History of Photography

From the Great Pyramid to Toy Trains: Early Flash Photography

Urochordataphobia

Whenever out-of-print books start arriving at Lensrentals, they know I’m about to write a history article. It happened again last week, and one of the young employees asked me, “why do you write these things?” I told them because I have urochordataphobia — I fear the example of the sea squirt.

A young sea squirt looks like a small fish and swims around all day doing what most sea creatures do (mostly avoiding being eaten by bigger sea creatures). When it gets older, though, one day it sits on a rock and does nothing for a while. Its brain wastes away, it becomes completely immobile, and pretty soon it looks just like a sponge. Now that I’m older, I fear if I ever stop shoveling information at my brain and making it write these things, pretty soon it will find a rock to sit on. And I know where that leads.

Those of you who hate my history articles, please bear with me for a couple of posts. It’s just my urochordataphobia acting up. For those of you who like these history articles, read on and I’ll tell you how flash photography links to toy trains, torpedoes, Alien Astronauts, and common sayings that no one understands anymore.

Early Photographic Lighting

Limelight

Mid-1800s photography, like my own present-day photography, was basically limited to ambient light. Burning a block of calcium oxide in a flame fed by oxygen and hydrogen gases created the brightest artificial light available in those days. The common name for calcium oxide is ‘lime’ (like you spread on you lawn, not like you make delicious pie with) so this type of light, which was used extensively in theaters, was called limelight. No one has used limelight for well over a century, but people still talk about movie stars as being ‘in the limelight’, even though they generally have no idea what a limelight is.

- A limelight. Note the input tubes on the left for oxygen and hydrogen gas lines. Image from Compulite Stagelight History: http://www.compulite.com/stagelight/html/history.html

Limelights were amazingly bright, giving off about 1,000 watts in today’s terms (1). They never really caught on as a photography light source, though. A limelight required a full-time operator to regulate the oxygen and hydrogen gases and rotate the block of lime. Additionally, if calcium oxide gets wet the resultant chemical reaction gets so hot it starts fires. (In fact, it was probably the ‘igniting’ ingredient in Greek Fire.) Having something that starts fires if it gets wet sitting next to tanks of oxygen and hydrogen in wooden buildings probably isn’t the best of ideas.

- Greek Fire www.greece.org

More importantly, limelight doesn’t give off very much blue light, which is what early photographic plates were exposed by. The result, for portraits at least, was the subject was in a light so bright they wanted to close their eyes, while the camera still required a fairly long exposure time.

Magnesium and Flash Powder

Magnesium

Photographers have a long history of fascination with explosive chemicals, so they certainly were aware that a ‘controlled’ explosion could be a good source of bright light. Magnesium was readily available and photographers quickly found that burning strips of magnesium provided a fine photographic light source — very bright and providing a full spectrum of light, including blue light.

It wasn’t perfect, mind you. It was rather difficult to ignite so you needed a fire handy to get things started. Once ignited, however, Magnesium burns so hotly (3,100 °C or 5,610 °F) that it has a tendency to melt whatever it is you’re holding it in and then burn through whatever is under that. (Sometimes this was the photographer.)

Burning magnesium is nearly impossible to stop burning until it’s all burned up. It happily burns not only in oxygen, but also in pure nitrogen, and pure carbon dioxide (which is what they put in fire extinguishers). Magnesium not only burns under water, it actually burns water, creating magnesium oxide and hydrogen. Hydrogen, as the Hindenburg demonstrated, is happy to burn so trying to put out burning magnesium with water actually increases the flame.

Flash Powder

Faced with this list of problems, photographers, being photographers, focused on, “So, how can we make it easier to ignite?” Charles Piazzi Smyth, the Astronomer Royal of Scotland and a skilled photographer, was studying the Great Pyramid of Giza and needed photographs of the dark interior chambers. Having trouble lighting his magnesium flares, he decided that gunpowder, which started burning very easily, mixed with some magnesium powder, just might do the trick.

Surprisingly, it worked pretty well and Smyth’s pictures and thousands of careful measurements of the Pyramid accomplished two things. First, it gave him some temporary credibility as an authority on the Pyramid. Second, it allowed him to demonstrate that while not all scientists are idiots, some certainly are. Smyth was a firm believer in the crackpot theories of John Taylor who believed that the Pyramid was actually constructed by Noah (of Ark fame) and that the British were directly descended from one of the lost tribes of Israel.

Using the thousands of measurements he took (and shamelessly manipulating them) Smyth ‘discovered’ that the British inch was directly related to the ‘Pyramid inch’ and the Hebrew cubit. That meant the inch was a holy measurement decreed by God (and therefore the metric system used by the French demonstrated their godlessness). He was scientifically discredited since many of his measurements were found to be wrong (heck, he was completely convinced the Great Pyramid was the oldest pyramid, which is absolutely not true) and he later changed others to fit his theories. Smyth became the original ‘Pyramidiot‘. His writings were incorporated into a half-dozen religious cults (some of which are going strong today) and later spawned the ‘ancient astronaut’ theories.

