Roger's Corner

Fun with Color Vision

I’ve been doing a lot of technical things lately, writing up our repair data and investigating methods of reducing optical variation in lenses. So I thought I’d take a bit of a break and write a post about something fun. Human vision is always fun to me, since it’s an area where I can apply both my photography and medical experience.

Most of you probably know some of these things, but I bet most of you don’t know all of them. So I would recommend skimming along this rather long post to find the topics that interest you. Since it covers (among other things) carrots, advertising, Impressionist painting, evolution, optical illusions, and warship camouflage, there ought to be something of interest somewhere.

Carrots

Did your mother ever tell you to eat your carrots because it would improve your eyesight? You know that isn’t true, right? But did you know that this urban myth began as a government-sponsored disinformation program? Don’t get all politically hackled, it was back in the 1940’s. Great Britain had deployed radar-guided night fighters and knew Germany would notice a sudden increase in the number of planes shot down.

Great Britain decided to take care of two things at once: They needed to keep the Germans from finding out how good their radar system was and they were rationing almost every food imaginable and trying to get people to plant vegetable gardens. So they released a story that their leading night-fighter ace, John Cunningham, was nicknamed ‘Cat’s Eyes’ because of his amazing night vision that let him see German planes in the dark. Then they followed up by saying they’d discovered his night vision was so good because he ate massive quantities of carrots and they had started feeding carrots to all of their pilots with amazing results.

This not only fooled the Germans, it got British citizens planting carrots in their backyards so they could see at night during the blackouts. It also caused my mother to force feed me carrots as a child and I hate them to this very day.

As an aside, did you know that carrots come in lots of colors besides orange? Actually, the original carrots were purple. Dutch breeders in the 1700s created the orange carrots we’re all used to. Makes you feel rather inadequate about that little team flag in your front yard, doesn’t it? When the Dutch want to display their team colors they create a whole new vegetable.

- Carrot colors. Original images http://www.carrotmuseum.co.uk/

What has this to do with photography you ask? Well it provides a superb segue to talk about color vision, that’s what. OK, maybe not superb, but it’s decent. And I’ve been trying to work that carrot story into a blog post for months.

Color and Monochrome Vision

Pity Us Mammals

Most of the so-called ‘lower animals’ like birds, reptiles, insects, and fish have four types of cones cells and can distinguish far more colors than we can. There is some evidence that pigeons (AKA flying rats) actually have five types of color sensing cone cells, making them the color vision champion of the animal kingdom. They can even see into the ultraviolet spectrum. This probably explains why your pet pigeon isn’t too interested in your brightly colored photographs; he would find them dull and lifeless. (On the other hand, we humans don’t fly full speed into mirrored buildings, so I guess there’s always a trade-off.)

- Wavelength sensitivity of the 4 cone receptors in bird eyes. Wikipedia Commons

Almost all mammals either see in monochrome or dichrome. Dichrome mammals have two types of cones and can distinguish blue, green, and yellow—but not reds or oranges. Only primates and a few other mammals see three colors like we humans do.

So what happened to us? Early mammals were largely nocturnal and depended on scent and sound to find their meals (and to avoid becoming one). They didn’t need color vision, so they lost it – at least down to two types of color-sensing cone cells. Primates and a few other mammals (mostly tree living) gained a third, red-sensing cone, possibly because red and orange are the colors of many fruits that they eat.

