Equipment

Why We’re Going to Start Testing Cinema Lenses. And Why We Haven’t Before.

Here we go again. This isn’t my first time pissing off the status quo; I’ve been doing it for years. We spent the last few years developing better metrology (lens testing) for photography lenses. The reason was relatively simple; photography cameras with higher resolutions began to see flaws that the photography company’s (and our existing) metrology couldn’t see. Test charts and lens test projectors just didn’t cut it anymore.

We don’t keep our methods secret. We write some up on this blog and publish others in peer-reviewed journals. Of course, the industry isn’t always enthusiastic about it. Their existing methods said their lenses were fine, and change is expensive. But as more and more users complained about defects they could see in their images that the manufacturers couldn’t see in their testing we had engineers from most of the major manufacturers visit to see what we’re doing. Over the last few years, most have started improving their metrology. A few are enthusiastic about it, most a bit grudging, and some just repeat ‘it isn’t necessary’ over and over.

During this time we’ve tested many thousands of photo lenses and maybe a dozen video lenses. Why? Well, because there was no reason to MTF test video lenses. So why start now? Because pretty soon there will be a reason to. So before I start rolling out MTF charts of video lenses I thought I’d put up a bit of a post about our ‘why now.’

Why We Haven’t Bothered

Lenses for video and cinematography are different than photo lenses in some distinct ways, but many of you will be surprised at some of the ways they aren’t different.

Cinematographers are very concerned about the ‘look’ of a lens, its color rendering, focusing accuracy, lack of focus breathing, parfocal zooming, how it handles flare and a dozen other things. They are interested in having a ‘sharp’ lens, but sharp is a vague term and very different in video and photo work.

Video is shot on much lower resolutions sensors than a photo, and there is less concern about the highest resolution. Photographers, with their higher resolution cameras, worry as much about absolute resolution as they do about contrast. In testing, fine resolution is referred to as high frequency. Test charts or lens projectors are perfectly great at low-frequency testing. There’s no need to use fancy optical machines for that.

Why We Are Bothering Now

The key here is that if you shoot on a high-resolution sensor (assuming a good lens), you see fine detail that was invisible before. Two very close points look like one point at low resolution but become two points in the image as the resolution increases.

If you quadruple the number of pixels on a sensor, you theoretically double the resolution of your image; you can see the detail that wasn’t in the low-resolution image. (This assumes you have a good lens in front of the sensor. If it’s a not-so-good lens, resolution improves some, but not as much.)

Photographers in recent years have jumped from 16-megapixel sensors to 36 and even 50 megapixels. Not quite a doubling of resolution, but enough to allow the cameras to see weaknesses in lenses that weren’t apparent before. Mainstream video has moved from 720p (about 1.3 megapixels) to 1080p (about 2.3 megapixels) to 4k (8-9 megapixels) in recent years, so there’s already been a resolution doubling although the resolution is still much lower than for photography.

But now, the higher-end video is 6k (about 19 megapixels) or even 8k (33 megapixels). Video resolution is nearly doubling again, in a very short time. When photo cameras reached 32 megapixels, photographers started seeing flaws in their lenses that the manufacturers didn’t see on their existing testing. I expect the same thing is about to happen with video.

Now 72,934 cinematographers are all going to assume that those more expensive video lenses aren’t going to have the problems that cheaper photo lenses have because they haven’t seen it (yet). And 643 places that test video lenses on charts and projectors are going to tell them they don’t need to worry about it because their tests show the lenses are perfect (so far). And then, one day soon, a cinematographer somewhere is going to look at his high-resolution footage, shot with a lens he’s used many times before at lower resolution, and scream because one side of the image is blurrier than the other.

If you want to stop reading here and go ahead and comment that I’m completely wrong because you just know I must be you may proceed. If not, you can read further, and I’ll give you some introductions to the Cinema lens tests we’ll be publishing in the next few weeks and months.

MTF Full-Field Display Examples

We’ve started using these because they provide a really intuitive way to look at the MTF of a lens. In previous posts, we’ve used the frequency of 30 line pairs /mm because that’s a good compromise between high and low resolutions.

