History of Photography

How Potatoes and Gelatin Created Color Photography

Long ago, I wrote articles about the glory days of photography. The days when any photographer worth a damn dabbled in chemical explosives or Bitumen of Judea and spun off side gigs like Lionel toy trains or fashion clothing. Back then your competition didn’t dabble in stealing your photographs, they stole your patents and drank your milkshake.

One of the things I’ve written about was how photography moved from silver plates, to albumin (egg whites) and collodion wet-plate photography. Wet plate photography was a vast improvement, and its increased light sensitivity meant exposure times were shorter compared to a Daguerreotype. But ‘faster’ was still slow, and collodion burned like gasoline when exposed to the slightest flame (and flaming lanterns were the LEDs of the 1860s). Plus, wet plates had to be prepared just before the photograph was taken and developed immediately after. Just like today, people back then wanted simpler, faster, and easier.

The Dry Plate

Several attempts were made to simplify the wet plate process and to allow plates to be made and then stored for future use. Some were sort of successful, but only at the cost of decreased sensitivity or prolonging exposure times (which were already long).

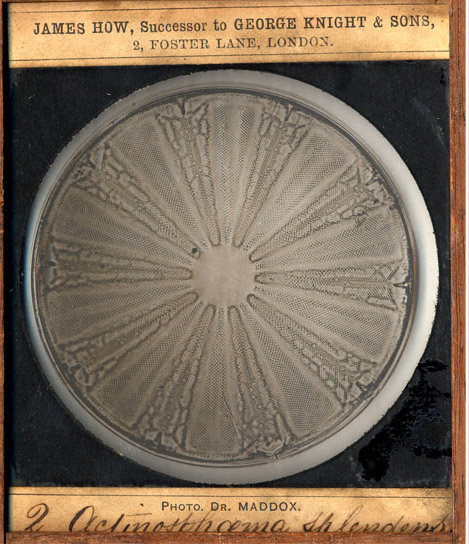

Then along came Richard L. Maddox, who continued the long and illustrious line of physicians improving photography. Dr. Maddox excelled at photo-microscopy (taking photographs of microscopic subjects). Given the limited equipment available in the 1800s, that was a difficult thing to do.

Photomicrograph of a diatom, RL Maddox, 1871

Dr. Maddox complained of health problems his entire life (although he lived to be 86). If you had money in those days, the accepted treatment for being sickly was taking a World Tour, and Maddox’ parents sent him on one starting in 1839. (I can think of no reason travel on a cramped sailing vessel would restore health, so I assume the ‘world tour’ thing was mostly about ‘if you’re in Egypt I won’t have to listen to you complaining all the time.’) He returned to England long enough to qualify for his medical degree, then went back to traveling, sometimes living in England, sometimes abroad, sometimes practicing, sometimes not. But from the 1850s on, he was always photographing.

Richard Maddox, circa 1871. He does look rather ill. Image modified from Geschichte der Photographie in Bildern, Tafel 2: Richard Leach Maddox (1816–1902) the University of Heidelberg.

Maddox’ photomicrographs had a superb reputation in scientific circles. But he found that the fumes from creating and developing collodion wet-plates adversely affected his health, so he began experimenting to find an alternative to collodion. He tried ‘various gummy vegetable matters’ and ‘starches from rice and tapioca’ among other things, but they all failed.

Eventually, he ran down to the market, bought a packet of Nelson’s Gelatine Granules (seriously), and found this coated glass quite well. Finally, he simplified his methods, mixing both bromide and silver nitrate in warm gelatin, coating the plates, and letting them dry. This was a huge advantage; you could make a batch of plates and store them for future use. You also didn’t need to develop them immediately after exposure, so you didn’t have to travel with a portable dark room. Maddox’s plates made images that weren’t very contrasty, though, and the coating was very delicate.

Maddox published his methods in 1871. Like Frederick Scott Archer (who developed the collodion wet-plate), he let others use his technique freely and never filed for a patent. Like Archer, Maddox lived his old age in poverty and photography societies took up collections for him. He claimed that a financial adviser had robbed him; others said his wealthy father did not include him in his will. Both may be true.