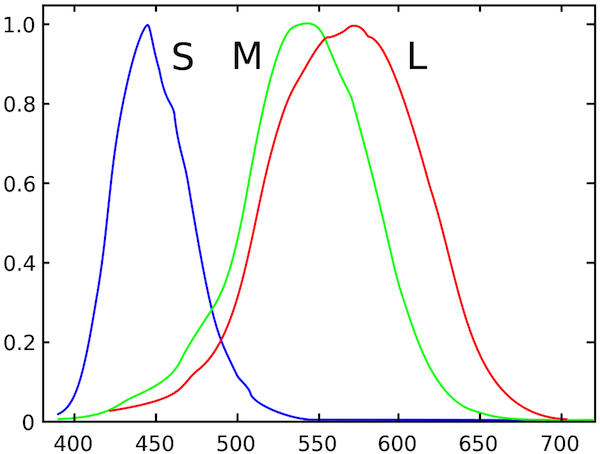

But the red cones we mammals have are actually mutated green cones (and the reason some of us are red-green colorblind is that we didn’t get the proper mutated gene). The graph below shows how the ‘red’ human cone is just a bit different from the ‘green’ cone, not spread out through the spectrum as nicely as the bird’s cones above. Our brains have to do a lot of processing with the information it receives for us to perceive color properly. All of this processing makes for some interesting side-effects and a lot of interesting art.

- Sensitivity of Human Cone Cells. from Stockman, MacLeod & Johnson (1993) Journal of the Optical Society of America A, 10, 2491-252, modified by Vanessa Zekowitz

What Color is Grayscale?

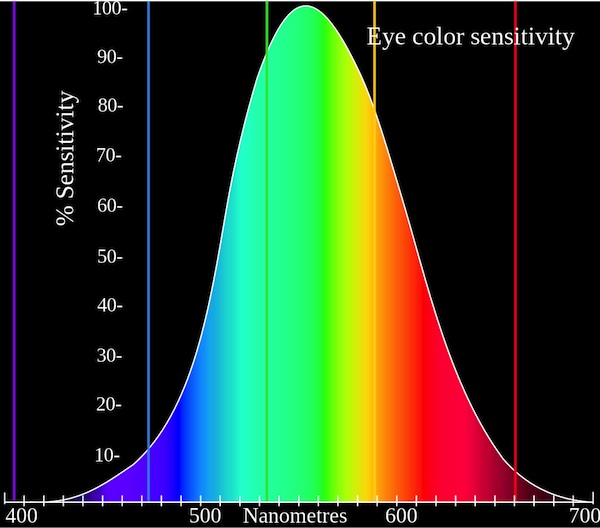

In nice bright daylight, my cone cells are sensing all the colorful objects around me. Each type of cell is most sensitive, as you can see from the graph above, to certain wavelengths of light. If we sum all of this sensitivity together we’d find we’re most sensitive to greenish light, and least sensitive to red and blue. That’s nice – but you already knew that.

- Graph: Adam R?dzikowski, Wikipedia Commons

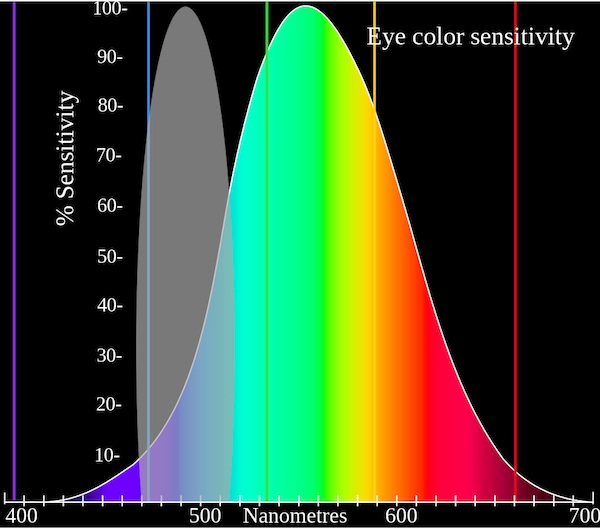

But what if I look at that same colorful scenery on a dim evening. All of the same wavelengths of light are still hitting my eye, but at much lower luminance. Now only the rod cells (what we think of as the black-and-white sensing cells) in my eye are working. Logic would suggest they should also be most sensitive to green light, but they aren’t. They’re more sensitive down in the blue area.

- The Rod cells (gray area) are more sensitive to blue light.

Does it make a difference? Actually it does, a little bit. For example if you put some red apples in a blue bowl, the fruit will look brighter than the bowl in daylight. In dim light, after your eyes have acclimated, the bowl will look brighter than the fruit. Yeah, I know this is pretty useless, but now when your wife asks if you’re reading that stupid photography blog again you can say “No! I’m doing science!” and threaten to show her what you’ve learned.

