Roger's Corner

Iceland Spar: The Rock That Discovered Optics

Every year, I can’t think of anything I want for Christmas. So this year, I was pretty excited to come home and tell my wife, “I know exactly what I want for Christmas. A nice big piece of Iceland spar.” I even sent her a link to make it easy. (It’s certainly a comment on our times that I sent a text link across the room to my wife.)

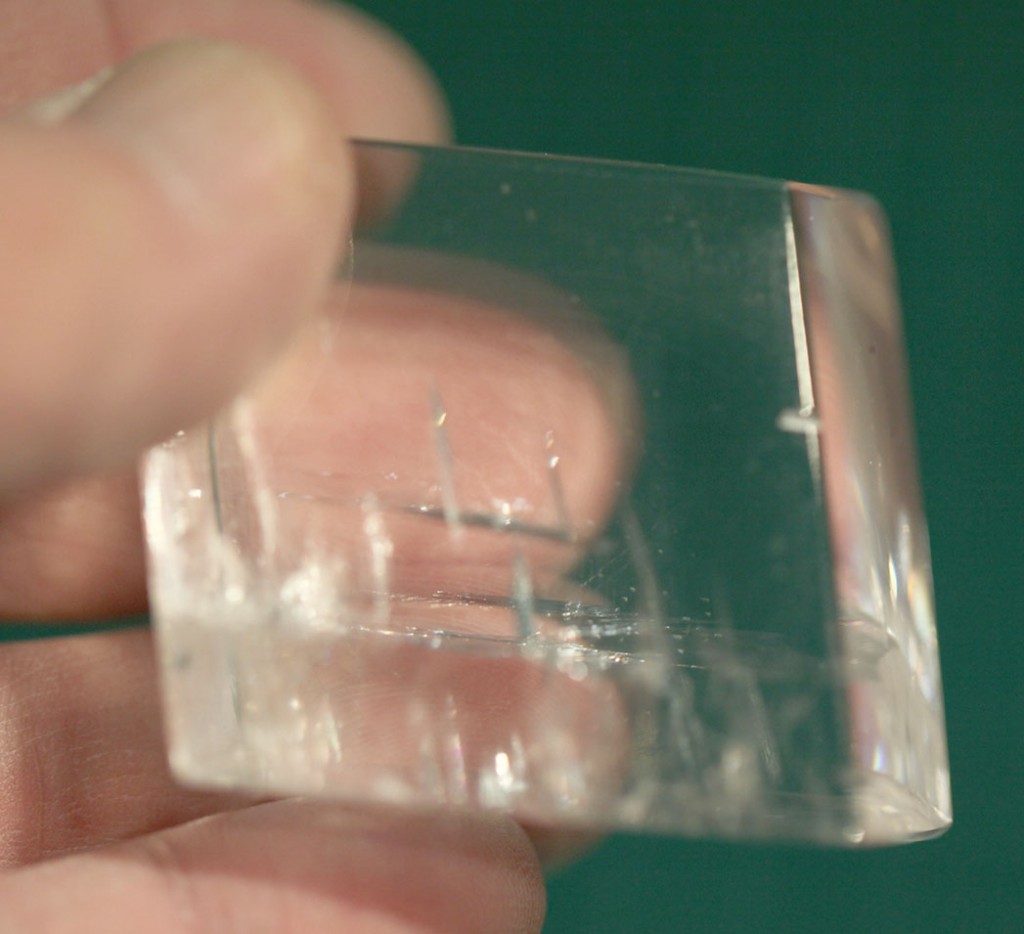

- It’s not motion blur, it’s Iceland spar!

“Really? You want a $100 rock for Christmas?” she asked. I considered mentioning that the price of the rock I want is a tiny fraction of the price of the rock she wants, but thought better of it because she was giving me that look she gives me sometimes. You know, the look that says she knows that at some time there was some reason she chose me, but at this moment she can’t remember when that time was nor that reason.

Instead, I started to explain how Iceland spar is probably the coolest, most important substance ever. How the Vikings probably used it to find America. How Iceland spar was a key to discovering what light actually was. That every great name in optics from Huygens, to Newton, to Fresnel, and even Edwin Land (of Polaroid fame) used Iceland spar. How a shortage of Iceland spar in the late 1800s was considered an emergency by almost every industrial nation. That Iceland spar helped win World War II and can make things invisible.

Of course, before I could tell her even half of that stuff, she rolled her eyes and wrinkled her nose the way she does when the dogs or I bring something into the house that she feels would best be left outside to further decompose. She did look at the link I sent, though, because she asked, “Why does something called Iceland spar come from Mexico?”