John Burgess and Richard Kennet made some chemical modifications to Maddox’s formula and attempted to market dry plates with limited success. Charles Harper Bennett developed a method to harden the coating and in 1878 found if he heated the gelatin plates the emulsion became more sensitive to light. Bennet’s plates exposed several times faster than wet plates or the previous dry plates. In fact, exposures on a sunny day could now be made in a fraction of a second.

Bennet and his partner, Charles Fry, began mass producing and selling dry plates, bringing photography to the masses. In possibly the grossest bit of marketing ever done, Bennet demonstrated just how fast his plates were by strapping some dynamite to a mule, blowing it to bits, photographing the mule pieces in mid air, and publishing it in Scientific American.

Source unkown

George Eastman, of later Kodak fame, visited Fry and Bennet. He went home, made better machinery to mass-produce dry plates, and eventually developed methods for placing the emulsion on film, rather than glass. By the 1880s, photography became something everyone could do, causing photographer Charles Dodson (aka Lewis Carroll) to famously remark “Somebody just let the rabble in” and give up photography altogether.

Don’t You Have Some French Guys to Talk About? You Usually Talk About French Guys.

Of course, I do! Partly because the French started photography but mostly because they were primarily bat-shit crazy, like Nadar, and therefore are much more fun to discuss. But speaking of crazy Frenchman, before I get on with the story, there’s an aside, and you know I love my asides. A microscopist cohort of Maddox, John Benjamin Dancer, did the opposite of Maddox. Instead of making big pictures of microscopic stuff, he made little pictures of big stuff.

His claim to fame was reducing a photograph of ‘the 680-word tablet erected in memory of William Sturgeon to a positive photograph 1/16 of an inch in diameter’. If you viewed the tiny photograph under a microscope, you could then read the entire tablet. Why did he spend years learning how to take a picture you could see and turn it into a picture you could only see through a microscope? Who the hell knows. He was into photography and microscopes so why not? Plus he was probably bat-shit like the rest of them. (One must consider that everyone doing photography in those days was inhaling a lot of fumes in the darkroom. It’s probably no coincidence they ‘weren’t quite right’ as we say in the South.)

What has this got to do with crazy Frenchmen (who weren’t any crazier than the above Englishman)? Well in 1857 Dancer’s tiny photographs were exhibited in Paris, and Rene Dragon saw them. He started playing around with making tiny photographs himself, but he also made simple magnifying viewers so people could look at them without microscopes. He then took an exhibition of his work to London in one of those “You don’t frighten us, English pig-dogs” moments of Franco-British diplomacy.

A year or two later Dragon and Gaspar (who took the first aerial photographs from balloons) were hanging out in Paris when Prussian armies surrounded the city, cutting off communication with the outside world — like Hunter S. Thompson said, ‘when the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.’ While everyone else was trying to find food and shooting at the Prussians, Dragon used his process to shrink down volumes of documents to tiny size, Gaspar put them in hot air balloons and on carrier pigeons. Pretty soon Paris was not only communicating with the outside world; they had a microfilm mail service. From that moment on, microfilm became the favorite high-tech tool of the military, spies, and librarians.

Roger, Are You Ever Going to Get to the Potatoes?

What? Oh, yeah. I got off track a bit. So where were we?

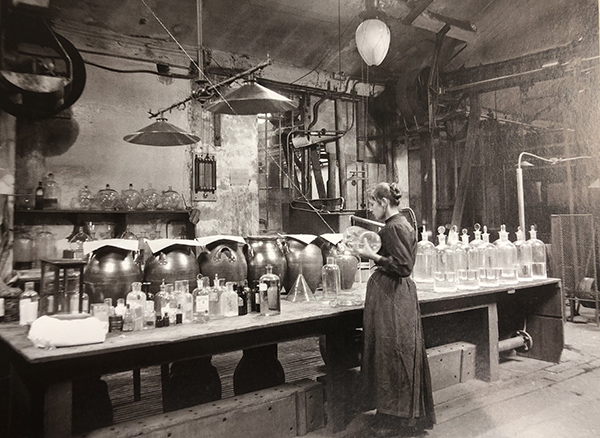

Oh, yeah. So, Bennett and some others were making dry plates in England, and Eastman was doing the same in the U. S. In France, a portrait photographer named Antoine Lumiere saw the writing on the tintype and started to transition from photographer to dry-plate manufacturer. None of the other manufacturers were sharing their secrets, so Antoine used trial and error to try to make good plates. He failed, but his two teenage sons, Louis and Auguste, were more scientific-minded and figured the techniques out.