This principle can help a bit when we convert color images to black and white. Below are an image of a carousel in color, after a standard black-and-white conversion, and converted to black-and-white with green emphasized (like daylight vision) and blue emphasized (like night vision). They are slightly different.

Look at the stripes on the pole in the foreground or the trim on the ticket-taker’s booth. Default black-and-white conversion can lose some details that our actual vision would never lose. Playing around with Channel Mixer for your black-and-white conversions, starting with a green or blue emphasis, will often be more realistic than the standard ‘convert-to-grayscale’ conversion.

Vision Processing and Why I Like to Work in LAB

I promise not to go all neurophysiologist on you (those guys are geekier even then me, and can spend hours arguing over things like opponens-processing theory and close-area inhibition). But there are some interesting things about vision processing we can discuss without going there.

Visual information leaves the eye along the optic nerve and travels to the middle of the brain (the thalamus) for preliminary image processing and then to the back of the brain for more intensive processing. The anatomy and stuff aren’t particularly important for my purposes, so we’ll just skip over the 30,000 words it would take to describe them all. I will mention that “blob cells” and “interblob cells” are involved, just because I found those names awesome compared to Latin terms like Lateral Geniculate Nucleus, koniocellular neurons, and extrastriate cortex. Those latter terms can be useful, though. If you want to share the carrot story, for example, you’ll sound a lot smarter if you say something like, “I was reading about vision processing in the Lateral Geniculate Nucleus and koniocellular neurons yesterday, and discovered that carrots aren’t really good for your eyes.”

Anyway, the bottom line (well, one of the bottom lines) is the brain separates out visual information into two different major streams.

- The first stream (called the dorsal or ‘where’ stream) processes images in monochrome. It detects luminance and high resolution, has binocular vision with depth perception, locates objects in 3 dimensions and tells us how they are moving (or not moving).

- The second stream (called the ventral, or ‘what’ stream) processes the color and shape of objects (it’s very sensitive to edges) and connects with other centers of the brain that identify objects. The ‘what’ stream is actually of much lower resolution than the ‘where’ stream.

People who suffer damage to these areas of their brain have very strange problems. When the ‘where’ system is damaged, for example, the person may find it impossible to cross a street — they can see a car coming but have no idea how far away it is or how fast it is travelling. When the ‘what’ system is damaged people may no longer see colors or may not recognize objects. They might describe the parts of a person’s face (blue eyes, thick eyebrows, large nose) but not be able to recognize that person is their brother. (If you find this kind of thing interesting, I highly recommend “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, and Other Tales” by Oliver Sacks.)

What does this have to do with why I like to work in the LAB colorspace (as opposed to the standard RGB) when I’m playing in Photoshop? One reason is because LAB separates an image much like the brain does, into a high resolution monochrome image (the Luminance channel of LAB) and two lower-resolution color channels (the A and B channels of LAB).

For those of you who aren’t familiar with it, let me show you a quick example. The image below shows a flower, with the Luminance channel and combined A and B channels separated out below it.

- Normal image (top); combined AB color channels (bottom left) and Luminance channel (bottom right)

If you haven’t worked in LAB before, or haven’t studied color theory in art school, you might be shocked at how little information the two color channels seem to contain compared to the luminance channel. Now you understand why some video codecs (and jpg for that matter) can compress the hell out of the color information without affecting the image all that much. You also understand why those rare neurologic conditions that cause loss of luminance perception but retained color perception, leave their victims nearly blind. (Human vision isn’t quite like this; our color vision emphasizes edges, but it’s similar.)

Just in case you think that color information isn’t important in everyday life, though, try to identify 10 of the fruits in this black-and-white image.

Yeah, you were pretty lost after pineapple, weren’t you? Adding that low resolution color makes an impressive difference, doesn’t it? It also is a good example of why primates, who loves them some fruit, had an advantage with color vision over the monochrome mammals.