I’m pretty sure she wasn’t particularly interested in the answer, because she immediately started talking to herself. Something about whether there were mature, grown-up males anywhere on the planet. My response, that they raised unicorns near Atlantis, apparently has created enough ‘alone time’ for me to write this post and tell you all the cool stuff I didn’t get to tell her. And to order a piece of Iceland spar, because I’m fairly certain it won’t be under the tree.

So, What is Iceland spar?

Iceland spar is a crystal of calcite (calcium carbonate). Calcite is a fairly common mineral and comes in a spectacular range of colors caused by the impurities it contains.

- http://gwydir.demon.co.uk/jo/minerals/alphabet.htm

Iceland spar is rather unique among the calcites. It contains no impurities, so it’s nearly colorless and transparent to both visible and ultraviolet light. For centuries, the only source of this pure calcite was located near Reydarfjördur fjord in eastern Iceland, hence most of the world called it Iceland spar (spar means a crystal with smooth surfaces). The Icelanders just called it silfurberg, meaning silver rock.

A crystal of Iceland spar has two very interesting properties. First, it is a natural polarizing filter. Second, because of its natural polarization, Iceland spar is birefringent, meaning light rays entering the crystal become polarized, split, and take two paths to exit the crystal – creating a double image of an object seen through the crystal.

There is good evidence that the Vikings used the polarizing effect of Iceland spar to navigate the North Atlantic. The constant fog and mist in the North Atlantic often make navigation by stars or sun impossible. The Vikings called Iceland spar a ‘sunstone’ because the polarizing effect can be used to find the direction of the sun even in dense fog and overcast conditions. It can even find the direction of the sun when the sun is actually below the horizon, as happens when you’re sailing above the Arctic circle.

- The polarizing effect of Iceland spar can accurately locate the sun even through heavy clouds or mist. If you’re a Viking. I’ve tried it and had no success at all. Credit: ArniEin, WIkipedia Commons

The second interesting feature of Iceland spar is birefringence, meaning it refracts light into two separate images, is more noticeable. The double image may just seem mildly interesting to you and me. But it turned the scientific world (at least the optical part of it) upside down back in the 1600s.

- A piece of Iceland spar on my worktable, doubly refracting the gridlines.

Iceland Spar and the Theories of Light

Rasmus Bartholin of Copenhagen made the first written reports about Icelandic spar in 1669. At the time, Snell’s law of refraction were well known. Snell’s law said a regular crystal would bend light rays a given amount and there was a nice formula to calculate that amount. But Bartholin’s report showed that Iceland spar bent light two different amounts, creating two different images. This seemed to break Snell’s law.

Within a few years, Bartholin’s findings had been discussed throughout Europe and scientists (they would have called themselves natural philosophers back then) were begging for samples of Iceland spar. (They had to beg from people in Denmark, like Bartholin, because Iceland was part of the Danish Kingdom.) Among those begging were Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton.

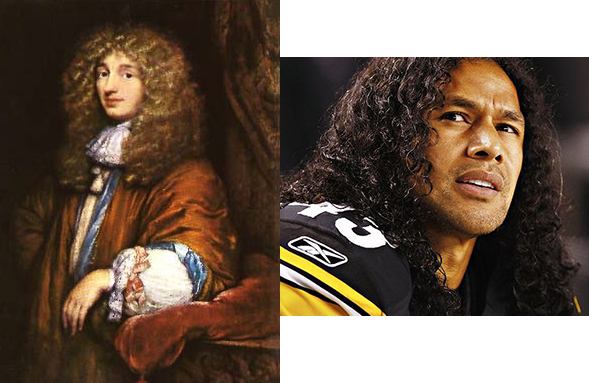

Christiaan Huygens, in addition to originating Troy Polamalu’s hair cut, was an amazingly brilliant and productive man. He discovered the formula for centripetal force, invented the pendulum clock and the pocket watch, and discovered Saturn’s rings and largest moon (Titan) as well as the Orion nebula.

- Christiaan Huygens (left) and Troy Polamalu. Coincidence?

