Geek Articles

How Image Stabilization Works In Camera and In Lens

Image Stabilization comes in a variety of different names and types. Whether it’s called O.I.S. (Optical Image Stabilization), VC (Vibration Compensation), VR (Vibration Reduction), IBIS (In-Body Image Stabilization) or just IS (Image Stabilization), it all foundationally does the same thing – controls the effects of camera shake to produce sharper images. With the recent years, In-Body Image Stabilization has been created, and the bulk majority of the latest lens releases from Canon and Nikon come with some iteration of image stabilization. But what does all this mean, and how does image stabilization fundamentally work?

Why You Might Need Image Stabilization

Within your first year in photography, you’re likely going to learn a foundation rule of photography; while handholding, to avoid blurry images from camera shake, your shutter speed shouldn’t be slower than your focal length. So if you’re shooting with a 50mm lens, you’ll want to shoot at least 1/50th of a second to avoid camera shake. 200mm lenses should be shot at 1/200th of a second or higher, 400mm lenses at 1/400th and so on.

However, this rule changes entirely once you add Image Stabilization systems into the mix. Most modern IS systems offer 3-5 stops of image stabilization, meaning where you once were theoretically limited to 1/200th of a second on a 200mm focal length lens, you can now shoot the same images at 1/13th of a second (4-stops of exposure). This has enormous advantages, especially when working handheld or with limited available light, which is why every camera and lens developer is working to extend image stabilization to 6 stops and beyond.

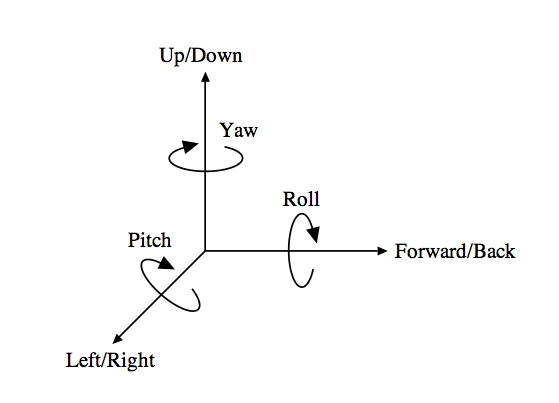

Because cameras are a three-dimensional tool, image stabilization systems need to work on up to six different planes to properly correct camera movement. The most simple camera shake will be directional shake; horizontal, vertical and forward/back shakes. Rotational shake, or commonly referred to as pitch and yaw, control the horizontal and vertical rotational movements that can occur while handholding.

How Lens Image Stabilization Works

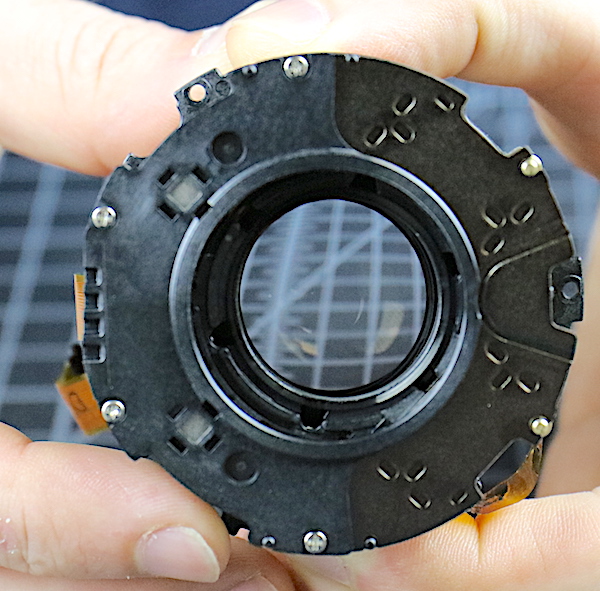

By default, image stabilization comes in two different flavors – in lens stabilization or in-camera body stabilization. These two platforms work differently, but work to produce similar results. To put it simply, in lens stabilization has a floating lens element which is controlled electronically by a microcomputer and shifts in the opposite direction of the camera shake, helping to stabilize the image. All of this is detected in mere microseconds and can give you up to 5-stops of stabilization, depending on the lens, movement, and focal length. Below is a short diagram showing you how this works to help counteract any camera shake.

In-lens image stabilization is by far the most common type of stabilization system. However, there is another type of image stabilization system that is becoming more and more popular, commonly called In-Body Image Stabilization (IBIS).

How In-Camera Stabilization Works

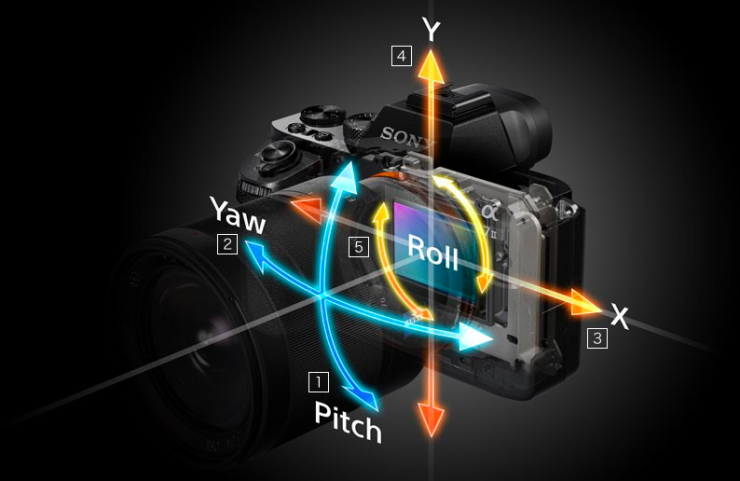

In recent years, through the help of Sony and Fuji cameras, In-Body Image Stabilization has become more and more common in cameras. Whereas image stabilization within the lens has a floating lens element helping to counteract the camera’s movement and shake, In-Body Image Stabilization has a floating sensor that helps neutralize any movement within the camera. The key advantage to this system is that if your camera has IBIS, all of the lenses you use with it will also have image stabilization.