Fun in LAB

While the LAB color space in Photoshop isn’t necessarily better than the the RGB most people work in, it lets you do some things you could never do in RGB because you can basically manipulate the heck out of the color channels. For example, if I invert the flower photo from above in RGB I get the image on the right, while if I invert the color channels in LAB I get the image on the left. Pretty different.

Or I could just invert the B channel and get this. Just the ticket if I want to make everything look like a scene from “Avatar”.

Or if you like oversaturated colors, you can do it to a huge degree in LAB because you can manipulate the heck out of those color channels without adding noise or blowing out highlights or shadows. Accomplishing the same thing in RGB would cause all kinds of artifacts in your image.

Why would you want to do any of this? I don’t know. But there are things that can be done much more easily in LAB. Restoring unrecoverable blown highlights, sharpening images that have chroma noise (or reducing chroma noise), artificially coloring images, and a number of other things are easy as pie in LAB. Of course, there are other things that are easier in RGB. I think.

Fun with Luminance and Color

Those of you with fine art degrees already know most of this section, but those of us who aren’t so trained may find it interesting.

(Note: all of the images below depend on your computer’s monitor settings and your own visual perception. You may not see the effects I describe.)

Equiluminant Colors

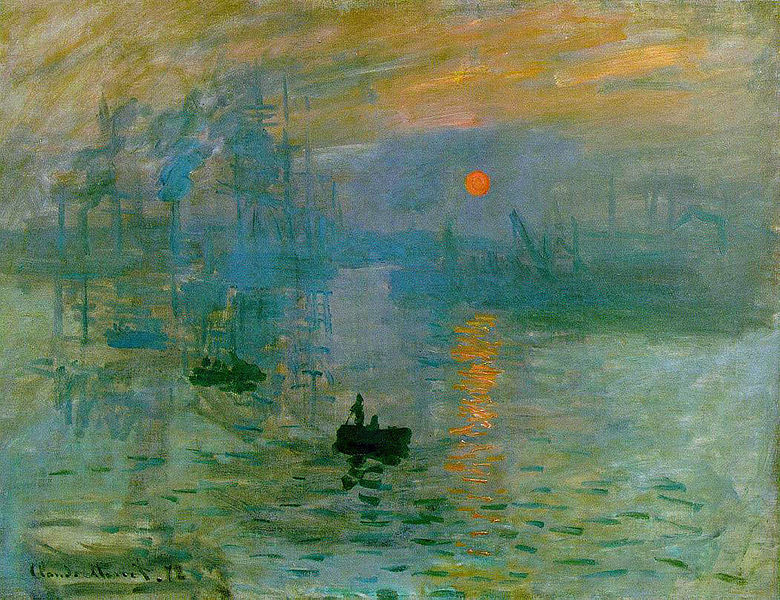

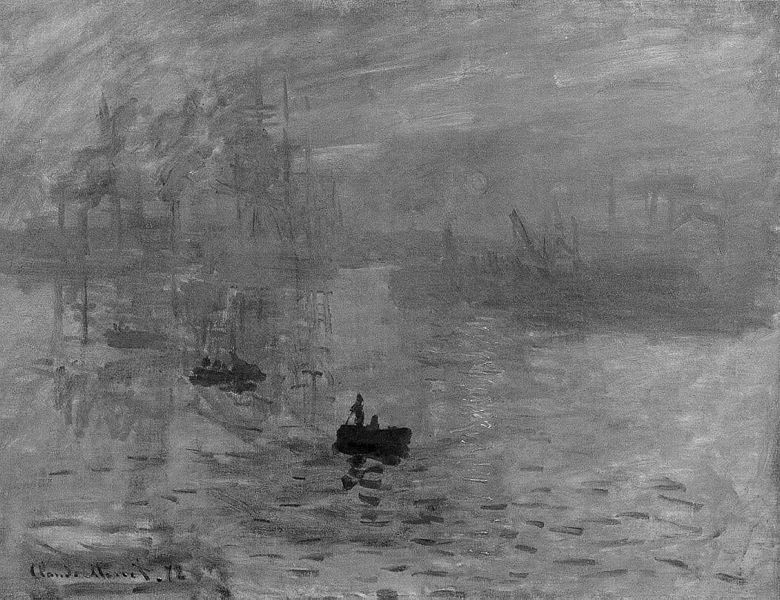

Painters have taken advantage of the fact that the position and motion sensing parts of vision processing work on the luminance of the image, while object recognition depends more on color and shape, for a long time. A classic example is Monet’s “Impression, Sunrise“.

- Impressioin, Sunrise Claude Monet, 1872