The Lumiere brothers, source and date unknown.

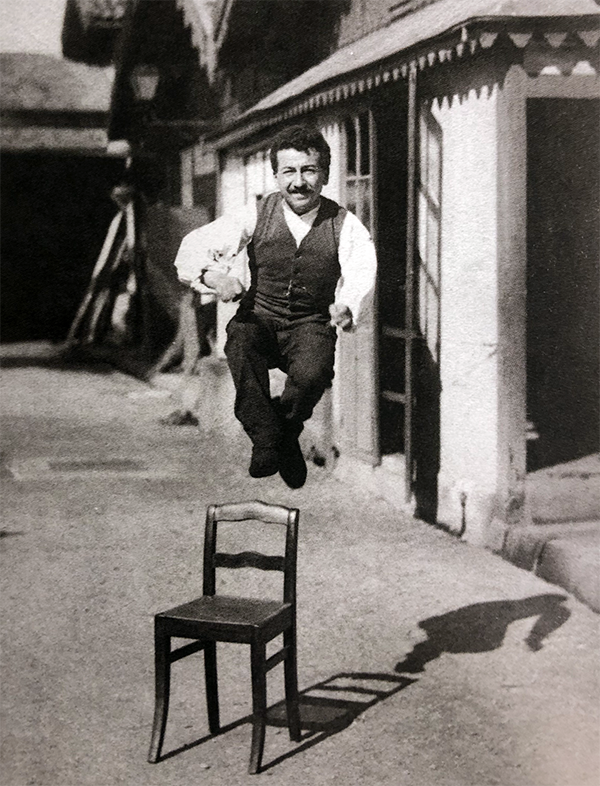

Lumiere plates started with a decent reputation locally, and in 1881 Louis found a new formula, which they called ‘Blue label’ plates, that gained a widespread reputation for excellence. Exhibiting far better taste than Bennett, they used a photo of August jumping over a chair to demonstrate how fast their emulsion was.

August jumping, 1888, by Louis Loumiere

The Lumieres continued to expand both in size and in products, producing glass dry plates, film, and chemicals for developing. By 1890 they were probably the largest dry plate manufacturer in Europe, and exported film to most of the world. (The exception was the United States, which imposed high tariffs on photographic equipment.)

The growth of the Lumiere company occurred during a golden age of photography; the 1890s and early 1900s. Dry plates let large format photographers do all kinds of things they hadn’t done with wet plates and photography expanded. But the film allowed a whole lot of amateurs to create decent images. The work of professional photographers was devalued, and expensive large format supplies suffered decreased demand. Sound familiar? Understandably, the Lumieres looked for ways to expand their business.

In 1894 Antoine went to an exhibition of Edison’s Kinetoscope in Paris. The Kinetoscope could only let one person at a time view a film through a peephole.

Edison Kinetoscope, source unknown

Within a year the brothers developed the Cinematographe. It was much smaller than a Kinetoscope, could project a film onto a screen, and also function as a motion picture camera.

Lumiere Cinemetagraphe, 1895. Image courtesy Science Museum Group

The Lumieres showed what is considered the first projected motion picture, “La Sortie des ourvriers de l’usine Lumiere” (Workers Leaving the Lumiere Factory) in 1895. The Lumieres sent cameramen out to record scenes of everyday French life and newsworthy events. They opened Cinematographe theaters in several cities and made over 40 short films.

Image from public domain

Despite projecting the first short film, and contributing significantly to the development of motion pictures, they exited the field fairly quickly. Louis is said to have remarked, “Cinema is a novelty without a future.” The early history of motion pictures would make a good (and fairly long) article by itself, but that will have to wait for another post. We’re here to talk about how potatoes changed photography and documented the world.

Experiments in Color Photography

One of the reasons the Lumieres dropped motion picture development is that they thought color photography had a bigger future. There were some known methods for making color images at this time. James Clerk Maxwell had demonstrated making filtered ‘color separations’ and combining the images, and several people had tried to simplify his process. Some chemicals that did reproduce colors after exposure had been discovered, although they weren’t accurate and faded quickly.

