Recommendations

What Sensor Size is Best for You as a Videographer?

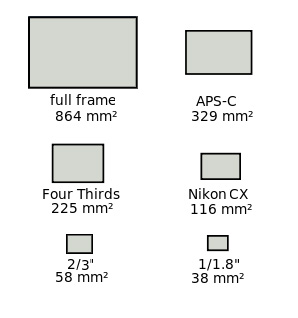

One of the most common questions our photo techs get is “What sensor size is best for me?” or some variation of that. “What does crop factor mean?” “What’s the equivalent focal length of that lens?” “Will I be able to get the look I’m going for with a smaller sensor?” And these questions totally make sense. The world of camera sensor sizes is vast and confusing. What’s worse is that the available options keep expanding. There was a time when APS-C was pretty much your only option if you wanted to purchase an interchangeable lens digital camera. Now not only are full-frame sensors available even medium format digital cameras are becoming relatively affordable. With so many available choices, and so many (often confusing and poorly defined) determining factors, how do you decide which sensor size is right for you?

The first and arguably most important factor to consider is how sensor size affects equivalent focal length. This is a somewhat confusing concept because “focal length” has, for better or worse, become interchangeable with “angle of view,” though the two terms actually mean very different things.

“Focal length,” nearly always expressed in millimeters, is the optical distance between the camera sensor or film plane and the point in the lens where light rays converge to form a sharp image. It’s not really necessary to get into too much detail about this concept here except for two crucial points:

- Focal length is constant. Regardless of the size of the camera sensor, the focal length of a lens remains the same.

- Focal length affects the angle of view, but it’s not the same as the angle of view. The angle of view is a function of both focal length and sensor size.

Canon has an online calculator that’s a pretty helpful way to illustrate this concept. Taking a 35mm lens as an example, the horizontal angle of view of a 35mm film frame will be 54.4 degrees. That same lens on a smaller format, say Super 16mm film, will only show a 20.3-degree horizontal angle of view. The lens isn’t changing, only the imaging area. Put more simply, the picture the lens is showing you isn’t changing. You’re just seeing less of it.

However, photographers and cinematographers, for the most part, don’t think in terms of angle of view. They know the concept, sure, but you’re unlikely to hear a photographer say “I want a 54.4-degree angle of view on this shot.” Instead, they’ll just say “We’ll shoot this one with a 35mm lens.” People just get used to the formats they work on and develop a sense of what they expect to see through lenses of various focal lengths. If the image format changes for whatever reason, they then need a quick way to figure out how to frame images the way they’re used to, without running to an angle of view calculator between every setup.

Here’s where the terms “equivalent focal length” and “crop factor” start to come in handy. Like “focal length” and “angle of view,” they’re related but not the same. One is used to determine the other.

Since 35mm “full-frame” film and digital sensors were the most common format among the professionals who first started having to do these calculations, that’s the default size for determining crop factor. A 35mm film frame or digital sensor has a crop factor of 1. APS-C sensors are 50% smaller than full-frame sensors, giving them a crop factor of 1.5. A micro 4/3 sensor, like the one found in the Panasonic GH5, is half the size of a full-frame sensor, so it has a crop factor of 2. These crop factors are then used to determine the equivalent focal length of a lens. Focal length multiplied by crop factor equals equivalent focal length.

For instance, If you’re used to shooting on a full-frame Canon 5D Mark IV and suddenly find yourself switching to a Panasonic GH5, you can use crop factor to quickly determine what lenses to use. Say you’re photographing a scene where you’d normally reach for a 50mm lens on the 5D. 25 multiplied by the GH5’s crop factor of 2 equals 50, so you’d want to put a 25mm lens on the GH5 to achieve the same angle of view. Remember, the true focal length of the lens never changes, only the equivalent focal length based on the angle of view you’re seeing on a particular sensor.

Sensor size also affects a number of optical qualities, some expected, some not. The foremost of these is probably resolution. Let me be clear: sensor size does NOT equal resolution, especially now. Higher resolution is easier to accomplish on a physically larger sensor area, but that doesn’t necessarily mean a camera with a larger sensor automatically has higher resolution. Plenty of APS-C cameras have higher resolution than full-frame models, for example, and just about every still camera currently available has a higher resolution than the large format Alexa 65. Very broadly, though, larger sensors tend to have higher resolution (or at least more physical capacity for resolution) than their smaller counterparts.

