Geek Articles

Simplifying the Complexities of Lighting in Photography

As someone who teaches workshops tailored to lighting, I’m always reminded how many people have a gross misunderstanding of how light travels and is used within photography. And while I usually start my workshops with an open lesson on the reality of how light functions. I’m frequently reminded, how, even the most experienced photographers, don’t have an accurate understanding of light and it’s fall off properties.

So I figured, if Roger is on this blog, taking apart lenses, debunking myths about filters, and showing uber nerdy MTF charts of the latest lenses, then I can show some of my expertise on lighting as well. And as always, I want to start with the Inverse Square Law.

Inverse Square Law

The Inverse Square Law is a pretty fundamental part of using lights within photography. If you plan on shooting anything other than natural light, I consider this rule to be a fundamental ‘must know’ law in photography. The Inverse Square Law, in mathematical terms, is broken down as follows —

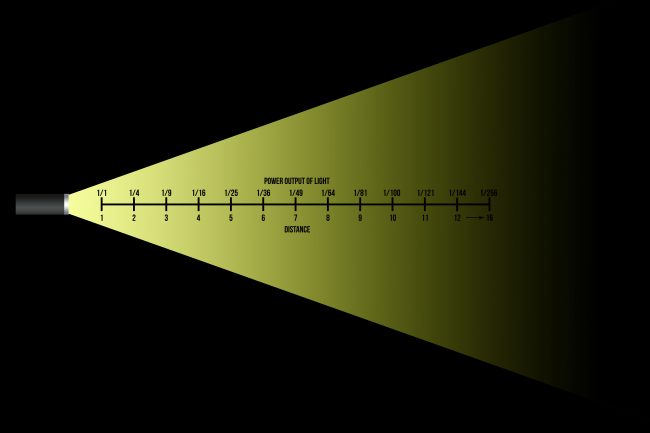

In English, this translates to ‘Intensity is proportional to 1 divided by distance squared.’ And while I don’t expect all the readers to see a math equation and immediately understand what it means, it can be broken down into pretty simple terms. All you need to know in reference to the inverse square law is that it measures the falloff of light over distance. To put it simply, each time you double the distance of your light to your subject, you lose 3/4th or 75% of your output of light. This seems complicated, as most people assume that doubling the distance would lose half the power, but no one said that lighting was easy. Double the distance, lose 3/4th of the power.

What this means, is that you don’t need nearly as much power as you think you do, and that distance is far more important than power. For example, a strobe like the AlienBees B800 is a standard light for many portrait photographers, and usually, has enough power to be able to shoot on location. At 320Ws, people consider this strobe to have plenty of power. But the inverse square law tells us the power has a greater falloff with distance, so if it’s 320Ws at 1 meter from your subject, it’s only putting out an equivalent of 12.8W at 5 meters away.

The fall off is more extreme at the shorter end of the spectrum (the power change from one meter to 4 meters (from 320Ws to 20Ws) is more significant than the power shift from 10 meters to 20 meters (3.2Ws to .8Ws), so the secret to lighting is that distance is everything. If you want your light to illuminate your subject, without having drastic effects on your background, bring your light as close as possible to your subject.

The Power Output Reality

The most common misconception when it comes to lighting is that the standard unit of measurement means something in regards to light output. Most lights are measured in Watt Seconds, which has foolishly became the standard for lighting gear within photography. Much like how speaker size doesn’t measure decibel rating in music equipment, Watt seconds doesn’t give an accurate reading of how much lumens each light is creating. In short, Watts is a measure of the electrical power the light itself draws, and so watt second is how much power it draws in a given second. Surely you’ve seen this if you’ve ever swapped out one of your traditional incandescent light bulbs for a LED bulb. While the wattage used is much less, the actual light output (generally measured in lumens) is the same. A photography strobe’s actual power output is going to come down to a number of different reasons. And while Watt seconds is the universal term to describe light output, we’re developing a way to better deduct how much output each light is capable of generating (stay tuned).