The sun is very dramatic. A lot of people, if they look at the picture for a while, see the sun seem to twinkle or vibrate a bit. If you look at the luminance of the image you can see why: the sun is nearly equiluminant with the sky around it. The position sensing part of the brain doesn’t have good data to say exactly where the sun is, but the object sensing part of the brain sees it very clearly.

- Impression, Sunrise, luminance

A lot of impressionist artists used this technique, although Monet was the master at it. His “Wild Poppies Near Argenteuil” does exactly the same thing with the poppies in the image, making them seem to almost move in a breeze. (I’ll let you do the grayscale on this one.)

One other nice technique here is that the bright red flowers in the foreground aren’t quite equiluminant so they grab the eye, while the background, equiluminant flowers emphasize the sensation of distance.

"Wild Poppies Near Arenteuil", Monet, 1873

I know most of you don’t plan on painting anytime soon, but you can use this technique to modify a photograph of sunsets, flowers, or other colorful objects, using a ‘lighten’ or ‘darken’ brush to move the Luminance more towards neutral, and perhaps boosting the color channels a bit. A hint, though: only work in areas of mid-luminance. You’ll get color artifacts if you do it in areas of shadow or highlight.

Equiluminance for Fun and Profit

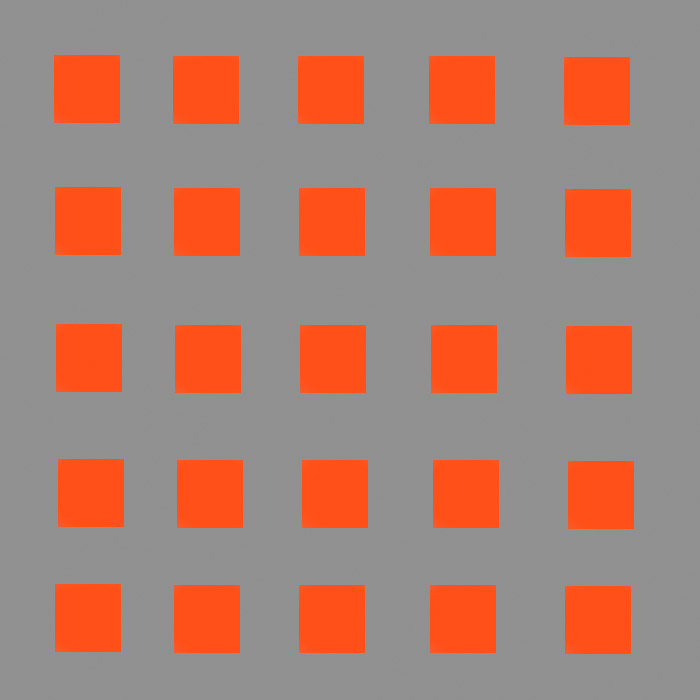

Equiluminance is one of the simple techniques used in optical illusions. The boxes below, for example, are color only, the luminance of both the orange squares and the gray background is 50%. The orange squares are square, but depending upon exactly how your brain processes things, they may have a halo or edges around them, may appear tilted, or jittery.

The image is just hard to look at (try looking at the second square in the second row and moving to the 4th square in the fifth row). Eye movement is controlled by the part of the brain that senses luminance and with no luminance to grab on to, it has trouble controlling where to send your eyes as you look around the square.