In fact, not only do larger sensor areas allow for more pixels, but they also allow for larger photosites (the points at which a camera sensor gathers light in order to produce an image). Given that each pixel of sensor resolution has a corresponding photosite, a 20-megapixel camera with a 35mm sensor can have larger photosites than a 20-megapixel camera with a comparatively smaller micro 4/3 sensor. Even if there’s no difference in image resolution, those larger photosites offer numerous benefits.

To greatly oversimplify it, think of a photosite as a bucket. It’s just a tiny bucket that captures light, which the camera then converts to a pixel in the captured image. The larger the bucket, the more light it can capture. Therefore, everything else being equal, a larger sensor with larger photosites will tend to work better in low light, display less sensor noise at high ISOs, and have a higher dynamic range.

This same concept works between sensors of equal sizes. Photosite size being a function of resolution and sensor size, cameras with lower resolution can accommodate larger photosites than cameras with lower resolution, even if their sensor sizes are the same. This is one of the reasons the 12-megapixel Sony A7S is more capable in low light than the 42-megapixel Sony A7R. That’s not to say that one is objectively “better” than the other. Some photographers need higher resolution and others need as little noise as possible at high ISOs. The full-frame sensor just allows the space and flexibility to choose.

Sensor size can affect depth of field as well, but, frankly, this is a very complicated issue, and one that I don’t have enough page space to dig into with sufficient detail in this article. To keep it brief, here’s what I’d say: due to a number of factors, including distance from subject and availability of lenses with wide apertures (not hypothetical equivalents), a larger sensor allows for more creative control over the depth of field in an image. This doesn’t mean that any image made with a large sensor will have a shallow depth of field or that a camera with a smaller sensor is incapable of producing images with a shallow depth of field, just that a larger sensor tends to allow more options. If this is something you’re interested in learning more about, the best explainer I could find was this article by Francois Malan at photographylife.com. It’s quite a bit longer than this entire article, so believe me when I say that it’s a difficult subject to explain concisely, but, broadly, with a larger sensor comes greater flexibility.

While this might seem like a long list of pros, it’s not as simple as “larger sensor=better.” There are also some cons that come along with full-frame and larger sensors. Primarily, bigger sensors are more expensive. So are lenses that can cover those larger sensors. Sensor and processing technology have progressed to the point where images from APS-C and micro 4/3 sensors aren’t that distinguishable from full-frame sensors. If you’re not a full-time professional (and the vast majority of the photography market isn’t), you’re probably better off spending your money on high-quality lenses over large sensors.

Camera size is another obvious benefit of working with a small sensor. Cameras with smaller sensors tend to be lighter, not just because the sensor itself is smaller, but because less space is needed for heat sinks, processors, and lens mount hardware. Corresponding lenses also tend to be smaller because they contain so much less glass. Traveling photographers might find that a smaller overall camera system is a higher priority than a huge sensor.

There are also creative benefits to working on a smaller sensor. The 2/3” sensor size and corresponding B4 lenses, for example, are popular on news and documentary cameras because, in those fields, camera size and lens reach are more important than resolution or depth of field. B4 lenses designed to cover this image format often feature focal length and aperture ranges that would be either prohibitively expensive or downright impossible in a full-frame lens.

So, like always, the answer to the question “Which sensor size is best?” is, well, “It depends.” What I can say definitively is that there have never been more options, and those options have never been better. Thanks to advances in lens and processing technology, smaller more affordable cameras like the Fuji X-T4 are 90% as effective as and 500% more portable than their full-frame competitors. Sensors small enough to fit in a drone are capable enough to shoot a feature film. The only limiting factors are cost and priorities.

Author: Ryan Hill

My name is Ryan and I am a video tech here at Lensrentals.com. In my free time, I mostly shoot documentary stuff, about food a lot of the time, as an excuse to go eat free food. If you need my qualifications, I have a B.A. in Cinema and Photography from Southern Illinois University in beautiful downtown Carbondale, Illinois.

-

Carleton Foxx