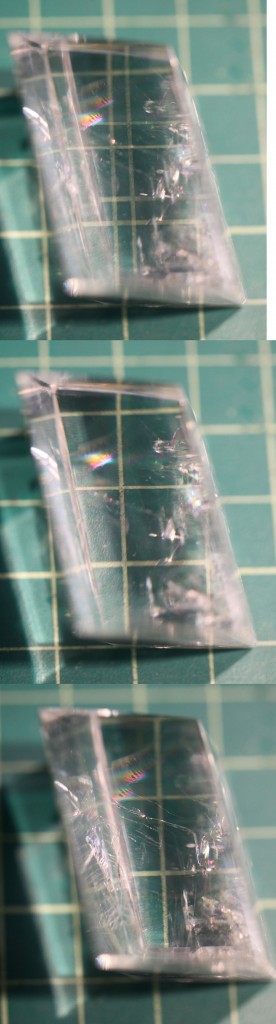

Huygens spent over a year experimenting with Iceland spar after Bartholin sent him some samples. He discovered that putting a second piece of Icelandic spar over the first piece didn’t make 4 images out of the two seen through the first piece of spar. In fact, by rotating a second piece over the first, he could make either of the original two images disappear.

The reason, we now know, is that Iceland spar is a natural polarizer. It splits the incoming light into two polarized beams, making two images. By using a second piece of Iceland spar he could block either of the polarized images originating from the first piece. I don’t have a second piece of Iceland spar handy, but I can do the same thing Huygens did by putting a polarizing filter on my lens. Depending upon which way I rotate the polarizer I can eliminate either one of the refracted images.

- Image through Iceland spar (top), and then two images taken with polarizing filter.

Huygens decided the two refractions were best explained by considering light a spherical wavefront; that the crystal separated the waves in two slightly different directions because of different velocities of the waves. He developed formulae mathematically describing the geometry of such waves, which originated much of modern geometric optics. Unfortunately, his wave theory of light was not widely accepted at the time, partly because his longitudinal waves did not really explain birefringence very well. His formulae for geometric optics were accepted, though, because they generally worked.

Isaac Newton had already determined that white light is made up of various colors and that the different colors refracted different amounts (what we now think of as chromatic aberration). He had decided that light was not waves, but rather ‘corpuscles’ or particles (which is also correct). He proved that Huygens wave theory could not really explain the double refraction of Icelandic spar. Instead, he claimed, birefringence occurred because light particles had two sides, and the crystal separated those sides. Newton couldn’t prove this, of course, but his reputation being what it was people generally accepted it for the next 100 years or so.

- Isaac Newton

Iceland spar, then, contributed to the original development of both the wave and particle theories of light as the great optical scientists of the day tried to explain birefringence. Oddly enough, neither theory explained birefringence very well. At the time, both theories were partially correct and partially incomplete. They would remain that way for over a century until Thomas Young came along.

Young definitely proved the wavelike nature of light in 1801 in a series of experiments that (unfortunately) had nothing to do with Iceland spar. Soon after that, though, a French scientist, Etienne Louis Malus, noticed the polarizing effects of Iceland spar when he rotated it and looked at sunlight from various angles. He experimented with it and eventually developed Malus’ Law, which predicts the strength of a beam of polarized light when passing through another polarizer.

A decade later, both Young and Augustin-Jean Fresnel (of Fresnel lens fame) finally explained the polarization of Icelandic spar. When they thought of light waves as transverse (like ripples in a pond) not longitudinal (like a slinky), then polarization of the waves was possible, explaining the birefringence of Iceland spar. It was nearly 150 years after Huygens that Young and Fresnel finally developed a wave theory of light that explained polarization and birefringence.

Using Polarized Light

Once there was a good understanding of how Iceland spar polarized light, it wasn’t long before people put this new knowledge to practical use. With simple pieces of Iceland spar, scientists of the day discovered that the atmosphere polarized sunlight, that light from a comet’s tail was polarized, moonlight was partially polarized, and certain chemicals in solution were also polarized.

The Nicol prism was invented in 1828 by, not surprisingly, William Nicol. It consisted of two wedges of Icelandic spar joined together with a layer of Canadian balsam. When light is shined in one end the spar split the beams. Because of the two angles of refraction, one beam exits the end of the prism as polarized light. The other was refracted outside the prism and absorbed.

- Nicol prism: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/

The Wollaston prism was aligned somewhat differently and emitted two beams of polarized light. Dozens of other types of polarizing prisms were developed over the next few years.

- Wollason prism. Fgalore, courtesy Wikipedia commons.

Scientists now had a source of polarized light to play with, and play with it they did. Photometers and spectrophotometers (instruments that measured light intensity and character) were developed. They were used both in pure scientific research and in the chemical industry. Polarimeters (instruments that measures the change of polarized light passing through solutions) detected the presence of, and measured the concentrations of, specific chemicals in solutions.

Chemical synthesis, extractions, and purity analysis exploded in the mid-1800s, largely because of these instruments. The sugar industry was rife with fraud before the development of polarimeters, but once they became available accurate measurements of sugar concentration could be made. Chemists could accurately assay concentrations for the first time, allowing them to purify numerous substances. Medicines changed from ground herbs of unknown concentration to purified preparations with known potency.

