History of Photography

The Space Lens Mystery Screw

We get to do some fun things through our testing company, Olaf Optical Testing. A lot of it I can’t talk about but sometimes we get a project that we can share. One of these came up recently when Matt Leeg asked us if we were interested in testing and cleaning an Angenieux 25mm f/0.95 lens that was probably a backup lens for the NASA Ranger missions sent to the moon in the 1960s. We thought about it for between 0.1 and 0.125 seconds and said, yeah, we could probably do that.

This post won’t help your photography one little bit, nor will it help you with choosing your next lens, or even show you how to fix anything. But for me, it’s a fascinating glimpse into some history from a period I admire — at least from a technology and engineering standpoint. Today we whine about cameras only having 24 megapixels, lenses that only autofocus with 95% accuracy, WiFi access that only allows us to transmit a few hundred kilobits per second.

Suppose I handed you a few TV cameras with low resolution scanning sensors (because there were no CMOS or CCD chips back then) gave you an FM transmitter for bandwidth, and told you I needed high-resolution images of the moon? Today we’d talk about what new technology we needed and how we’re a few years away from being able to do that. Back then, they just said, “OK” and did it.

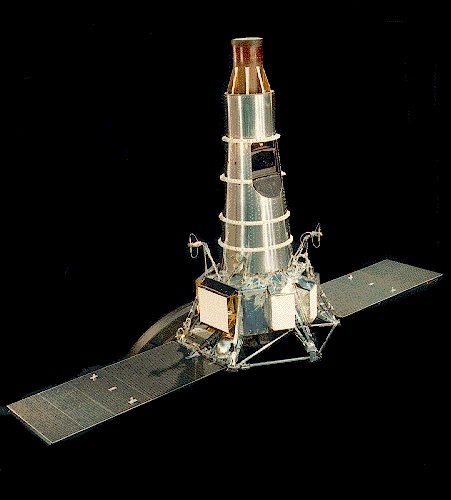

The Ranger missions were from the very early days of space flight, designed to provide high-resolution maps of the lunar surface for the later manned Apollo missions.

- Image courtesy NASA: http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/lunar/ranger.html

There was no way to remotely send the probe to the moon and bring it back. The Ranger probes were designed to crash into the moon, taking pictures right up until the moment of impact.

- The first picture of the Moon by a U.S. spacecraft, Ranger7, 31 July 1964. The large crater on the right is Alphonsus. For scale, Alphonsus is about 108 km wide. Image courtesy NASA: http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/lunar/ranger.html

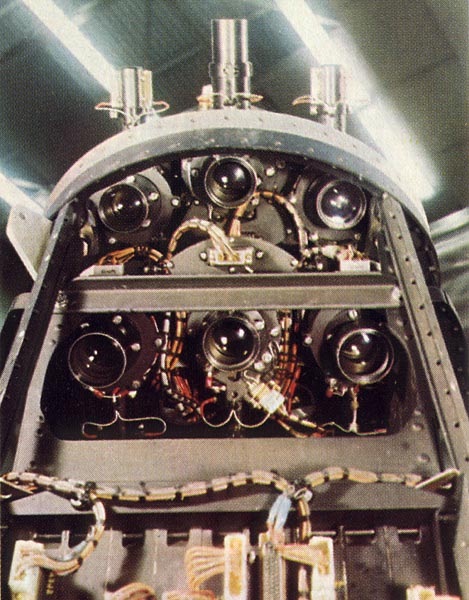

Each Ranger spacecraft had 6 cameras that transmitted on two channels. The F (for full) system had one wide-angle and one narrow-angle camera. The P (for partial) channel had 4 cameras: two wide-angle and 2 narrow-angle. The images provided better resolution than was available from Earth based views by a factor of 1000. All 6 cameras were RCA-Vidicon slow scan TV cameras using C-mount optics. The F cameras recorded 1150 lines over 2.5 seconds, while the P cameras recorded 300 lines in 0.2 seconds.