Is In-Lens or In-Body Stabilization Better?

A common call we get here at Lensrentals.com is the cut to the chase “Which is better?”. But it’s not as simple as that, as both systems have advantages and disadvantages. For example, in-lens stabilization will generally perform better on longer focal lengths, because camera shake requires more compensation at the pivot point (camera) than it does within the lens. This is why many Sony telephotos still have in-lens stabilization, despite having IBIS on all of their mirrorless systems. So let’s look through some advantages of each system, to determine what works best for you.

Advantages to In-Lens Stabilization

- It’s far more effective in telephoto lenses. A subtle shake of the camera is pretty drastic when shooting at 500mm, and will naturally be better compensated within the lens rather than the camera body.

- Lens stabilization works better in low light conditions. Because the IS is working as an independent unit, you’ll have better results with in-lens stabilization while in low light conditions. In-Body Image Stabilization will often have trouble metering and focusing in lower light situations while activated.

- By in large, In-Lens Stabilization is more effective. While many camera companies developing IBIS will deny this, generally in-lens stabilization will provide better results. This is because the image stabilization is fine-tuned for each lens, and usually offers multiple IS modes depending on the situation. However, with systems like the Sony a7rIII and Sony a7III offering 5 stops of image stabilization, this argument is slowly fading away.

- Has no effect on your metering and autofocus. Unlike with IBIS, in-lens IS will have no negative effects to your autofocusing and metering while activated.

- By design, In-Lens Stabilization will offer better battery life. In-lens stabilization requires smaller motors to move the optics for camera shake, and is far less draining on the battery when compared to in-body image stabilization.

Advantages to In-Body Stabilization

- Generally, In-Body Image Stabilization (IBIS) is cheaper in the long run. While IBIS will usually be an added cost to the camera body purchase, it is a one time purchase and will usually result in lower lens prices, when compared to similar lenses with IS built in.

- In-Body Stabilization is universal – and works with all lenses. To further the point above, once you have IBIS, you should be able to use image stabilization with all the lenses in your kit.

- Unlike with most lenses with IS built in, IBIS operates in silence. If you’ve activated image stabilization on a lens, you’ve likely heard clicking and other noises from the lens while focusing. That is (usually at least), the image stabilization system making adjustments.

- IBIS offers cleaner bokeh when engaged. With IS turned on for in-lens systems, you’re asking the lens to make optical adjustments to counteract any movement, which can result in some weird bokeh. Because the optics are stationary with IBIS system, you will get a cleaner bokeh.

Misconceptions Regarding Image Stabilization

There are a few misconceptions with image stabilization systems that we need to answer often through tech support calls. So let’s go over a few of them here.

Can you use both in-lens stabilization and IBIS?

In short, yes. While it is dependent on the camera system you’re using (for example, Panasonic has a list of compatible lenses), but you should be able to use them together. With Sony systems, activating both systems will delegate 3-axis stabilization to the IBIS, and leave the pitch/yaw adjustments for the Optical Steady Shot (O.S.S) in-lens stabilization. Fuji systems, at least the Fujifilm X-H1, work in a similar fashion; delegating specific axis’ to different systems to achieve the standard 5-axis stabilization.

Should I turn off IS before demounting a lens?

As a general practice, yes. If you have Image Stabilization activated on a lens, you’ll want to turn it off, wait three seconds, and then unmount the lens. Not doing this can potentially put the IS system in what we call an ‘unparked’ position, which means the optics are still floating, which could cause damage if shaken and jarred.

Is there a theoretical limit to image stabilization?

Olympus seems to think the limit is 6.5 stops of image stabilization. In a recent interview, Setsuya Kataoka, part of the Imaging Product Development Division at Olympus, claimed that image stabilization’s theoretical limit is set at 6.5 stops of stabilization, due to rotation of the earth interfering with gyro sensors. I’ll let the comments below determine if that is a scientific fact, or just marketing mumbo jumbo.

Does image stabilization help with fast moving subjects?

No. Image stabilization is designed to control only the movements from camera shake. It won’t help stabilize any blur caused by moving subjects.

The Naming Schemes of Various Image Stabilization Systems

Likely because of patents, each brand has their own naming for their image stabilization, which is why most modern camera lenses have half a dozen letters slapped to the end of their official product name. So here is a quick reference guide for what each major brand calls their image stabilization system.

| Lens Brand | Image Stabilization Name |

| Canon | IS (Image Stabilization) |

| Nikon | VR (Vibration Reduction) |

| Sony | O.S.S. (Optical Steady Shot) |

| Panasonic | Mega O.I.S. (Mega Optical Image Stabilization) Power O.I.S. (Power Optical Image Stabilization) Dual I.S. (Dual Image Stabilization) |

| Sigma | OS (Optical Stabilizer) |

| Tamron | VC (Vibration Compensation) |

| FujiFilm | OIS (Optical Image Stabilization) |

| Olympus | IS (Image Stabilization) |

Hopefully, we were able to help with any questions you may have had regarding image stabilization, and if you have additional questions, feel free to chime in in the comments below or give us a call.

Author: Zach Sutton

I’m Zach and I’m the editor and a frequent writer here at Lensrentals.com. I’m also a commercial beauty photographer in Los Angeles, CA, and offer educational workshops on photography and lighting all over North America.

-

Driek Berndsen

-

Driek Berndsen

-

Shelby Deeley

-

Michael Clark

-

Michael Clark

-

Michael Clark

-

Jan Steinman

-

Athanasius Kirchner