Late 1800s Polarimeter. http://antiquesci.com/

Polarized microscopes were used in biology and medicine, but also in geology to assess the authenticity of gems and crystals. For photographers and astronomers, crossed polarizers were used to assess optical glass and lenses. Flaws and defects in the glass which were invisible to visual inspection showed very clearly when examined by polarizers.

There were even early attempts to use Iceland spar to create 3-D imaging. In 1894, a British physicist named John Anderton patented a system that would project paired images through magic lanterns each equipped with Nicol prism polarizers in different orientations. A viewer with opposite oriented prisms would reproduce a 3-dimensional image. While the system would work in theory, it was probably too bulky and expensive to ever gain widespread use. (Edwin Land created a similar system in the 1930s with his polarized film.)

Every one of these scientific instruments used prisms made of Iceland spar to create polarized light. Iceland spar was no longer a scientific curiosity; it was a major industrial component used in thousands of measuring devices. With only one source of the crystals, it wasn’t surprising that significant shortages of Iceland spar occurred. The situation became so severe that European instrument makers got the governments of Germany and France to request increased mining in Iceland, but the mine there was nearly exhausted.

New sources were found first in South Africa and later in Mexico, the U. S., and South America. Even with these new sources, the supply was always limited. Worldwide mining produced a few tons of optical grade Iceland spar, at most, each year. For example, the mine at Taos County, New Mexico produced 850 pounds (not tons, pounds) of Iceland spar in 1939.

Iceland spar Goes Modern

Edwin Land’s invention of polarizing sheets and films in 1928 helped alleviate the Iceland spar shortage, although polarizing film was only useful in certain applications. Some other polarizing crystals, both natural and artificial, were also developed. But Iceland spar continued to be used in a variety of optical instruments and remained in great demand throughout the 20th century.

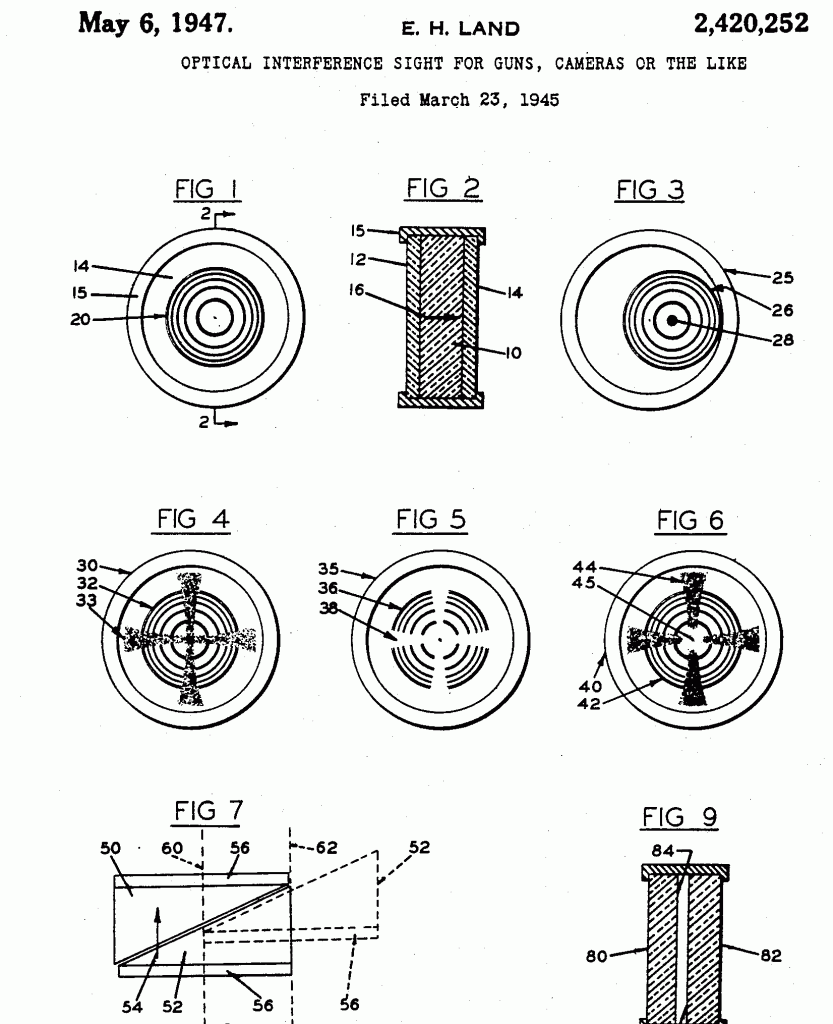

By an interesting coincidence, Edwin Land created some of this demand. When the United States entered World War II, one of its first needs was a small, accurate gun sight for its warplanes and anti-aircraft guns. Aerial gun sights at the time were large bulky affairs with prisms and lenses. Land invented the optical ring sight, which consisted of two sheets of polarizing film and two optical wave plates sandwiching a crystal of Iceland spar. Iceland spar was considered a strategic resource by the U. S. government, which had classified studies done assessing the Iceland spar mines of South and Central American nations.