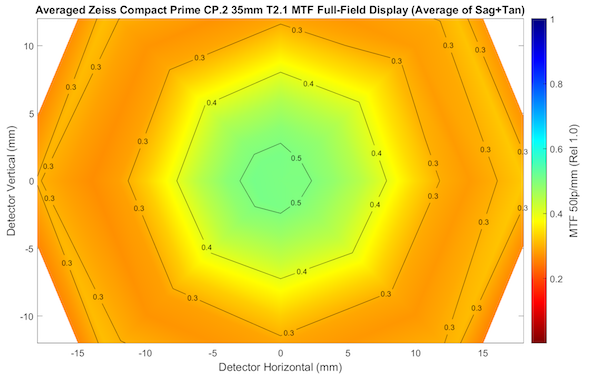

For those of you who don’t speak MTF, only a high-resolution sensor can differentiate high frequencies, like 50 lp/mm. If you’re shooting a 3.2-megapixel image, you don’t see these. If you’re shooting a 30-megapixel image, you definitely can. A high MTF, the blue shades in the graphs below, mean things have high contrast. Low MTF, the red shades in the graphs below, is just a gray smear.

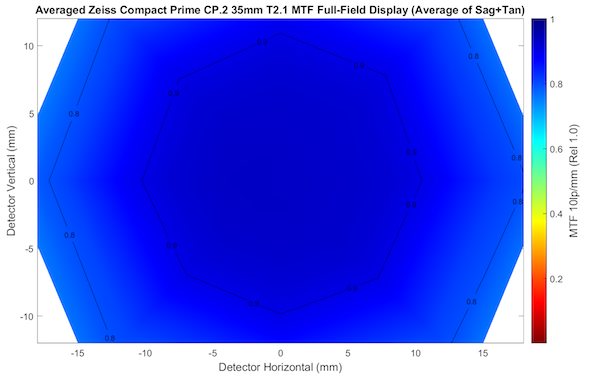

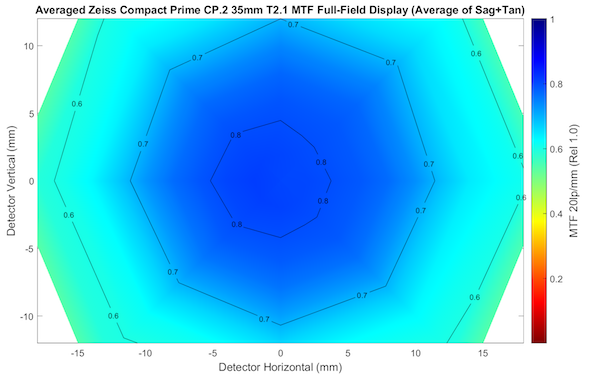

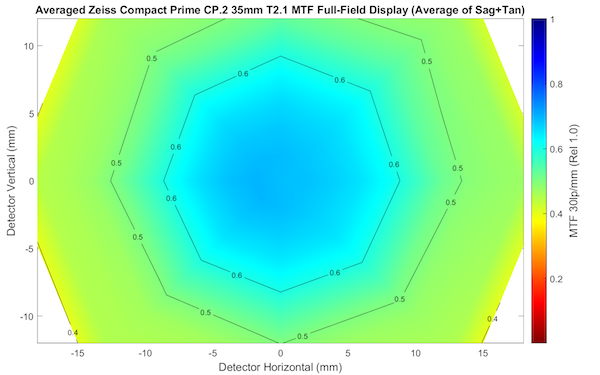

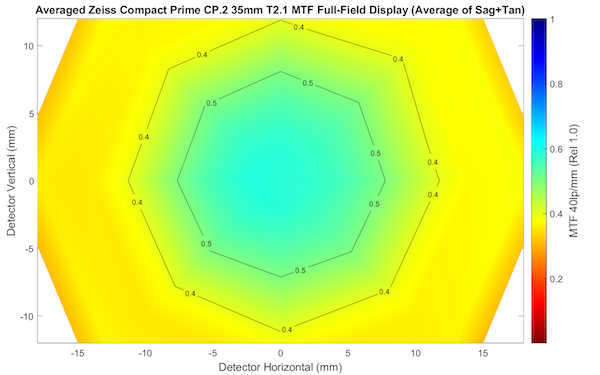

For the examples below I’m going to use a nice Cinema lens that many people have shot with, the Zeiss 35mm T2.1 CP.2 lens. This first set of graphs shows how the average of 10 copies of this lens performs at different frequencies.