Physicist Gabriel Lippman developed an ingenious method that used the interference patterns of different wavelengths of light to reproduce color, but it was technically difficult (it required a very fine and exceedingly thin emulsion), needed hours of exposure time, and very specific viewing conditions. It was considered a technique only suitable for the laboratory; the principles were more like creating a hologram than taking a photograph. It did make accurate color photographs, however.

To show you how big a deal this was, Lippman won the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physics for creating a color photograph. He beat out Ernest Rutherford (who discovered atoms were made of smaller particles), Max Plank (of Plank’s constant and quantum mechanics fame), and Guglielmo Marconi (who discovered radio). Lippman later invented integral photography, which we call light field photography today.

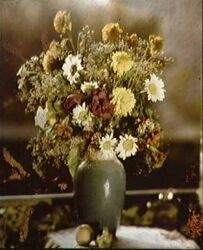

Lippman color image of flowers, circa 1890. From the public domain.

The Lumieres, explored all three methods of creating color images. Because the Lippman process was limited by the technical difficulties of making very fine-grained emulsions of very exact thickness, it seemed the method their expertise would be best suited to explore. By 1893, the Lumieres had improved the process so that the exposure time for a Lippman image (which had been hours) was reduced to about 30 minutes.

By the end of that year, they had shortened it to a few minutes (they even mad a color portrait that they showed at the Paris Photo Club) and began to manufacture Lippman plates. The process of creating an image was still very exacting and difficult, and even viewing the images required special lighting and equipment, so it remained mostly a curiosity.

The Lumieres also explored making color images through three-color separations, combining the three images onto a single glass plate for viewing. They patented a process in 1895, calling it ALL Chroma (ALL stood for August and Luis Lumiere). ALL Chroma created images with absolutely vivid color and preserved fine detail that was lacking in a Lippman image.

“Bouquet of Flowers”, Gabriel Veyre, 1895. Lumiere ALL Chroma process.

The process was technically quite difficult, though, and required a lot of practice to master. The cost of the plates made getting sufficient practice financially impossible for most photographers. The Lumiere company maintained a studio and made stereoscopic color images that they distributed widely as a marketing tool for a few years, but they sold very little ALL Chroma.

Still life of flowers and ferns; Lumiere Brothers; 1907; All-Chroma autochrome; 7 x 6.7 cm 2 3,4 x 2 5,8 in. Single use license from Amay, may not be reproduced.

The Autochrome

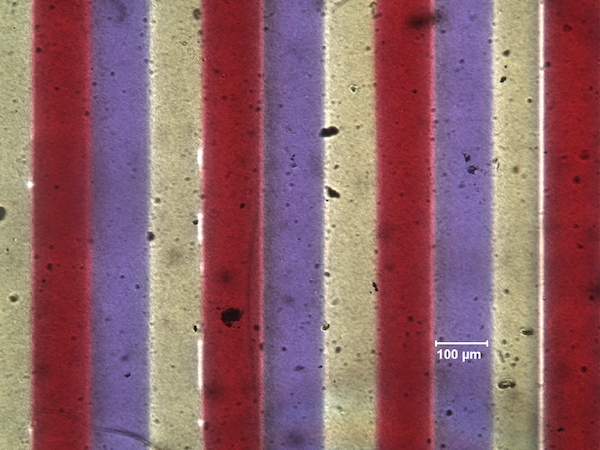

The Lumieres realized they needed a simpler method to obtain color photographs if they were going to sell anything. The idea of microscopic separation of colors on the photo plate had been around for a while, although technically it remained impractical. Most attempts used a screen of colored lines or squares laid over the photographic plate. Given the size of the screen elements (0.1mm or more), the resolution was markedly reduced.