Word of Smyth’s gunpowder-magnesium powder spread much more quickly than his Pyramid theories. In the 1800s (or 1700s or 1900s for that matter), the Germans pretty much lived and breathed explosive chemistry, so they probably didn’t take well to this Scotsman inventing this magnesium-gunpowder mixture. Almost immediately, a couple of German-Austrian chemists, Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke, mixed fine magnesium powder with potassium chlorate and antimony sulfide to produce Blitzlicht, the original flash powder.

Blitzlicht changed everything. Well many things. It was available in premeasured packets that could be inserted into igniter trays and ignited easily and predictably. It gave an extremely bright flash that lasted 1/30th of a second. That was a short enough time to make an exposure without the subject blinking (2). Actual explosions with flash powder were much less frequent than with gunpowder-magnesium mixtures, although they still occurred with some regularity (3).

It wasn’t perfect, of course. There was a big cloud of thick smoke left after the flash. There was also the problem of sparks of burning magnesium flying about, starting a fire here and there.

- Modern reuse of a Circa 1909 flash powder lamp. Credit Gentry’s Daguerreian Studio http://www.flickr.com/photos/11964447@N02/3169218441

But the light was good and the cost was low. Photographers were pleased.

In fact, flash powder continued in use long after other forms of lighting were available, largely because it was so inexpensive. It had one other advantage that kept it in use through the 1930s: because flash powder burns just fine underwater, it was the lighting of choice (the only choice, really, flashbulbs tend to be crushed by pressure) for early underwater photographers (3).

- Photograph by Charles Martin & W.H. Longley, National Geographic, 1926.

The Beginning of Toy Trains

Once again I will demonstrate why almost everything worthwhile in the world owes its origins to photography. Soon after there was flash powder, there were flash pans – long trays with a handle that the flash powder was placed in and ignited with a spark.

- The only currently manufactured flashpan. http://www.graflexllc.com/

Joshua Cohen was a college dropout who worked as a battery lamp assembler at the ACME lamp factory. In 1899 he patented a battery-powered igniter that would safely and consistently ignite the flash powder in a pan and a year later patented an improved device. Now flash pans had a battery and switch in the handle and a single photographer could ignite his flash powder with one hand while controlling the camera with the other.

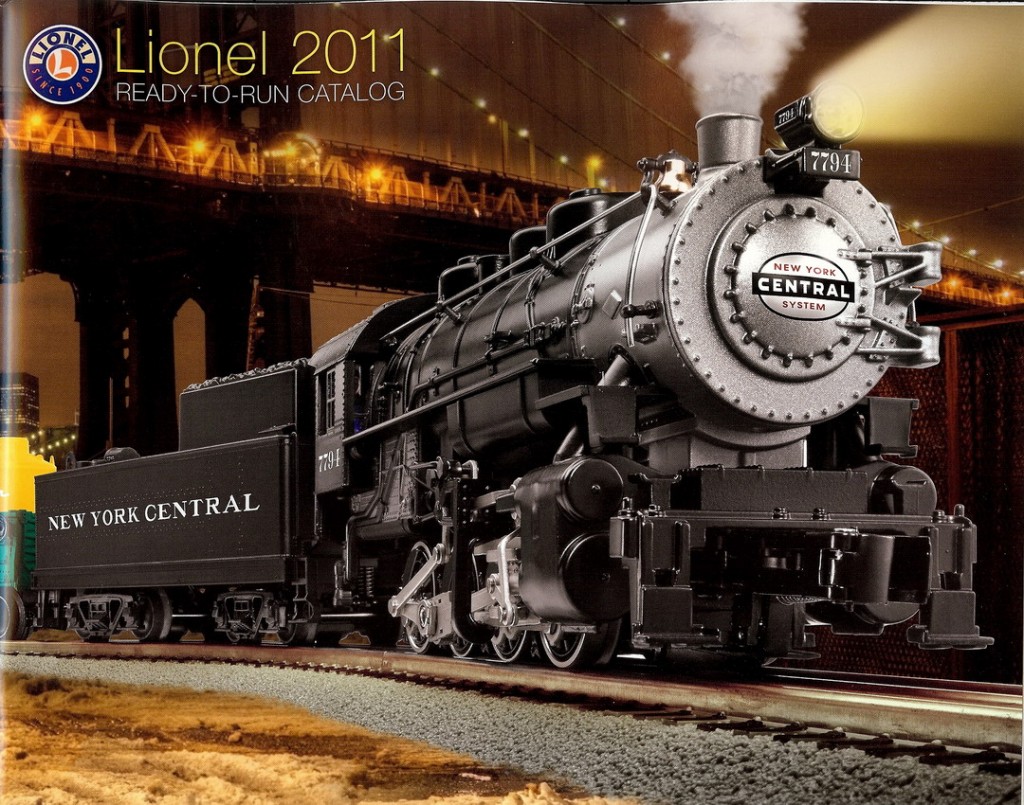

Cohen’s invention was also purchased by the U. S. government, which used it as the igniter for underwater mines and early torpedoes. With the money he received he opened his own manufacturing company that made small electric fans. Cohen was successful, but decided to change his business to one that involved his hobby (I would have liked this guy). I should probably mention Joshua’s full name was Joshua Lionel Cohen and his hobby was model trains. When he started putting electric motors into his model trains, Lionel Trains was born.