The wide angle lenses were 25mm (25 degree field of view) and the narrow angle lenses 76mm (8.4 degree field of view). The wide-angle lenses used were Angenieux 25mm f/0.95 M1 lenses with an adapter attached to mount them to the Vidicon cameras. (1)

- Interior of a Ranger probe, showing the 6 camera lenses. The ones on the bottom row are the three Angenieux 25mm lenses (2). Image source: http://www.tvbeurope.com/thales-angenieux-moon-missions-50-years/

Although serial number confirmation of the exact assignment of Matthew’s lens isn’t available at this time, evidence strongly suggests the lens he has (Angenieux Paris 25mm f/0.95 M; Serial Number 1040298) served as a test or backup lens in the Ranger project. How many (if any) of these lenses are still in existence isn’t known. The Angenieux Paris lens was developed in the early 1950s and was extensively used in 16mm cine cameras. They have had a recent resurgence in popularity for use with micro 4/3 cameras on adapters and have become quite difficult to find.

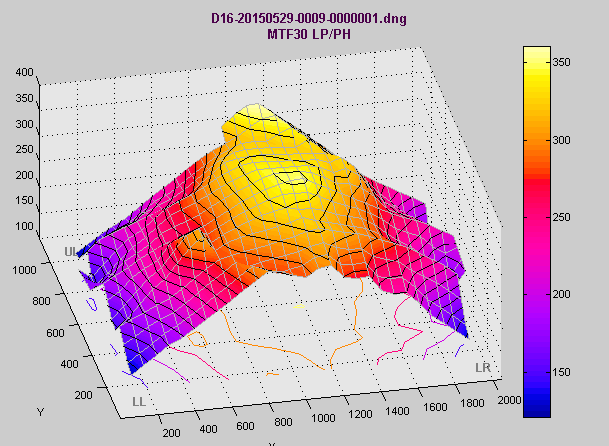

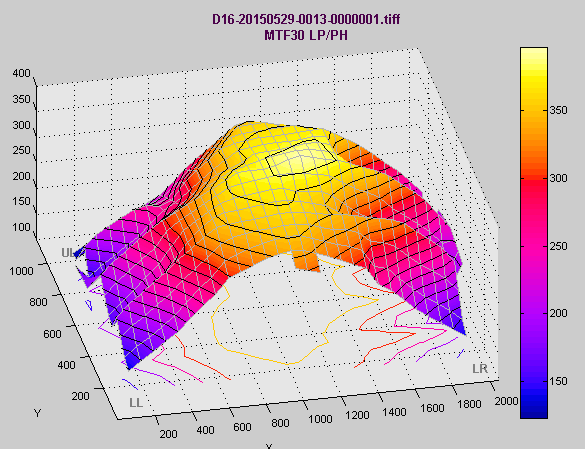

Pre-Disassembly Testing

Before opening the lens we wanted to get baseline testing. We removed the C-mount to RCA camera adapter from the lens and mounted it to a Bolex D16 cinema camera and ran it through the Imatest lab. Why the low resolution Bolex, you ask? Because it’s the only C-mount camera we carry. Because of the camera used, the absolute resolution numbers are going to be low and we couldn’t test at aperture wider than f/1.4, but it gives us a nice look at how well centered the lens is.

- Imatest results at f/1.4

- Imatest results at f/2

There’s really nothing surprising here, other than a 40-year old lens being perfectly centered and not tilted. Still, this isn’t the most sensitive test given what we had to use for a test camera. On the other hand, it was very apparent from the appearance of this lens that it has seen very little use over its 40+ year lifespan.

