 1932.

Ghaffar, Roozbeh, et al.: Harold Edgerton in World War II.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flashtube

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flashtube

John D. Anderson, Jr., Modern Compressible Flow: With Historical Perspective, (New York, NY. McGraw Hill, 1990), pp. 92-95.

Kayafus, Guy and Edgerton, Harold: The Anatomy of Movement. BBVA Foundation. 2011.

Kuran, Peter: How to Photograph an Atomic Bomb. VCE, Inc., 2006.

Su, Frederick: Technology of Our Times: People and Innovation in Optics and Optoelectronics. SPIEE Press, 1990.

Vandiver, K. and Kennedy, P.:Harold Eugene Edgerton. A Biographical Memoir. National Academies Press, 2005.

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

John Shriver

-

Ronald Bucchino

-

simon

-

RJ

-

Scott F

-

Arun

-

Robert M

-

Christian

-

David

-

Gordon DeWitte

-

Jon McGuffin

-

John Jovic

-

Samuel H

-

Rahman

-

Bruce

-

Miguel