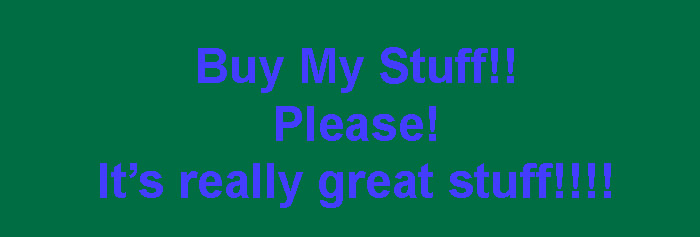

Now why on earth would anyone want to make something that’s so difficult to look at? One reason is because they want to sell you stuff. In the example below, the text is equiluminant and therefore quite difficult to read. So guess what we curious humans do when confronted by difficult to read text? We read it slowly. One. Word. At. A. Time. And that makes us more likely to retain the message. If it is a screaming, black-and-white headline our brains would immediately recognize it and discount it.

Generally an advertiser isn’t this blatant. They’d put the equiluminant text in with some graphic art, or perhaps even as part of a photograph. Or they use other tricks like different colored or different sized letters, putting the text on curved lines. But advertisers know if we don’t immediately recognize text we’ll spend a few seconds figuring out what it says. Every time.

Luminance Shading and 3-D

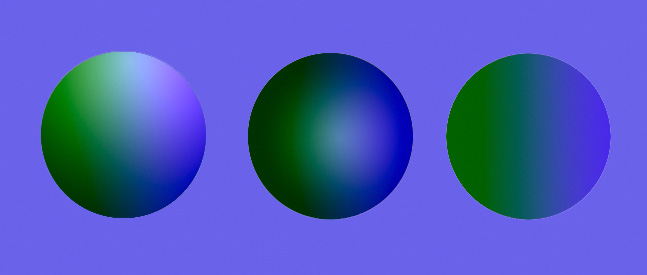

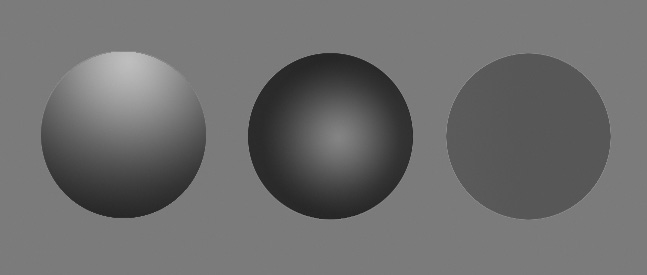

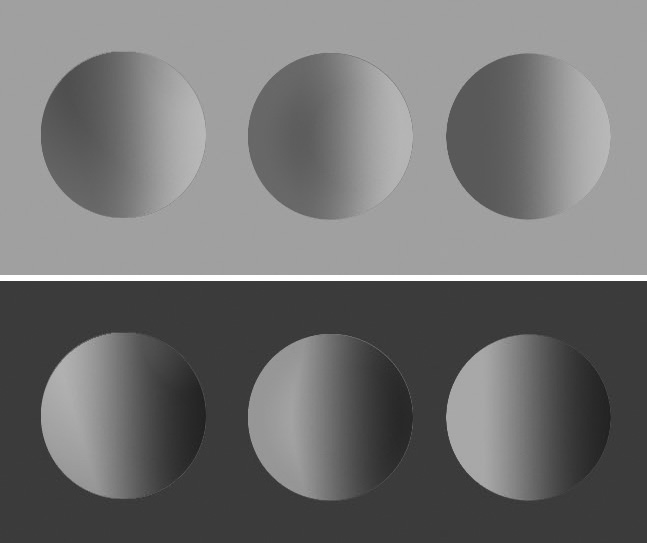

I mentioned earlier that the ‘Where’ system that is responsible for locating objects in space is monochromatic and luminance dependent, while the ‘What’ system that helps recognize objects recognizes colors and edges. If you look at the circles below, two have a bit of 3-D effect while the one on the right appears perfectly flat.