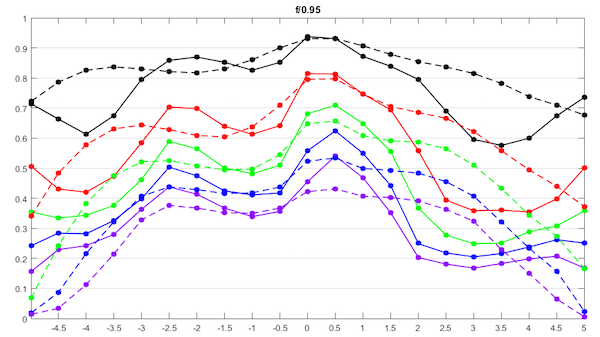

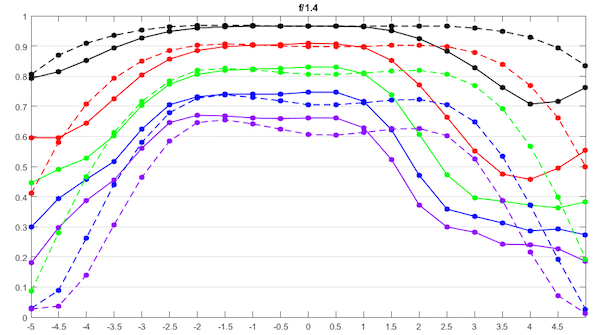

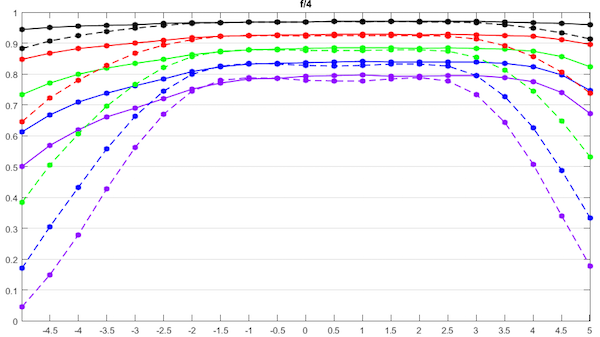

Optical bench testing on the Trioptics Imagemaster bench was more impressive.

- MTF graph legend

MTF curves at f/0.95

- MTF curves at f/2

- MTF curves at f/4

The MTF of the lens is impressive even by modern standards. They are even more impressive when you consider the lens was designed and manufactured in the 1950s.

A Quick Peek Inside

Our goal today isn’t to take this apart and find out every detail. We would like to see if there are any details that help authenticate the lens further and take some photos that might let someone with more knowledge than us about this lens educate us a bit. We wanted to clean a couple of small fibers out of it. We wanted to document it’s internal working condition and check for signs of wear.

But mostly, our guideline was ‘First, do no harm’. This lens is not replaceable. So those of you that think we are all guts and no sense, well, this time we were different. We’d never been inside an Angenieux lens of this era before, so there were a few surprises, though.

The Angenieux, being a C mount lens is quite small compared to SLR lenses of today, smaller than most Leica M mount lens, although of a bit heavier construction.

- The Angenieux 25mm compared to a Leica 24mm f/1.4 Summilux and a Canon 24mm f/1.4

Here are a couple of views of the outside of the lens. The black part at the bottom is the C mount to RCA camera adapter with the screws partly undone.

Unscrewing the adapter reveals the original C mount of the lens.

There was set of three small set screws in the focus ring. We originally thought removing these would allow us to remove the focusing ring. Not so much. It just allowed us to screw up the back focusing distance. But (not luckily, from long, unfortunate experience) we had carefully measured the back focus distance on the optical bench so we knew we could reset this without difficulty.

Since the back of the lens didn’t want to cooperate, we moved to the front where there was an obvious spanner ring, with some obvious spanner wrench holes just begging to be removed.

Once the ring was loosened a bit, simple friction with a rubber stopper was enough to finish removing it.

The spanner ring came out easily.

But instead of the front element coming out next, we found there was a second spanner ring under the first one that also had to be removed.

That’s the kind of over engineering that you just don’t see these days. One thing we considered was if the second ring was added to prevent any vibration loosening for use on a space probe, but it really seems to be a standard part of the lens. But that’s just an educated guess, as we’ve never seen an Angenieux 25mm M f/0.95 before. If any of you have one, we’d love to know if yours has the same arrangement up front. At any rate, the second ring was just as easy to remove as the first.

With the two spanner rings removed, the front group came right out.

This let us clean out the 2 tiny fibers we could see in the front of the lens. It also was where we decided we’d gone far enough into the lens from this direction. We could have removed the second group but could see no reason to do so – we could inspect the rest of the front barrel without removing the second group.