There you have it, once again. If it weren’t for photography, none of you guys would ever have opened up a model railroad kit for Christmas.

- Credit: www.olsonhobbies.com

Flashbulbs

The very first flash bulb actually predates the electronic igniter for flash powder. Not much is known of its designer, but a French diver and photographer, Louis Boutan, asked an engineer known only as Monsieur Chauffour to design a flash for underwater use. He enclosed a magnesium ribbon inside a glass jar filled with oxygen and used an electric current to ignite the magnesium.

Paul Vierkotter who placed a magnesium strip inside a glass bulb filled with low-pressure oxygen invented practical flash bulbs in 1925. The lower pressure helped prevent the bulb from shattering during the flash. Once again, a German, Johannes Ostermeyer, perfected the device, substituting thin aluminum foil for magnesium. Aluminum has a very high ignition point, so the flash contained a small chemical primer that was ignited by an electric current.

- Osram Vacublitz. http://www.lampenmuseum.de/

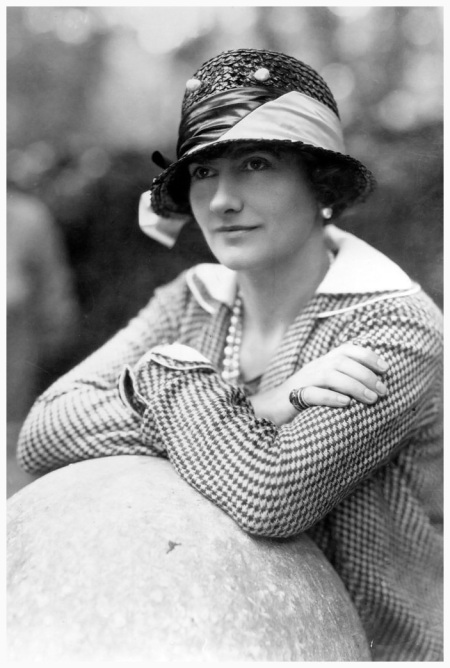

Ostermeyer’s bulb was marketed in Germany as the Vacublitz. Several books (4) state that General Electric Company, Ltd. had the marketing rights in Great Britain and used the name Sashalite as a marketing tool. They consider this the first celebrity endorsement in photography. “Sasha” (Alexander Stewart, a Scotsman who felt the name made him sound Continental) was a well-known celebrity photographer at the time, widely recognized for his careful lighting.

- Coco Chanel, photograph by Sasha, 1929

The reality seems somewhat different. Stewart already had patented some lighting equipment before the flashbulb, and patented modifications after its introduction (5). The London Morning Post announced that Stewart had purchased the rights to the flash bulb and was marketing it himself, and showed photos taken inside a submarine using the new lights in September, 1930. The British Patent Ostermeyer took out was issued in 1930 “as used in the Sashalite” and his corporation, Sashalite, Ltd. may have simply contracted with G. E. to manufacture or perhaps co-market the bulbs.

In any case, things apparently didn’t work out that well for Sasha; he set up a corporation (Sashalite, Ltd.) to handle the flashbulb business and the corporate bylaws stated all profits would be returned to him. When the company’s Board of Directors kept some of the profits as working capital, he sued his own company and lost. Stewart v. Sashalite Ltd (1936) is still used as a reference in Commonwealth courts.

And Then

The development of flash didn’t end here, of course. After World War II flashbulbs rapidly improved, becoming safer, brighter, and faster. The ability to synchronize flash with the camera shutter was developed. (Prior to that you opened your shutter and used the flash to expose, then closed the shutter.) Multiple flash bulb arrays for taking multiple rapid shots were developed. But these were almost all corporate advancements and I’m more interested in writing about the non-corporate personalities.

But while all these corporate flash advances were taking place, a most interesting photographer was investigating lighting (and a lot of other things) from a different direction. I’ll talk about ‘Doc’ in the next post.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

July, 2013

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Gennadi Samoluk

-

David Chorley

-

Aaron M

-

David

-

Brian

-

NancyP

-

Nelson

-

Bernd Schmidt

-

BozillaNZ

-

Don S.

-

Robert L.

-

Zak McKracken

-

L.P.O.

-

Pat M

-

intrnst

-

Mitch

-

Nqina Dlamini

-

Xi

-

Scott

-

Tony

-

Scott

-

Scott

-

Josh

-

KimH

-

Scott