Microscopic view of a Joly color screen. This was placed over a plate to create a color image of poor resolution. Gawain Weaver, Weaver Art Conservation, San Anselmo, CA

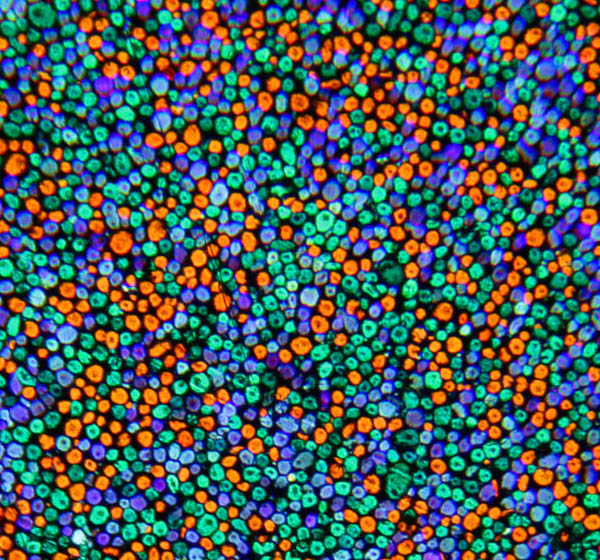

Luis solution was simple and elegant; he would cover the emulsion with small, dyed granules to serve as a color filter (similar to the way the Bayer filter works in a modern digital camera). To preserve resolution, he knew he needed very small granules that were easy to dye. He examined dozens of different substances: plant starches, glass dust, and several varieties of yeast. Rice starch was his first choice, because of very small grain size (.005mm), but it didn’t absorb dyes well. Potato starch granules were nearly as small ( 0.01mm or less), and absorbed dye easily, so they were his eventual choice.

The starch granules he could obtain commercially varied in size far too much for what he planned. He hired M. Demure to design a processing plant that could produce grains that were all 10 to 15 microns in diameter. Eventually, 12,000 kg of potatoes were processed per day, yielding about 5,000 kilograms of properly sized starch granules.

Then there was experimentation to choose the right color dies (eventually orange-red, green, and violet dyes were chosen). Finally, he had to create techniques to apply the dye granules, flatten them, apply the silver emulsion, and seal everything for stability. That Luis accomplished all this in just a few years is remarkable. This process gave over 4,000,000 “pixels” per square inch, far more than the other ‘colorizing’ techniques that were developed around this time.

Microscopic image of an Autochrome plate. Public domain

They patented and introduced their Autochrome plates in 1907. The plates could be used in the existing cameras of the day, although developing the plate was more complex than developing a monochrome image. The original development had 14 separate steps. Simpler developing methods were developed over the years, as well as modifications of development techniques to emphasize and correct colors.

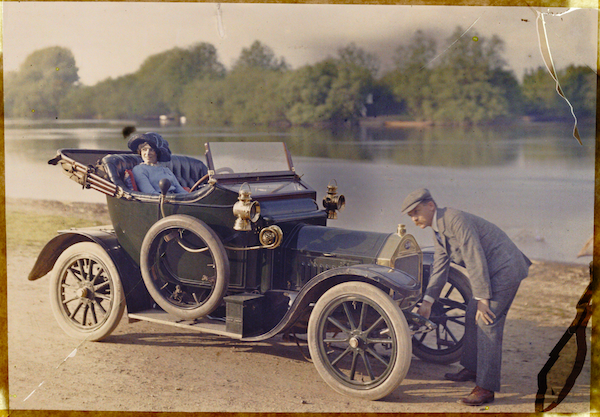

From their introduction, until the early 1930s (when Kodachrome and Agfa tri pack film was released), Autochrome was THE method for making color images. The high cost and complex processing kept it out of reach of most amateur photographers. But for 25 years, if you saw a color photograph, it was probably an Autochrome.

Couple with a motor car, photographer unknown, circa 1910

Flower Study Baron de Meyer, 1908

So there you have it: add some potato starch to gelatin dry plates and, poof, color photography.

Albert Khan’s Archives of the Planet

The Lumiere Autochrome story was really just a blip in the photography business world. It never accounted for more than a fraction of their revenue and their business steadily declined even after its introduction. The real importance is that for over two decades, it accounts for almost every color photograph that exists. One reason for that is largely because the Autochrome was developed in France it quickly came to the attention of another Frenchman.