You probably won’t be a bit surprised to find that luminance has a lot to do with the 3-D effect, with the two balls on the left having luminance changes, while the one on the right has none, as shown in their Luminance channel below.

- The Luminance channels for the image above.

If I show you the two color channels, you’ll see the three balls are identical as far as color goes. (In fact, the way I made the drawing was to draw a ball using a blue-green color gradient, copy it three times, make black-white gradients in just the Luminance channel.)

- The A and B channels for the balls in the illustration above. All 3 balls have identical color.

The take away message is you can’t give objects a 3-D look with color, it’s entirely a luminance thing. (Shading a color from light to dark is entirely a luminance thing, too. The color doesn’t change, simply the amount of luminance of the color.) There are many other factors, such as perspective, shading, and haze that go into depth perception, but this aspect of an object’s 3-D shape is basically luminance.

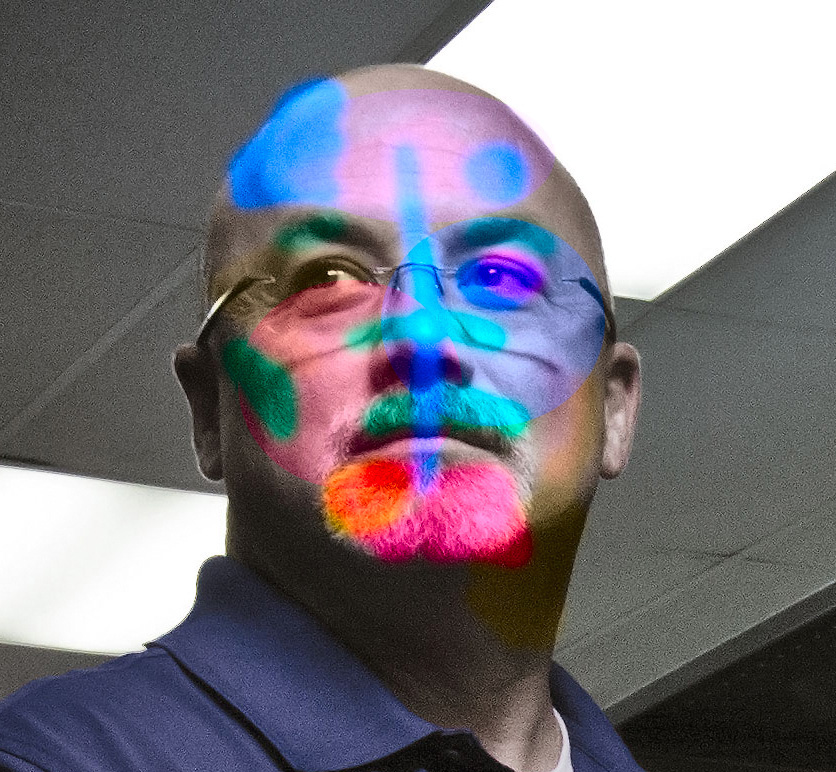

For the same reason, a bizarrely colored face with unchanged luminance, is simply a bizarrely colored face. We have no trouble recognizing what it is or even who it is.

If you paint something with huge differences in luminance, though, it becomes difficult to recognize. That’s the main concept of “dazzle camouflage” used on ships since World War II (and as recently as 2013 on the USS Freedom). Dazzle doesn’t particularly hide the ship (or other object), it makes it difficult to tell what the object is, and how it is moving.

- USS Charles S. Sperry in “Dazzle” camouflage paint

There’s a million other fun things that separating color and luminance do to our vision. And there’s a lot more than just color and luminance to visual processing. But this little bit, hopefully, provided a ‘fun fact’ or two you didn’t already know.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

August, 2013

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Ron Miller

-

Finn K

-

MikaA

-

Andrew

-

Doug Gorsline

-

alek

-

NancyP

-

NancyP

-

Tim

-

Fritz

-

Ruy

-

Fritz

-

Richard S

-

andres w

-

Samuel H

-

Burton Randol

-

Pat M