Turning our attention to the back of the lens, we noticed that the black inner barrel and rear outer barrel rotated in opposite directions, adjusting the back focus with the setscrews removed. Between these two barrels was a thick grease.

We were a little surprised at this since most lubricants are removed from lenses going into vacuum. However, certain heavy lubricants, and this certainly appears to be a heavy lubricant, are vacuum proof. Looking at this lubricant at 10X magnification, it’s as thick as anything we’ve seen, though. If any of you reading this are more familiar with these lenses than we are, we’d appreciate any input.

Lubricant on the tip of a toothpick, magnified 10X.

After getting the grease sample, we unscrewed the rear barrel from the lens.

Which exposed the rear internal section of the lens.

There were spanner notches in the focus ring retaining plate, which came off easily.

Removing the retaining ring and spring washer . . . .

Let us take of the focusing ring.

And here our disassembly came to a halt. There is a screw under the focusing ring that should be removed next to separate the front and rear barrels (red arrow). It was immediately apparent that this screw had been modified in a very odd way, preventing us from removing it simply.

It’s a slot-drive screw and one side of the screw had been shaved down so the slot no longer existed, as you can see in the close-up below. We thought, at first, that we might still be able to remove the screw, but we quickly found we couldn’t remove it without damaging it – probably we would have to drill the screw out and we weren’t about to do something like that to this lens.

Obviously we don’t know exactly how or why the screw got this way. Our first thought was it had been damaged during a previous disassembly. (We knew we were not the first ones to open this lens; there were small signs that someone had done that before. But we would have expected that if NASA used the lens.) But a slot screw that is damaged during removal or reassembly is damaged in opposite quarters, not along one side like this. It could be possible that some form of wear or tear affected the screw, but it’s recessed and there is nothing that could appear to rub across it during lens use. Not to mention, metal fragments that big would have been obvious to us – and from this location there’s no way they could fall out of the lens.

Our best guess is that after the screw was inserted, someone filed or shaved off one side so that the lens could not be disassembled again. I have no idea why that would be done by NASA. It may have been protocol during assembly by Angenieux if there were optical adjustments made during assembly, after which they didn’t want anyone opening the lens. At any rate, I have a tiny bit of hope that someone reading this will be knowledgeable about these lenses and will tell us what went on here.

In the meantime, we have reassembled the lens, repeated all of the testing to adjust back focus and make sure the optics remained excellent, and sent it on it’s way back to Matt. And yes, the guys doing the disassembly and reassembly all breathed a huge sigh of relief when we knew it was back in perfect (and a bit cleaner) order.

The team: Brandon "Brains" Dube (left), Aaron "Hands" Closz (center), and Roger "Fine-ass Shoes" Cicala (right)

So what did we learn today? Nothing, really. We created more questions than we answered. But perhaps someone out there can help us with the mystery of the unremovable screw, and the question of the remaining lubricant. But we did get to hold a bit of remarkable history in our hands and take some pictures of it. It was a bit humbling for me to think about what those engineers accomplished with pretty primitive analogue equipment back in the 1960s.

Given the recent popularity of Angenieux 25mm f/0.95 lenses among micro 4/3 cinematographers, I wouldn’t be surprised if this is the only remaining lens from the Ranger program (other than scattered pieces on the moon). We don’t know how many there were originally and they apparently were sold off years ago. Since Angenieux 25mm f/0.95 are hard to find and fetch a premium price, chances are high that the purchasers just removed and threw away that weird mount on the back without a second thought.

Roger Cicala, Aaron Closz, and Brandon Dube

Lensrentals.com

June, 2015

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Kadir Kirisci

-

obican

-

mgeee

-

Markus Keinath

-

Heins

-

Jack

-

Larry Bauer

-

MarkB

-

Tony Oaten

-

Will Humber

-

Barus

-

Frédéric

-

Nqina Dlamini

-

Kevin Macke

-

Jeff Cowan

-

Mike Griffin

-

John Leslie

-

Asad

-

Joachim (Switzerland)