But continuing on that trend, many people don’t even understand the power rating scale on their own lights. Using the Profoto B1 as an example – with a power scale going from 1-10, with 10 being the highest setting, where do you suspect half power to fall on the dial? Many assume 5, but the reality is that half power, or 250Ws, is actually 9. The same applies to AlienBees and just about every other major strobe manufacturer on the market, and relates back to the inverse square law and how light intensity is inversely proportional to distance. So 500Ws is only 1 stop more powerful than 250Ws, and 1000Ws is only one stop above 500Ws. Understanding this, along with the Inverse Square Law gives you a better understanding of the capabilities of your lights, and their output. Generally speaking, one of the biggest advantages of the large and cumbersome ProPacks is that they have output ratings of 2,400Ws and above, allowing you to better take advantage of a space, and spread out for your shoot.

Softness and Size Relativity

Another thing worth discussing is the extreme diversity of a single lighting modifier and how it corresponds to softness and hardness of light. Without question, my favorite modifier is my 2’x3′ Softbox, because it is considered medium by just about all standards, giving it an immense amount of flexibility. By adjusting its angular size, you’re able to get a broad range being hard light and soft light.

In simple terms, angular size is based purely on the perspective of the subject. When you have a 2’x3′ softbox a foot from your subject, the light itself appears massive from their perspective, obstructing much of their view. Because the light looks large based on their perspective, it’s going to create softer light naturally. The smaller the light source, according to their perspective, the harder the light is.

And there is no better evidence of this than our own Sun. The diameter of the sun is 864,576 miles – quite obviously the largest light you will ever have access to. But because the sun nearly 93 million miles away from Earth, it appears small from our perspective (Just trust me, don’t go out and stare at the sun). That gives the sun incredibly hard lighting – harder than pretty much any other light source available to you. While obviously bare lights can still produce extremely hard and dramatic shadows and highlights, it cannot fully replicate the harshness of the sun on a cloudless day. This evidence can be seen by standing outside with a grid on a sunny day. Notice how the grid displays its pattern correctly on the ground below? Simply put, you cannot do that with a traditional strobe – without the use of some specialized tools.

One of those tools comes in the form of something called a Hardbox. To my knowledge, Profoto is the only manufacturer who makes a Hardbox, but how it works is pretty simple. By seating the light within the modifier at an off angle, you’re able to drastically cut the size of the light source down, to better mimic the sun. This allows you to get the hardness of light found from the sun while maintaining control over your angle and power. Though this is just an example to show that your bare strobe isn’t the hardest light obtainable, as we don’t generally rent out speciality items like the Hardbox.

So gaining full control over your lighting comes in with an understanding of both the inverse square law, as well as angular size relativity of your lights. Learning those two principles allows you better control of the softness and hardness of your lights and modifiers, as well as a better understanding of the power output of your lights and how they affect your scene and subject.

While I don’t expect you to remember every single one of the figures and facts I’ve presented here in this article, I do hope that you’ve learned something, and are better aware of how light functions when using it within photography. Like all things photography, you can nerd out and talk figures all day long, but to fully get an understanding of the principles taught, it’s best to get out there and practice them. We have a broad range of lighting equipment for both photography and videography, so give us a call and we can help you find which tool might be best for you.

Author: Zach Sutton

I’m Zach and I’m the editor and a frequent writer here at Lensrentals.com. I’m also a commercial beauty photographer in Los Angeles, CA, and offer educational workshops on photography and lighting all over North America.

-

Petrochemist

-

Douglas Dubler

-

Luigi Gallerani

-

Peter

-

Ian Goss

-

decentrist

-

Ian Goss

-

Sator Photo

-

SpecialMan

-

Zach Sutton Photography

-

SpecialMan

-

Max Dallas

-

Jeremy Mills

-

Athanasius Kirchner

-

Graham Stretch

-

Haywood Jablome

-

Rupert

-

Zach Sutton Photography

-

Athanasius Kirchner

-

Zach Sutton Photography

-

Mike Carnevale