Albert Kahn was a wealthy French banker who traveled the world for fun and profit, occasionally taking some pictures during his travels. In 1909 he saw Autochrome images and decided he wanted to document the entire world in color pictures. His goal was to preserve ‘the aspects and practices of human activity which will inevitably disappear over time’.

From 1909 to 1929 (he went bankrupt in the Crash of ’29) he sent photographers on expeditions to over 50 countries, amassing over 72,000 images and 183,000 meters of film. Much of that collection, The Archives of the Planet, is now available in open source data and geolocated on a nice website. It’s truly an amazing archive and if you’ve made it through this long post, consider this link your reward: http://collections.albert-kahn.hauts-de-seine.fr/

To whet your appetite, I’ll close with just a few of them.

Avion de bombardement, Le Tronquoy, Somme, France, 1916, (Autochrome, 9 x 12 cm),

Stéphane Passet, Département des Hauts-de-Seine, musée Albert-Kahn, Archives de la Planète, A 7 242 S

La messe aux tranchées de premières lignes, Le Hamel, Somme, Picardie, France, 9 août 1915, (Autochrome, ),

Stéphane Passet, Département des Hauts-de-Seine, musée Albert-Kahn, Archives de la Planète, A 5 938

, Niederbruck, Haut-Rhin, Alsace, France, 4 juillet 1918, (Autochrome, ),

Georges Chevalier, Département des Hauts-de-Seine, musée Albert-Kahn, Archives de la Planète, A 74 083

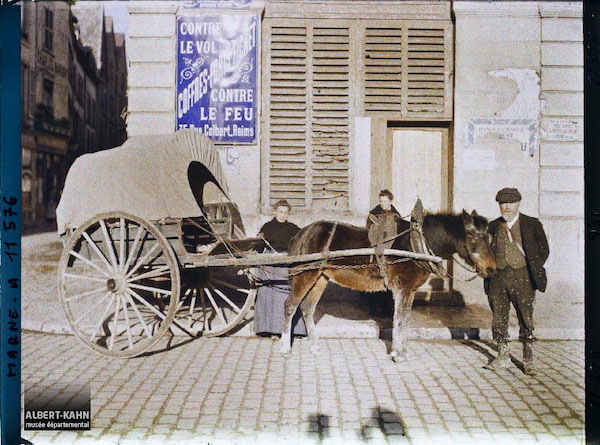

, Reims, Marne, Champagne, France, 1917, (Autochrome, ),

Paul Castelnau, Département des Hauts-de-Seine, musée Albert-Kahn, Archives de la Planète, A 11 576

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

May, 2019

References:

- Lavedrine, B and Gandolfo, J: The Lumiere Autochrome. Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles, 2013

- Lippmann, G. (1891) ‘La photographie des couleurs’, Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences 112, pp. 274-275.

- Lippmann, G. (1892) ‘La photographie des couleurs [deuxième note]’, Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences 114, pp. 961-962.

- Lumière, A. & L. (1893) ‘Sur les procédés pour la photographie des couleurs d’après la méthode de M. Lippmann’, Bull. Soc. franç. Phot. (2o série) 9, pp. 249-251.

- National Science and Media Museum: The Lumiere Brothers: Pioneers of Cinema and Color Photography. https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/the-lumiere-brothers-pioneers-of-cinema-and-colour-photography/

- Newhall, B, et al.: History of Photography. Development of the Dry Plate. https://www.britannica.com/technology/photography#ref416426

- Okuefuna, D: The Dawn of Color Photography: Albert Kahn’s Archives of the Planet. Princeton University Press. 2008

- Pruitt, S: The Lumiere Brothers, Pioneers of Cinema. https://www.history.com/news/the-lumiere-brothers-pioneers-of-cinema

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.

-

Michael Clark

-

Roger Cicala

-

intrnst

-

Roger Cicala

-

intrnst

-

Carleton Foxx

-

Roger Cicala

-

Carleton Foxx

-

Athanasius Kirchner

-

Jim A.

-

Renaud Saada

-

Ken Owen

-

KeithB

-

Not THAT Ross Cameron

-

Mike Earussi

-

Nqina Dlamini

-

Dave Hachey

-

Roger Cicala

-

Lee Wooten

-

Cecil Thornhill

-

Ben Rubinstein

-

Andreas Werle

-

Robert Tilden