10 lp/mm

At low frequencies, the lens is very good. The dark blue means the MTF is very high, and it stays that way from one side to the other.

Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

20 lp/mm

At a slightly higher frequency, things are still good, but you can see that the lens is a little softer away from centers. If you’ve shot with this lens, even at 1080p you’ve noticed this.

Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

30 lp/mm

This is our usual testing frequency, and things look as you’d expect, MTF is lower even in the center now. How would this matter? In theory, if you’re shooting at 1080, you probably would see the same resolution in most decent 35mm lenses, but at 4k, you will start to notice some are better or worse with fine detail. I’m not making any judgment about the CP.2 (yet), just showing that there is room to be better or worse than this lens at higher frequencies.

Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

40 lp/mm

Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

50 lp/mm

At higher frequencies we’re getting a lot of orange now, meaning the lens is just barely handling fine details. Red would be low enough that fine details would be lost if you’re shooting very high resolution video. That may or may not matter a bit to you, just pointing it out.

Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

So That Didn’t Matter Much at All, but This Does.

The images above were averages of 10 copies, and behaved very nicely, just like the lens manufacturer’s data does. But what if we look at individual copies of that lens? Well, that’s where it gets interesting.

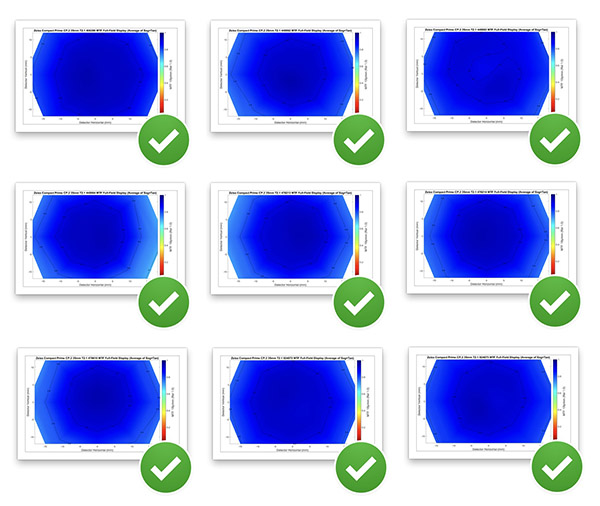

Here are nine copies (because nine fit nicely in the frame) of the 35mm T2.1 CP.2 tested at 10 lp/mm. They all look great and perform nearly identically; you certainly couldn’t see any difference between them shooting 1080p video. (BTW – the green check is just from our software letting us know these files have been backed up.)

Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

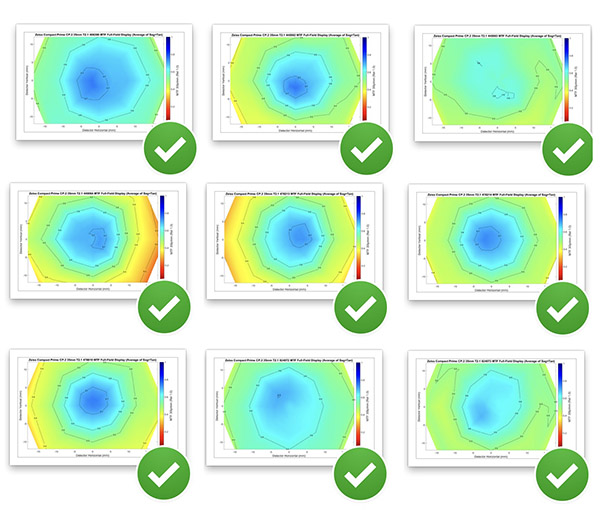

Here are the same nine lenses but this time, shown at 30 lp/mm. At this higher frequency, it’s apparent the lenses are not all identical, although all are acceptable. But on a couple, the very edge is getting unacceptably soft (red areas) and in one (upper right) the center isn’t quite as sharp as the others. Looking at the images above, this difference isn’t very apparent at the 10 lp/mm frequency (these are the same lenses in the same order).

Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

If we look at them at 50 lp/mm we see there’s even more variation.

Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

Does this variation at higher frequencies matter at all? If you’re shooting 1080p video, absolutely not, you can’t see it. If you’re shooting 4k, you probably still wouldn’t notice it. But at 6K or 8K you certainly could.

So What Does It Mean?

Mostly this post is just an introduction to the topic so that when I start showing Cine lens tests, you understand why I’m showing these higher frequencies and whether those frequencies are important to you. And also to explain why I’m saying you may start seeing things you’ve never seen before when you start shooting 6k and 8k.

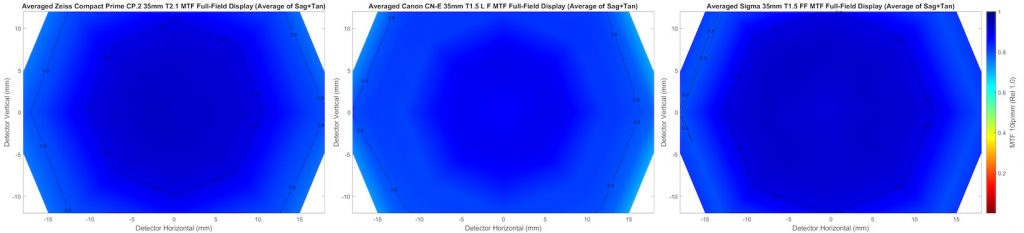

And as people transition into higher resolution video, the differences in lenses will become more important. We’ll be doing a lot of comparisons in future posts, but to give you an idea, the Canon CN-E, Zeiss CP.2, and Sigma Cine 35mm T1.5 have nearly identical performance at low frequencies on average.

Left to right: Zeiss, Canon, Sigma 35mm Cine lenses at 10 lp/mm; Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

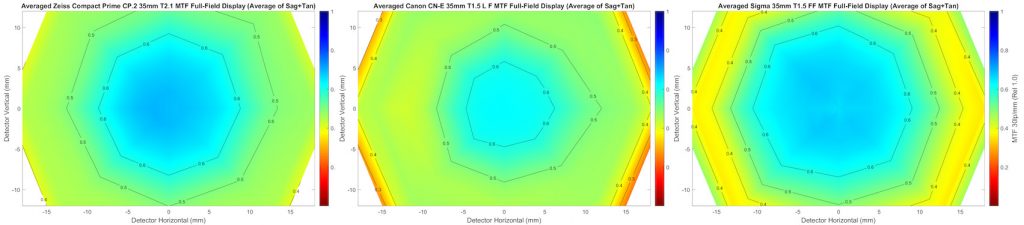

But begin to look a bit different at higher frequencies.

Left to right: Zeiss, Canon, Sigma 35mm Cine lenses at 30 lp/mm; Olaf Optical Testing, 2017

Moreover, as we showed above, variation between lenses is greater at higher frequencies and will be more noticeable on higher resolution sensors.

I just wanted to show why, as we start publishing Cine lens MTF charts, we’ll be emphasizing how the lenses differ at different testing frequencies. Depending on the resolution you’re shooting at it may make a huge difference to you, or none at all.

Roger Cicala, Aaron Closz, and Brandon Dube

Lensrentals.com

July, 2017

. . . .

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Illya Friedman

-

Thomas Achermann

-

Terry

-

Brandon Dube

-

Brandon Dube

-

Brandon Dube

-

Till Ulen

-

KWNJr

-

Ted Miller

-

KWNJr

-

KWNJr

-

David Bateman

-

Brandon Dube

-

Van Forsman

-

Roger Cicala

-

emp11

-

Roger Cicala

-

Stanislaw Zolczynski

-

Roger Cicala

-

pest

-

Santiago Flores