Drawings from US patent 2420252-0 for a polarized 'ring sight'. When the target is in position the polarization shows active crosshairs.

Optical calcite polarizers are used today as polarizers and beam-splitters in the the laser and fiberoptics industries. You can still find devices that contain Nicol and Wollaston prisms today, but the most common current use of calcite crystals is in Glan-type prisms. These can withstand very high luminance and are used to polarize laser light. Quartz and synthetic materials can be used in many, but not all of these applications, and synthetic calcite remains expensive and difficult to produce. Most of the optical calcite crystals used today are mined just like they were in the old days, which is why Iceland spar crystals remain rather pricey.

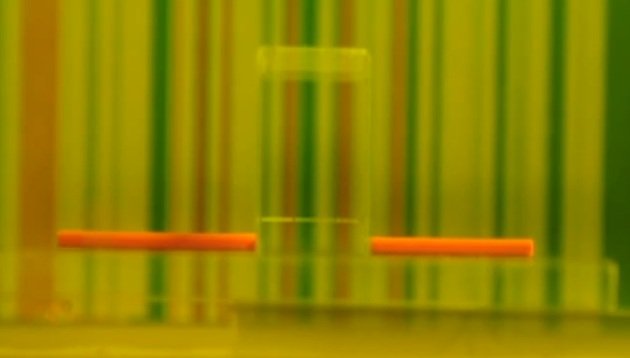

Perhaps the most interesting modern research using optical calcite is to actually make things invisible. Researchers have found that using a pair of shaped calcite crystals in certain media, they can effectively make small objects disappear in visible light. Light from behind the object bends right around it while passing through the two crystals. Viewed from the front it’s as if the object isn’t there. If you haven’t seen it, there’s a video of it as demonstrated at the 2013 Technology, Education and Design Conference HERE. It’s pretty amazing.

- Using two calcite crystals in certain media makes the object between them (a rolled up pink post-it note in this case) disappear. Credit Baile Zhang, Nanyang Technological University

So There You Have It

Obviously I’ve managed to get one piece of Iceland spar. But I wouldn’t mind a second, so it’s still on my Christmas list. Maybe I could do some fun tricks with disappearing lines and such. Until then we’ve already put the original piece to good use topping the Lensrental’s Tech Room Christmas Tree.

And if there’s an optical geek on your Christmas list – well, now you’ve got a great idea for an original gift. You can get them a nice piece of Iceland spar. And just think how much fun it will be when they ask what it is and, armed with this post, you can smugly tell them geeky stuff they didn’t know.

Roger Cicala

Lensrentals.com

December, 2013

Author’s Note: A few weeks ago someone said to me, “Why don’t you go write an interesting blog post about a rock, or something.” Challenge accepted.

References:

Abrahams, Peter: The Testing of Telescope Optics in Historic Times. Presented to the 1994 Convention of the Antique Telescope Society.

Eric Greene: Iceland spar.

Fries, Carl: Optical Calcite Deposits of the Republic of Mexico. United States Department of the Interior. Bulletin 954-D

Leó Kristjánsson: Iceland spar and it’s influence on the development of science and technology in the period 1780-1930. 3rd Edition. University of Iceland. 2010.

Leó Kristjánsson:Iceland spar and its Legacy in Science. Hist. Geo Space Sci., 3, 117–126, 2012

Ropars, G, et al.: A depolarizer as a possible precise sunstone for Viking navigation by polarized skylight. Proceedings of the Royal Society, Nov. 2011.

Vanderwerf, Dennis: Applied Prismatic and Reflective Optics. Chapter 3: Polarization Properties of Prisms and Re?ectors. SPIE, 2010.

Xianzhong Chen, et al: Macroscopic Invisibility Cloaking of Visible Light. Nat Commun. 2011 2: 176.

Author: Roger Cicala

I’m Roger and I am the founder of Lensrentals.com. Hailed as one of the optic nerds here, I enjoy shooting collimated light through 30X microscope objectives in my spare time. When I do take real pictures I like using something different: a Medium format, or Pentax K1, or a Sony RX1R.